There are already three women in the room when the Taylors arrive. Jim Taylor heads to the opposite corner from where the trio is seated. His grown-up daughter, Denise, follows him. The two groups eye each other uncomfortably. This is the room that you wait in before attending a parole board hearing where they decide whether a prisoner should be released.

Neither the women nor the Taylors are used to seeing other people here, at the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, California. They are unsure if they are there in opposition to each other. They don’t talk, but they listen. After a few minutes they realise that they are all victims of a crime, and that they are attending different parole hearings. One of the women turns to the Taylors, a look of relief on her face. “You’re not the enemy,” she says. “I’m not the enemy to anybody, not even the defendant,” Jim replies.

The women look at each other. They weren’t expecting that. In their world, defendants are always the enemy and victims attend parole hearings for one reason – to make sure the enemy doesn’t get out. They try again. This time a different woman asks Jim how long he has been coming here. “Twelve years,” he says.

He keeps talking. One day, he says, he hopes to visit the defendant outside prison. That is not what the women want for the defendant whose parole hearing they are there to attend. When a prosecutor informs them that their inmate’s parole will hopefully be denied, they nod in agreement. “Hopefully,” they say. Jim looks at his daughter, Denise. “Situation’s different,” he says.

She is the reason they are there, Denise and her brother, Bo. But Bo is dead. Ronnie Fields, the man whose parole they are there to support, murdered him.

He doesn’t look at them. He is dressed in what look like blue hospital scrubs. He has a beard and black glasses: Ronald Fields, inmate D00742. The Taylors call him Ronnie. Rules dictate that Fields should not look at the Taylors unless given permission to do so.

The Taylors have left the waiting room and are now across the hall in Conference Room Two. The prosecuting attorney doesn’t talk to the Taylors and he doesn’t make room for them next to him at the table.

They find seats against the wall with the victim’s advocate, a large woman with an abundance of purple hair. Fields sits at the table, next to his state-appointed attorney, DeJon Ramone Lewis, the same lawyer who represented Charles Manson at Manson’s parole hearing in 2012.

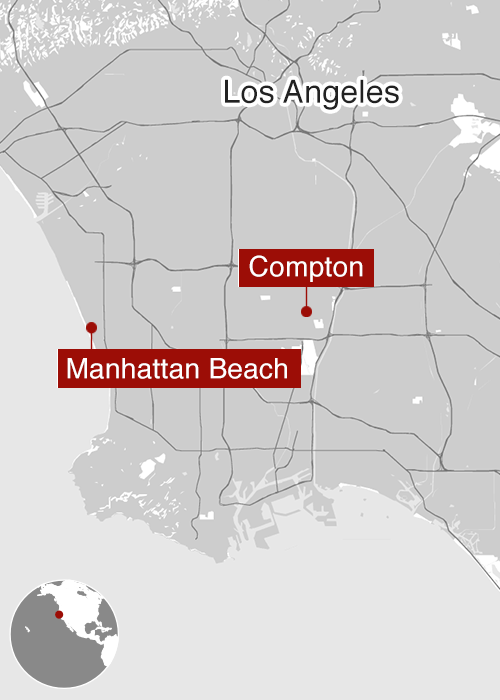

It is just after 08:30 in the morning on 6 December 2016 when commissioner Jack Garner begins introductions. He warns the Taylors that the documents he will be reading from may be graphic and difficult for them to hear. They know. They have heard the story before. It starts on a September afternoon in 1984 with Bo and a friend trying to buy marijuana in Compton, a city in Los Angeles County synonymous with gang violence. It ends with Bo being shot.

There are more details in the court documents: the location of the liquor store where Bo and his friend found Fields’s friend smoking a joint, the different places Fields took them to purchase pot, the type of car Fields was driving, the name of the street Bo was killed on.

The only detail that really matters though is that after deciding to take Bo’s money without handing over the drugs, Fields took a home-made gun from his car. He told Bo and Bo’s friend to run.

Bo, confused, asked: “What?”

There was a single shot. It struck Bo in the heart. Fields was sentenced to a minimum of 27 years.

Thirty-two years later Bo’s father makes his way to one of the room’s many microphones. He is here to voice his support for Field’s release, something only about 1% of victims’ families do, according to commissioner Garner. Jim shuffles the way old men do, stumbling slightly. He is 78 now, with white hair and a bit of a belly. He has a tendency to ramble. It doesn’t take long for him to deviate from the statement his daughter helped him prepare. He mentions Fields’s father and then how much Fields has changed over the years.

“I don’t know how he could show any more remorse than he has,” Jim says, his voice cracking. “Certainly, I’m satisfied.”

Denise hands her father a tissue. Then she replaces him at the table and reads her own statement. She is 54 and has lived most of her life without her brother, her only full biological sibling.

Her father removes his glasses and wipes his eyes. Denise stops for a minute, unable to continue. Then starts again:

Having to come back to these parole hearings year after year only causes more pain to me and my family.”

