Laid bare: The playful side of Robert Mapplethorpe

22 November 2016

Fearless and provocative, Robert Mapplethorpe is best known for his frank photos from New York’s vibrant and diverse gay scene. To mark what would have been his 70th birthday, a new exhibition shows a lesser-seen, more playful side of the artist’s work. WILLIAM COOK pays a visit.

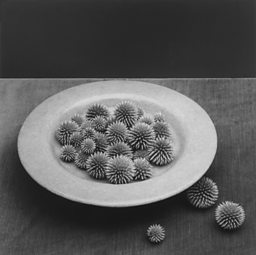

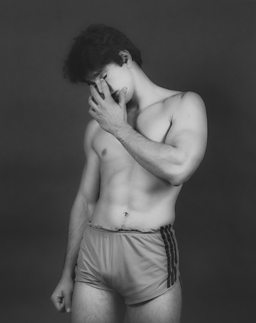

In the sleek white atrium of London’s Alison Jacques Gallery, there are two contrasting pictures which sum up Robert Mapplethorpe’s strange allure. One is a huge photo of a young man in a state of sexual arousal. The other is a small photo of frogs scampering across a plate.

Oddly, it’s the smaller photo which seems more shocking, more disturbing. Mapplethorpe had a talent for making even the most extreme sexual practices seem humdrum. It’s when his models put their clothes back on that things get really weird.

His models were his friends and lovers. Photography was his autobiography - he was a participant, not a voyeur

Mapplethorpe died of an AIDS-related illness in 1989, aged just 42, but after all these years his fame – and infamy – shows no sign of fading. There have been retrospectives of his work this year in Paris, Oslo and Los Angeles. There are shows running in Turin, Stockholm and Montreal.

So what is it about Mapplethorpe which transfixes us? What is it about his pictures which continues to command our gaze?

Mapplethorpe made his name with his graphic depictions of New York’s Gay community, specifically the leather bars which occupied a secret corner of that scene. His bold studies of butch macho men were revolutionary. No one had portrayed this subculture so candidly before. American was scandalised, and his celebrity (and notoriety) was assured.

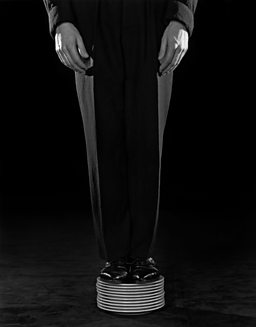

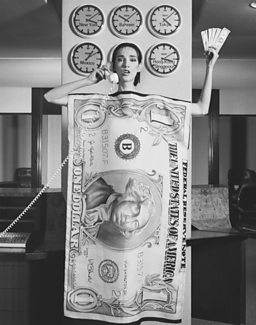

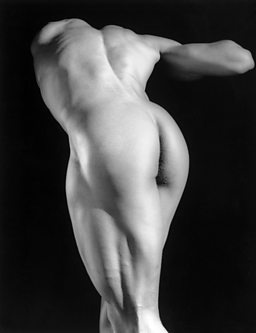

Yet there was more to his art than shock and awe, or S&M. He was a perceptive portraitist with a classical flair for composition. Whether he was shooting a still life or an erect penis, he found theatricality in every scene.

“Really, what he was interested in was sculpture,” says Alison Jacques. “There’s something about the way he looks at things which is utterly unique.”

The thing that gave Mapplethorpe’s art such power was that he lived the life he photographed. His models were his friends and lovers. Photography was his autobiography – he was a participant, not a voyeur.

“Whenever you make love with someone there should be three people involved – you, the other person and the Devil,” he said. The same could be said of his portraits. There was a ruthlessness about his work, an indifference to the human cost which resembled the amorality of a sexual predator.

“When I have sex with someone I forget who I am,” he said. “It’s the same thing when I’m behind a camera.” No wonder Derek Jarman likened him to Faust.

