Five books that could change your life

What was the book that first made you stop – think – wonder – and start to live your life just a little bit differently? Many of us have one, whether it's a favourite novel, a thought-provoking autobiography or a collection of poems that adjusts your filter on the world. The Essay asked five leading figures in the media and arts to share the books that changed their lives: here's what they said.

The book that forced me to grow up

The Wire’s David Simon on Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941) by James Agee

David Simon is the creator of TV series the Wire. An aspiring journalist since childhood, he grew up looking forward to being part of a world of cynical, wise-cracking newpapermen. As a young reporter, he revelled in a healthy contempt for authority and by the age of 24 thought he “had the whole world by the ass”.

Reading it made me grow up – more honestly, perhaps, it demanded that I begin to grow up.

It was then that an older journalist handed him a dog-eared old paperback – James Agee’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Simon was intially scornful of the title. He had no interest in pandering to celebrity. But when he finally read the book, he was surprised to find a “gentle masterpiece of reporting”.

Agee’s work, which grew out of a commission by Fortune magazine, examines the lives of desperately poor sharecropping families in the Deep South during the Depression. Simon, a brash young hack sitting on the rewrite desk of the Baltimore Sun, found himself shamed by the writer’s careful, precise and compassionate approach to his subjects, the love he felt for these human beings in the balance. “It made me ashamed and proud to be a journalist, all in the same moment,” he says. Listen now.

The book that helped me find my inner voice

Singer Pauline Black on To Kill a Mockingbird (1960) by Harper Lee

“Whoever said ‘little girls should be seen and not heard’ obviously hadn’t read To Kill a Mockingbird.” In 1966, singer Pauline Black was 13 and the only biracial child in an all-white school in Romford. It was a confusing, frustrating childhood: the adopted child of white parents, she was part of a loving family who professed their affection but at times used racist language and muttered about being “swamped” by dark-skinned immigrants.

For Black (then finding distressing reference points to black identity in news coverage of American riots), it was Harper Lee’s coming-of-age novel To Kill A Mockingbird that finally “provided a torch to shine into those dark secret places where humanity hid its hypocrisy”. She found herself identifying with several of the characters, from the tomboyish protagonist Scout to the profoundly lonely Mayella Ewell.

The novel’s black characters captivated her, too: for the first time she saw black characters endowed with a “dignity and gravitas” she had never seen before. It also provided “much-needed” insight into what it meant to be a mixed race child.

Yet it was the book’s central motif, the sweet-singing mockingbird, that made the greatest impression. "Singing my heart out is what I’ve been doing for most of my life," she says.

“This novel gave the little black girl that timidly lingered inside me the security to come out and fight against racial injustice with music.” Listen now.

The book that revealed my path in life

Vice News’s Ben Anderson on Autobiography of Malcolm X (1965) by Malcolm X and Alex Haley

As a teenager in Bedford, Anderson was drawn to the “bold and brash energy” of American culture. Immersing himself in US popular culture, he learned for the first time about the civil rights struggle and listened to music by Henry Rollins, Public Enemy and NWA – admiring the way that they demanded, rather than asked for, a better life.

While he initially admired Martin Luther King's ideas of non-violence, it was ultimately the militancy of rappers like Public Enemy that he found more attractive. It was in their music that he first heard samples of the “calm but fiery” Malcolm X, spokesman for the Nation of Islam. The latter’s autobiography, co-written with Alex Haley between 1963 and 1965, proved revelatory: "Suddenly a fire was lit inside me. I had a path to follow," he says.

Malcolm X's urge to see the world for himself became a source of inspiration that would inform Anderson’s decision to become a journalist. "This basic approach of just getting there and witnessing has become my job," he says.

"Malcolm X's constant search, his relentless curiosity, his willingness to face unpleasant facts and reinvent himself, set an example that I’ve tried to follow ever since." Listen now.

The book that made me an artist

Artist Tacita Dean on Fires (1936) by Marguerite Yourcenar

Tacita Dean discovered Marguerite Yourcenar’s collection of prose poems as a student while browsing in a bookshop. Suffering at the time from a broken heart, she found solace in this book (itself the “product of a love crisis”) and its heartfelt, sometimes somewhat melodramatic sentiments – so melodramatic, in fact, that the grown-up artist is slightly embarrassed to read them!

She gave a female voice to my passionate and romantic younger self who was trying to find an artistic context for the desire I had to reach out and touch the classical past.

Nevertheless Fires, with its "pithy and uncompromising" language, had a deep impact on Dean and her work as a young artist. Her love of Greek culture was reflected in Yourcenar’s depictions of the poetry and the “visceral horror” of the classical past. Equally attractive was the book’s overarching sense of dark, female personality. This was the late 1980s: Dean was discovering feminism, and Fires’ strong female characters, all utterly complicit in their own fates, resonate strongly with ideas around female equality.

Also growing was Dean's interest in film – and Fires is “pure cinema”. Listen now.

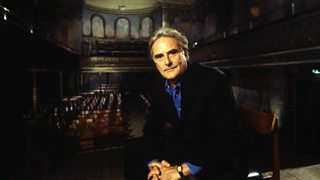

The book that taught me to take nothing for granted

Director Sir Richard Eyre on The People's War (1969) by Angus Calder

It was far from home and in the pages of this book that Richard Eyre found himself learning for the first time about a faraway country of which he knew very little: his own.

Angus Calder’s social history of World War Two relives the experience of ordinary citizens during the conflict: their “endurance and patience, their cowardice, complaints, and selfishness, as much as their heroism and humanity”. It was a world that Sir Richard, born in 1943, had technically experienced first-hand as a child. Yet reading Calder's account of those turbulent years changed his thinking.

“It provided me with a way of thinking about the world in which I grew up,” he says. “It gave me hope that change had been possible in my immediate past, and further change could – and would – take place in my immediate future. I was wrong, of course.” Nevertheless, Calder's history provided a vision of social justice that was in sight during the social revolution of wartime.

"It’s the only book I return to constantly and obsessively – for solace." Listen now.

The Essay: The Book That Changed Me is online now at the Radio 3 website. You can also download it for 30 days via BBC iPlayer Radio.

-

![]()

The Book That Changed Me

Famous figures discuss the books that changed their lives.

-

![]()

Coming up roses: the meaning of flowers

Seven charming facts we learned about roses... and romance.

-

![]()

The Essay

Leading writers on arts, history, philosophy, science, religion and beyond.