“I realise that Mr Fields’s crime is considered to be against the state, but we are the ones who live the day-to-day reality of the loss of my brother, Bo. And also the continued imprisonment of the man responsible for his death, a sentence that we no longer support.”

Denise makes her way back to her seat. Jim puts his arm around his daughter’s shoulders. He pats her back. She says:

I get more emotional each time. I never cried in the first hearing.”

Fields’s gaze remains fixed straight ahead, his face a mask.

The Taylors have left the waiting room and are now across the hall in Conference Room Two. The prosecuting attorney doesn’t talk to the Taylors and he doesn’t make room for them next to him at the table.

They find seats against the wall with the victim’s advocate, a large woman with an abundance of purple hair. Fields sits at the table, next to his state-appointed attorney, DeJon Ramone Lewis, the same lawyer who represented Charles Manson at Manson’s parole hearing in 2012.

It is just after 08:30 in the morning on 6 December 2016 when commissioner Jack Garner begins introductions. He warns the Taylors that the documents he will be reading from may be graphic and difficult for them to hear. They know. They have heard the story before. It starts on a September afternoon in 1984 with Bo and a friend trying to buy marijuana in Compton, a city in Los Angeles County synonymous with gang violence. It ends with Bo being shot.

There are more details in the court documents: the location of the liquor store where Bo and his friend found Fields’s friend smoking a joint, the different places Fields took them to purchase pot, the type of car Fields was driving, the name of the street Bo was killed on.

The only detail that really matters though is that after deciding to take Bo’s money without handing over the drugs, Fields took a home-made gun from his car. He told Bo and Bo’s friend to run.

Bo, confused, asked: “What?”

There was a single shot. It struck Bo in the heart. Fields was sentenced to a minimum of 27 years.

Thirty-two years later Bo’s father makes his way to one of the room’s many microphones. He is here to voice his support for Field’s release, something only about 1% of victims’ families do, according to commissioner Garner. Jim shuffles the way old men do, stumbling slightly. He is 78 now, with white hair and a bit of a belly. He has a tendency to ramble. It doesn’t take long for him to deviate from the statement his daughter helped him prepare. He mentions Fields’s father and then how much Fields has changed over the years.

“I don’t know how he could show any more remorse than he has,” Jim says, his voice cracking. “Certainly, I’m satisfied.”

Denise hands her father a tissue. Then she replaces him at the table and reads her own statement. She is 54 and has lived most of her life without her brother, her only full biological sibling.

Her father removes his glasses and wipes his eyes. Denise stops for a minute, unable to continue. Then starts again:

Having to come back to these parole hearings year after year only causes more pain to me and my family.”

“I realise that Mr Fields’s crime is considered to be against the state, but we are the ones who live the day-to-day reality of the loss of my brother, Bo. And also the continued imprisonment of the man responsible for his death, a sentence that we no longer support.”

Denise makes her way back to her seat. Jim puts his arm around his daughter’s shoulders. He pats her back. She says:

I get more emotional each time. I never cried in the first hearing.”

Fields’s gaze remains fixed straight ahead, his face a mask.

It was the year they were supposed to become friends. That is what Denise hoped. It was 1984 and she was back home in Manhattan Beach, outside Los Angeles, a 22-year-old college graduate. She was going to work and apply to medical school while living at home. She would have time on her hands, time she wanted to use to get to know her little brother better. Bo was an adult now, 19.

Denise thought if she made the effort they could be friends, just like her father and his sister were.

As children, Denise and Bo had never really got along. Denise was the “good kid”. She did well in school, stayed out of trouble and listened to her parents. Back when they had a shared bedroom, her side was always neat and orderly. Bo’s side was pure chaos. His report cards were never good. He was always finding ways to get out of class, getting in trouble. He was like that even before their parents divorced, but Denise thinks the divorce made things worse. It happened when she was about 13 and it split the siblings apart, Bo went with their father and Denise went with their mother. Denise felt lucky. She remembers her father as angry.

Jim admits he has had to work to become the person he is today, hinting at earlier struggles. He completed a 12-step addiction programme before he got what he describes as a second chance at life.

He comes from a very conservative religious background. He remembers thinking people in his church, the Church of Christ, were good, but outsiders – Pentecostals, Baptists – were bad. It was a narrow tunnel vision it took him years to shed, one that his children followed when they were young. Denise told her grade school friends that she wished they would go to church because she was sad they were going to go to hell.

Although he has softened over the years and discarded some of his earlier hard-line viewpoints, Jim still teases Denise for being too liberal. He questions whether Bo would have changed, whether Bo would have used the potential he believes he wasted:

I always wondered what Bo would be. He was a troubled child. But I’ve seen others turn their lives around.”