The artist he most resembles is Caravaggio: the same understanding of lust and savagery

Yet the defining feature of his art isn’t brutality but beauty, and this is what comes across in this new show. He could be cruel, but he was never cold, like Warhol. The artist he most resembles is Caravaggio: the same understanding of lust and savagery; the same contrast between light and shade.

Despite his hip subjects, his pictures are actually quite traditional. Like Caravaggio, his work is imbued with a Catholic sense of sin.

Alison Jacques has staged half a dozen Mapplethorpe shows during the last decade. This time, she’s asked German photographer Juergen Teller to curate a selection of Mapplethorpe’s work. Teller discovered Mapplethorpe as a teenager, when he bought Patti Smith’s Horses LP, and saw Mapplethorpe’s iconic portrait on the cover.

He had no idea who Mapplethorpe was, or that Smith and Mapplethorpe were close friends. As he found out more about Mapplethorpe, he grew to like him more and more. He was attracted by his directness, his selfishness.

“Some people see him as a crude, narcissistic, harsh photographer,” says Teller, ”but I think he has a lot of warmth.”

Teller owns one of Mapplethorpe’s most famous photos, Man in a Polyester Suit, but his selection for this show ignores the greatest hits. Rather than the wilting flowers and the demonic self-portraits, he’s chosen a range of less familiar images – more intimate, more playful.

Even if you’re a Mapplethorpe fan, there’ll be many pictures in this exhibition you’ve never seen before.

“I wanted to show a gentler, more romantic side,” says Teller. “People say he’s extremely serious, but I found a little bit of humour in it, too.”

It’s important to point out that this is not a show for all the family. Some of these shots are incredibly explicit. You wouldn’t want to bring your children here, or probably your parents either.

Sex was only part of Mapplethorpe’s oeuvre, but even his pictures of objets d’art have a powerful sexual charge.

His unflinching photos took Gay culture out of the ghetto and into the gallery

“Sex is magic if you channel it right - there’s more energy in sex than there is in art,” he said. He channelled his sex drive into his art and the effect is extremely potent, even when the subject matter seems tame.

“Sex is the only thing worth living for,” declared Mapplethorpe. What a sad and spiteful irony that he died from a sexually transmitted disease.

This show marks what would have been his 70th birthday. We can only guess at what else he might have achieved. What would he make of today’s sexualised mass media? By comparison, his raw Polaroids seem almost naïve.

When Mapplethorpe started out, homosexuality was still widely regarded as a psychiatric disorder. His unflinching photos took Gay culture out of the ghetto and into the gallery, but his legacy isn’t confined to homosexuality, or photography.

Today Mapplethorpe’s influence is everywhere, from fine art to advertising. His groundbreaking work has become mainstream. Yet although he’s influenced countless photographers, none of his imitators has ever quite matched him.

It’s like watching Reservoir Dogs or listening to Never Mind the Bollocks. When you come face to face with his hypnotic pictures, you know this is the real thing.

“He broke a lot of boundaries,” says Alison. “He said his own thing in his own way – and it’s unmistakably him.”

Teller on Mapplethorpe is at the Alison Jacques Gallery, London, from 18 November 2016 to 7 January 2017.

Related Links

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms

More photography from BBC Arts

-

![]()

War and peace

The compassionate photography of Don McCullin.

-

![]()

Childhood in the 1970s

Tish Murtha’s tender photos of deprivation in Britain.

-

![]()

Neon dreamland

Liam Wong's sci-fi-style images of Tokyo at night.

-

![]()

Pup art

William Wegman's Polaroids of his loyal Weimaraners.

-

![]()

Stanley Kubrick

1940s New York through the lens of teenage Stanley Kubrick.

-

![]()

Jailhouse Rock

Behind-the-scenes photos of Johnny Cash's prison shows.

-

![]()

The real Sin City

Hard-boiled photographs tell the history of crime in LA.

-

![]()

10 years with Kate Bush

Rare photographs of the singer at the height of her career.