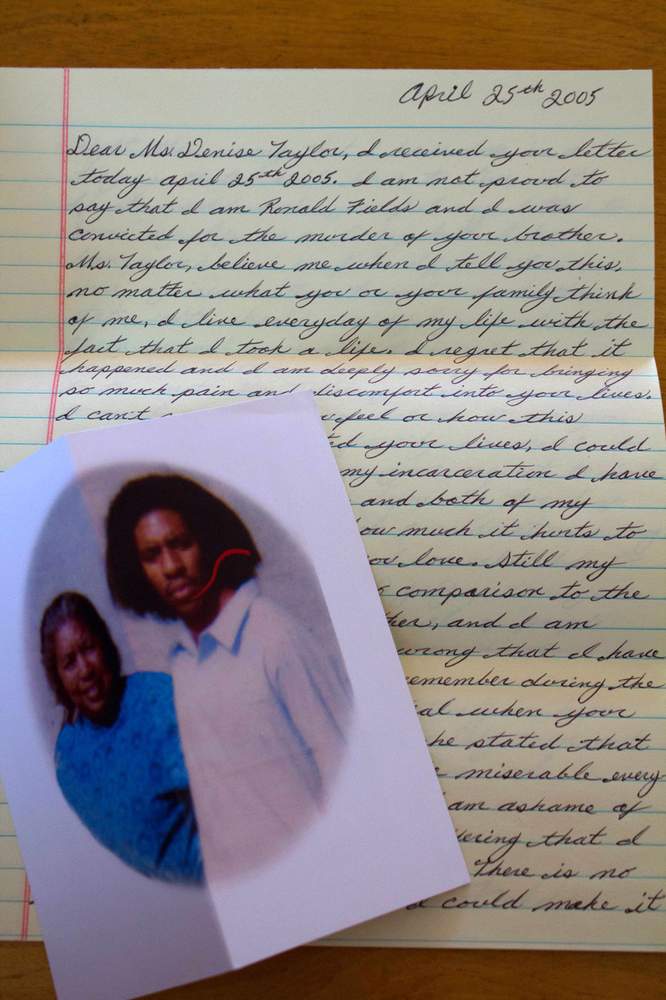

No-one seems to remember whether Bo graduated from high school. Denise recalls him being into gardening. Both she and her father remember him hanging out at the beach, his hair blond and tousled, his chest bare, just like it was the day he was shot.

It was the year they were supposed to become friends. That is what Denise hoped. It was 1984 and she was back home in Manhattan Beach, outside Los Angeles, a 22-year-old college graduate. She was going to work and apply to medical school while living at home. She would have time on her hands, time she wanted to use to get to know her little brother better. Bo was an adult now, 19.

Denise thought if she made the effort they could be friends, just like her father and his sister were.

As children, Denise and Bo had never really got along. Denise was the “good kid”. She did well in school, stayed out of trouble and listened to her parents. Back when they had a shared bedroom, her side was always neat and orderly. Bo’s side was pure chaos. His report cards were never good. He was always finding ways to get out of class, getting in trouble. He was like that even before their parents divorced, but Denise thinks the divorce made things worse. It happened when she was about 13 and it split the siblings apart, Bo went with their father and Denise went with their mother. Denise felt lucky. She remembers her father as angry.

Jim admits he has had to work to become the person he is today, hinting at earlier struggles. He completed a 12-step addiction programme before he got what he describes as a second chance at life.

Denise and Bo

He comes from a very conservative religious background. He remembers thinking people in his church, the Church of Christ, were good, but outsiders – Pentecostals, Baptists – were bad. It was a narrow tunnel vision it took him years to shed, one that his children followed when they were young. Denise told her grade school friends that she wished they would go to church because she was sad they were going to go to hell.

Although he has softened over the years and discarded some of his earlier hard-line viewpoints, Jim still teases Denise for being too liberal. He questions whether Bo would have changed, whether Bo would have used the potential he believes he wasted:

I always wondered what Bo would be. He was a troubled child. But I’ve seen others turn their lives around.”

No-one seems to remember whether Bo graduated from high school. Denise recalls him being into gardening. Both she and her father remember him hanging out at the beach, his hair blond and tousled, his chest bare, just like it was the day he was shot.

He had been at the beach that day. Two African-American girls asked him and his friend for a ride home. That is how Bo, a white boy from an upper-middle-class suburban enclave, ended up in Compton in the 1980s, a time when the crack epidemic was destroying inner cities. Bo wasn’t from that world, but he didn’t think anything of asking two young African-American men where he could get some pot.

He had dropped the girls off by then and was parked outside a liquor store in a neighbourhood where he didn’t belong. At first, Fields thought Bo and his friend were cops. Then, after he figured out they were just clueless kids, he decided to rip them off, by taking their money without delivering the pot.

Denise was coaching soccer that day. It was a Saturday and her team had a game the next day. She was at her mother’s house when one of Bo’s friends came by and told them that Bo had been shot. When they arrived at the hospital a doctor pulled them aside:

We tried to revive him, tried to sew the hole up in his heart. We couldn’t revive him. I’m sorry to tell you, he’s dead.”

That’s what Denise remembers the doctor saying. But it didn’t sink in. Stuff like that didn’t happen where they were from. Denise was sobbing when she called her father. Jim couldn’t understand what she was telling him. It sounded like she was saying Bo was dead.

“But it didn’t make sense,” says Jim. “I mean my son doesn’t die - my son didn’t get killed.”

When he finally understood, Jim imagined a motorcycle accident. Bo had a friend who had been killed in a biking accident not long before. But Bo had been murdered.

Jim went to every legal proceeding: the preliminary hearing, the trial, the sentencing. He took detailed notes. He wanted the death penalty for Fields. He fantasised about bringing a gun to court and shooting the man who killed his only son. Years later, after the terror attacks of 11 September 2001, he started referring to his son’s murder as his personal September 11th.

Denise went to the first day of the trial. She didn’t attend the sentencing, but she telephoned in and said she wanted Fields to be sentenced to life without parole. She became scared of black people. When an elderly African-American couple stopped her to ask for directions she wondered if they wanted to hurt her:

There was just the sense that you don’t know what’s coming - it could come from anywhere.”

She cried through one medical school interview, aced another by mentioning her brother’s murder when asked to talk about trauma. When she graduated from medical school there was no picture of her with her brother like the one taken at her college graduation. He wasn’t there at her wedding or when she had her first and then her second child. But she never forgot him. She mentioned him on the order of service for her wedding and named her first son Jonathan, after him. Jonathan was Bo’s real name but Jim used to call his son “Boy” and as a toddler Denise copied him. It was because her “boy” came out as “bo” that her brother became Bo.

He had been at the beach that day. Two African-American girls asked him and his friend for a ride home. That is how Bo, a white boy from an upper-middle-class suburban enclave, ended up in Compton in the 1980s, a time when the crack epidemic was destroying inner cities. Bo wasn’t from that world, but he didn’t think anything of asking two young African-American men where he could get some pot.

He had dropped the girls off by then and was parked outside a liquor store in a neighbourhood where he didn’t belong. At first, Fields thought Bo and his friend were cops. Then, after he figured out they were just clueless kids, he decided to rip them off, by taking their money without delivering the pot.

Denise was coaching soccer that day. It was a Saturday and her team had a game the next day. She was at her mother’s house when one of Bo’s friends came by and told them that Bo had been shot. When they arrived at the hospital a doctor pulled them aside:

We tried to revive him, tried to sew the hole up in his heart. We couldn’t revive him. I’m sorry to tell you, he’s dead.”

That’s what Denise remembers the doctor saying. But it didn’t sink in. Stuff like that didn’t happen where they were from. Denise was sobbing when she called her father. Jim couldn’t understand what she was telling him. It sounded like she was saying Bo was dead.

“But it didn’t make sense,” says Jim. “I mean my son doesn’t die - my son didn’t get killed.”

When he finally understood, Jim imagined a motorcycle accident. Bo had a friend who had been killed in a biking accident not long before. But Bo had been murdered.

Jim went to every legal proceeding: the preliminary hearing, the trial, the sentencing. He took detailed notes. He wanted the death penalty for Fields. He fantasised about bringing a gun to court and shooting the man who killed his only son. Years later, after the terror attacks of 11 September 2001, he started referring to his son’s murder as his personal September 11th.

Denise went to the first day of the trial. She didn’t attend the sentencing, but she telephoned in and said she wanted Fields to be sentenced to life without parole. She became scared of black people. When an elderly African-American couple stopped her to ask for directions she wondered if they wanted to hurt her:

There was just the sense that you don’t know what’s coming - it could come from anywhere.”

She cried through one medical school interview, aced another by mentioning her brother’s murder when asked to talk about trauma. When she graduated from medical school there was no picture of her with her brother like the one taken at her college graduation. He wasn’t there at her wedding or when she had her first and then her second child. But she never forgot him. She mentioned him on the order of service for her wedding and named her first son Jonathan, after him. Jonathan was Bo’s real name but Jim used to call his son “Boy” and as a toddler Denise copied him. It was because her “boy” came out as “bo” that her brother became Bo.

Over the years Denise had forgotten Fields’s name. But in a strange twist, she had ended up working with men just like him. As a young doctor, she had to work places senior staff didn’t want to go. One of those places was the county jail. Denise didn’t mind. Her new patients were often some of the same people she had treated at the county hospital. In 1997 she took a job at the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo County, a medium-security men’s prison located halfway between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Unlike the men at the jail, those she now treated were there for the long haul. She began to get to know them. Once she knew them a bit, she asked what they were in for. Many of them said murder. They would tell her their stories. She realised they had been in prison for about the same length of time Fields had. Fields, she thought, might, in fact, be like these guys, probably was like them, and she liked these guys. They were “nice people who made mistakes”. She didn’t believe they were evil, at least not the select group of men she worked with at the prison hospice she helped found.

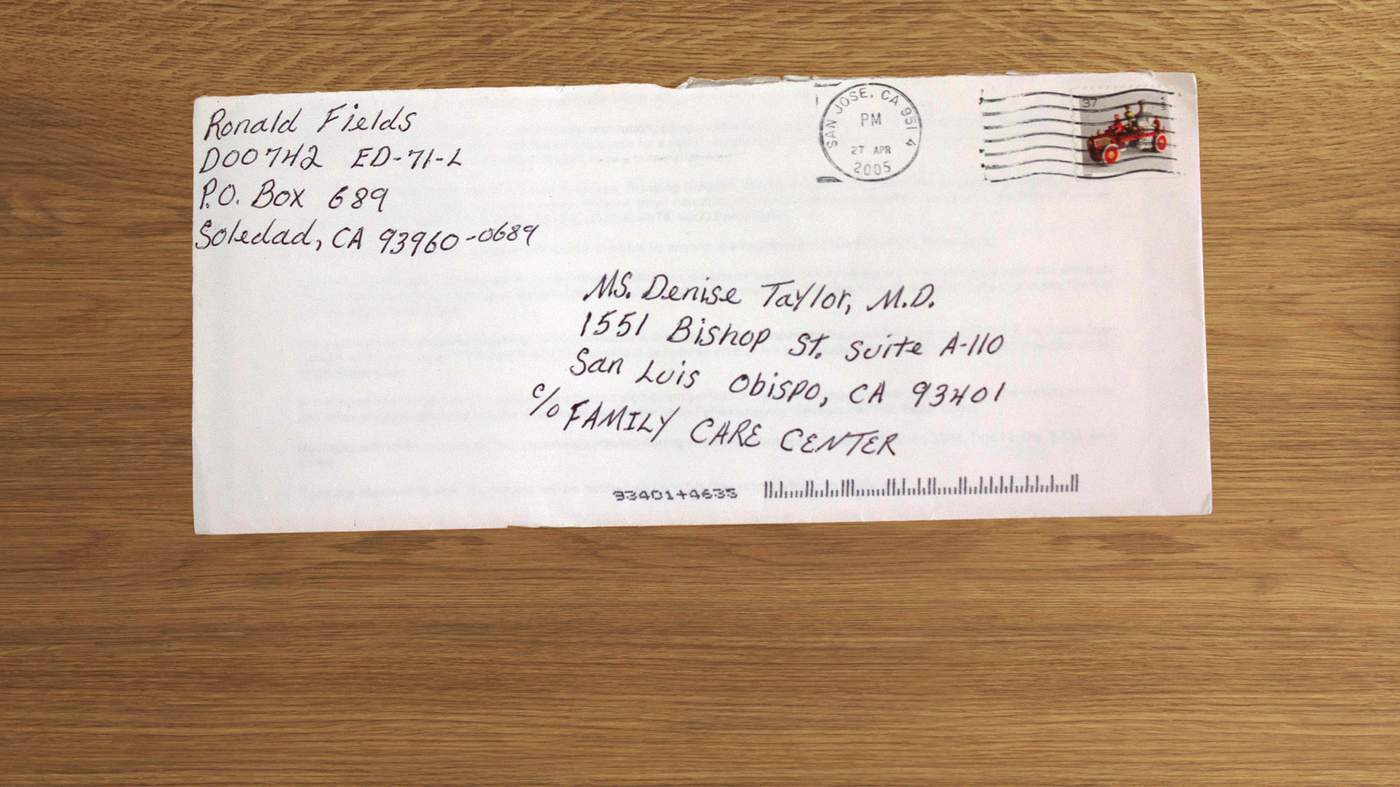

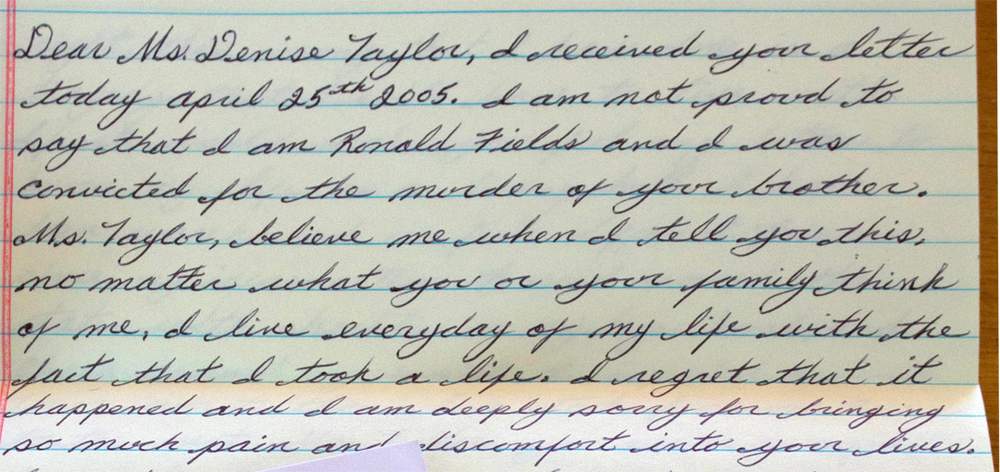

She wanted to know if really, Fields was like them. She had forgiven him, but she wanted to hear him say he was sorry. She didn’t want to make him feel bad, but she wanted her pain acknowledged. She wanted him to understand what he had taken from her and her family. She asked the men she worked with at the hospice, lifers, what they thought of her plan to contact Fields. The lifers told her they would give anything to be able to say sorry to their victims’ families. They told her how hard it was to attend parole hearings, see the families suffering and know they were the cause of that suffering. In 2005 Denise wrote to Fields and asked if she could visit him.

Denise reads Ronnie's letter:

Fields’s reply came back immediately in neat handwriting on lined yellow paper.

“Miss Taylor, believe me when I tell you this: no matter what you or your family think of me, I live every day of my life with the fact that I took a life. I regret that it happened and I’m deeply sorry for bringing so much pain and discomfort into your lives.

Miss Taylor, you made a request to visit me and I am ashamed to see you though I owe your family as much so therefore I will honor your request to visit.”

Denise was familiar with prisons, but this was different. At the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, California, instead of showing her prison identification and breezing through, she had to queue and then wait in a cafeteria-like space with walls painted a ghastly institutional yellow-grey.

Over the years Denise had forgotten Fields’s name. But in a strange twist, she had ended up working with men just like him. As a young doctor, she had to work places senior staff didn’t want to go. One of those places was the county jail. Denise didn’t mind. Her new patients were often some of the same people she had treated at the county hospital. In 1997 she took a job at the California Men’s Colony in San Luis Obispo County, a medium-security men’s prison located halfway between San Francisco and Los Angeles.

Unlike the men at the jail, those she now treated were there for the long haul. She began to get to know them. Once she knew them a bit, she asked what they were in for. Many of them said murder. They would tell her their stories. She realised they had been in prison for about the same length of time Fields had. Fields, she thought, might, in fact, be like these guys, probably was like them, and she liked these guys. They were “nice people who made mistakes”. She didn’t believe they were evil, at least not the select group of men she worked with at the prison hospice she helped found.

Denise reads Ronnie's letter:

She wanted to know if really, Fields was like them. She had forgiven him, but she wanted to hear him say he was sorry. She didn’t want to make him feel bad, but she wanted her pain acknowledged. She wanted him to understand what he had taken from her and her family. She asked the men she worked with at the hospice, lifers, what they thought of her plan to contact Fields. The lifers told her they would give anything to be able to say sorry to their victims’ families. They told her how hard it was to attend parole hearings, see the families suffering and know they were the cause of that suffering. In 2005 Denise wrote to Fields and asked if she could visit him. Fields’s reply came back immediately in neat handwriting on lined yellow paper.

“Miss Taylor, believe me when I tell you this: no matter what you or your family think of me, I live every day of my life with the fact that I took a life. I regret that it happened and I’m deeply sorry for bringing so much pain and discomfort into your lives.

Miss Taylor, you made a request to visit me and I am ashamed to see you though I owe your family as much so therefore I will honor your request to visit.”

Denise was familiar with prisons, but this was different. At the Correctional Training Facility in Soledad, California, instead of showing her prison identification and breezing through, she had to queue and then wait in a cafeteria-like space with walls painted a ghastly institutional yellow-grey.

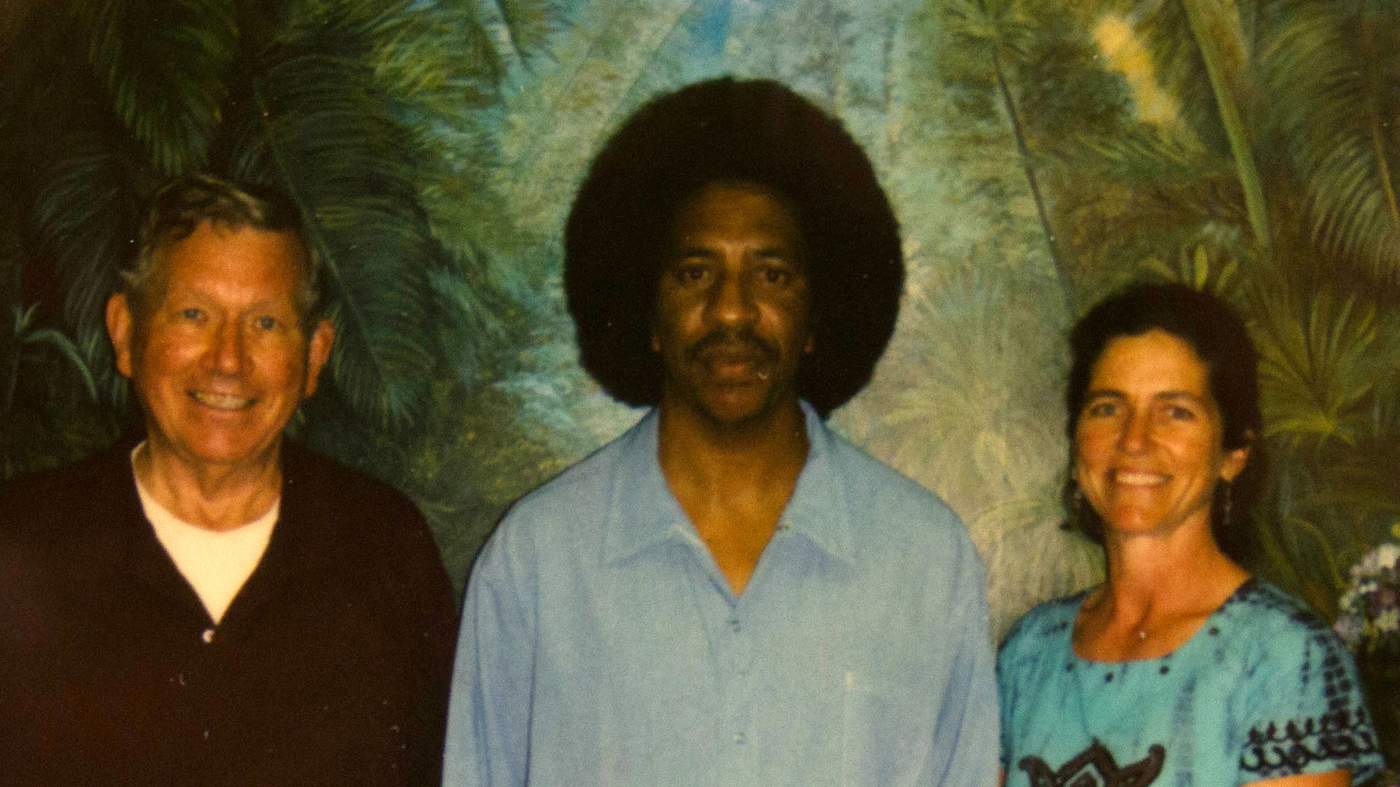

It has been 21 years since Fields murdered her brother. She is told Fields will enter through a door at the opposite end from which she entered. She keeps an eye on the door. She doesn’t even know what Fields looks like. She watches every black inmate who enters, her eyes following them until they inevitably head to a table that is not hers. Then a tall man with a slight Afro haircut walks toward her. Taylor stands up.

“Hi, I’m Denise,” she says, extending her hand.

His grip is firm, but not crushing. “I’m Ronnie.”

They sit down. He is the first to speak:

Can I tell you what happened that horrible day?”

She has to lean in close to hear him. The room is a concrete box off which all the various conversations around them bounce. Every once in a while a guard calls out: “OK, that hug’s long enough,” or “Hands above the table.” Fields doesn’t meet her eyes. He was 24 when he killed Bo. He came from a good family, but he followed his older brothers into a gang. He had gang tattoos, but was never convicted of a gang-related crime.

He dropped out of school in 11th grade when his girlfriend got pregnant. He worked at a car wash, at a used car dealership.

His record was relatively clean, aside from a juvenile charge of taking another kid’s bag. Then he shot Bo. He describes the shooting the same way Taylor has heard it told many times before. He says:

I’m sorry for what I took from you. I’m sorry I’ve caused you this pain.”

Taylor takes out the pictures she brought to show him: photos of her husband and sons. She tells Fields about how her children will never know their uncle, how her husband will never know his brother-in-law. Fields, in turn, tells her about his family: his dead parents, his two brothers behind bars. She is the first visitor he has had in a decade. After two hours Taylor thanks him for letting her visit and gives him a short hug. He doesn’t resist. He walks her to the gate. She tells him she will come again. And she does.The next time she visits she brings her father. It is the first of almost half a dozen parole hearings they attend.

Some family members feel they have to rally against the murderer, demand his or her death in order to honour their lost loved one, says Denise. Society encourages this. Denise does not. Still, she does wonder whether she is betraying her brother. People ask her what Bo would think. She tells them she honestly doesn’t know.

When she told her parents about her first visit to Fields, her mother was OK with it, but expressed no desire to meet him. Her father was another story. Denise feared he would be angry, but he surprised her by being curious. He wanted to know what had happened, why this terrible event had occurred. Jim wrote to Fields about his Christian faith and his religious belief in redemption. Still, the first time he saw Fields, the emotion that flooded him was anger. But it wasn’t anger at Fields. It was anger at the parole board. For Fields, Jim felt compassion. He also felt nostalgia for what he had lost. Now that he knew Fields, he was convinced that Fields had not intended to kill his son. It was just a terrible tragedy. Jim says:

I think maybe 10-15, possibly 20 years, that was justice for Bo, He’s not going to come back. So now the justice I got to worry about is justice for Ronnie. And I don’t think a life sentence is just for him.”

It has been 21 years since Fields murdered her brother. She is told Fields will enter through a door at the opposite end from which she entered. She keeps an eye on the door. She doesn’t even know what Fields looks like. She watches every black inmate who enters, her eyes following them until they inevitably head to a table that is not hers. Then a tall man with a slight Afro haircut walks toward her. Taylor stands up.

“Hi, I’m Denise,” she says, extending her hand.

His grip is firm, but not crushing. “I’m Ronnie.”

They sit down. He is the first to speak:

Can I tell you what happened that horrible day?”

She has to lean in close to hear him. The room is a concrete box off which all the various conversations around them bounce. Every once in a while a guard calls out: “OK, that hug’s long enough,” or “Hands above the table.” Fields doesn’t meet her eyes. He was 24 when he killed Bo. He came from a good family, but he followed his older brothers into a gang. He had gang tattoos, but was never convicted of a gang-related crime.

He dropped out of school in 11th grade when his girlfriend got pregnant. He worked at a car wash, at a used car dealership.

His record was relatively clean, aside from a juvenile charge of taking another kid’s bag. Then he shot Bo. He describes the shooting the same way Taylor has heard it told many times before. He says:

I’m sorry for what I took from you. I’m sorry I’ve caused you this pain.”

Taylor takes out the pictures she brought to show him: photos of her husband and sons. She tells Fields about how her children will never know their uncle, how her husband will never know his brother-in-law. Fields, in turn, tells her about his family: his dead parents, his two brothers behind bars. She is the first visitor he has had in a decade. After two hours Taylor thanks him for letting her visit and gives him a short hug. He doesn’t resist. He walks her to the gate. She tells him she will come again. And she does.The next time she visits she brings her father. It is the first of almost half a dozen parole hearings they attend.

Some family members feel they have to rally against the murderer, demand his or her death in order to honour their lost loved one, says Denise. Society encourages this. Denise does not. Still, she does wonder whether she is betraying her brother. People ask her what Bo would think. She tells them she honestly doesn’t know.

When she told her parents about her first visit to Fields, her mother was OK with it, but expressed no desire to meet him. Her father was another story. Denise feared he would be angry, but he surprised her by being curious. He wanted to know what had happened, why this terrible event had occurred. Jim wrote to Fields about his Christian faith and his religious belief in redemption. Still, the first time he saw Fields, the emotion that flooded him was anger. But it wasn’t anger at Fields. It was anger at the parole board. For Fields, Jim felt compassion. He also felt nostalgia for what he had lost. Now that he knew Fields, he was convinced that Fields had not intended to kill his son. It was just a terrible tragedy. Jim says:

I think maybe 10-15, possibly 20 years, that was justice for Bo, He’s not going to come back. So now the justice I got to worry about is justice for Ronnie. And I don’t think a life sentence is just for him.”

In the beginning, Denise wrote letters almost every month. Eleven years later, she corresponds less often, but she rarely misses a parole hearing. She takes a day off work and drives the hour-and-a-half each way with her father. Each time they have attended a hearing, Fields has been denied parole.

Jim wants Fields to be released while he is still young enough to enjoy freedom. Fields is 56 now, two years older than Denise. He was first eligible for parole in 2001. It is now the end of 2016.

It is almost 11:00 when commissioner Garner announces the decision. He has gone over Fields’s upbringing, his crime and his recovery. He notes that Fields had his gang tattoos removed soon after he arrived in prison and that he has kept his distance from gang members while incarcerated. Now he goes over Fields’s sentence once again. He talks about the rules for parole and legal standards. Denise picks at her cuticles. Fields remains expressionless. Garner continues, “Having these legal standards in mind, we find that you do not pose an unreasonable risk of danger to society or a threat to public safety and are therefore eligible for parole.”

Garner keeps talking, explaining the number of days Fields has to remain in prison while the Governor decides whether to approve or deny his parole, the risks Fields still faces, the challenges ahead. Fields removes his glasses and brings a tissue to his face.

Ronnie expresses regret in this letter

For the first time today he loses his composure. Jim has also removed his glasses and uses the tissue his daughter gives him to cover his face. Deputy commissioner John Denvir continues where Garner left off:

What I personally thought was your strongest area was remorse.”

He continues, “and I think that’s partially because Mr Taylor’s family has, you know, become – and you described them as friends or at least have made themselves available to get to know you.”

Denise keeps the tissue box between her and her father. The commissioners finally stop talking. Fields is taken back to his cell and the Taylors head home. As they walk to the parking lot Jim turns to his daughter:

I feel like I’ve done something good for once in my life.”

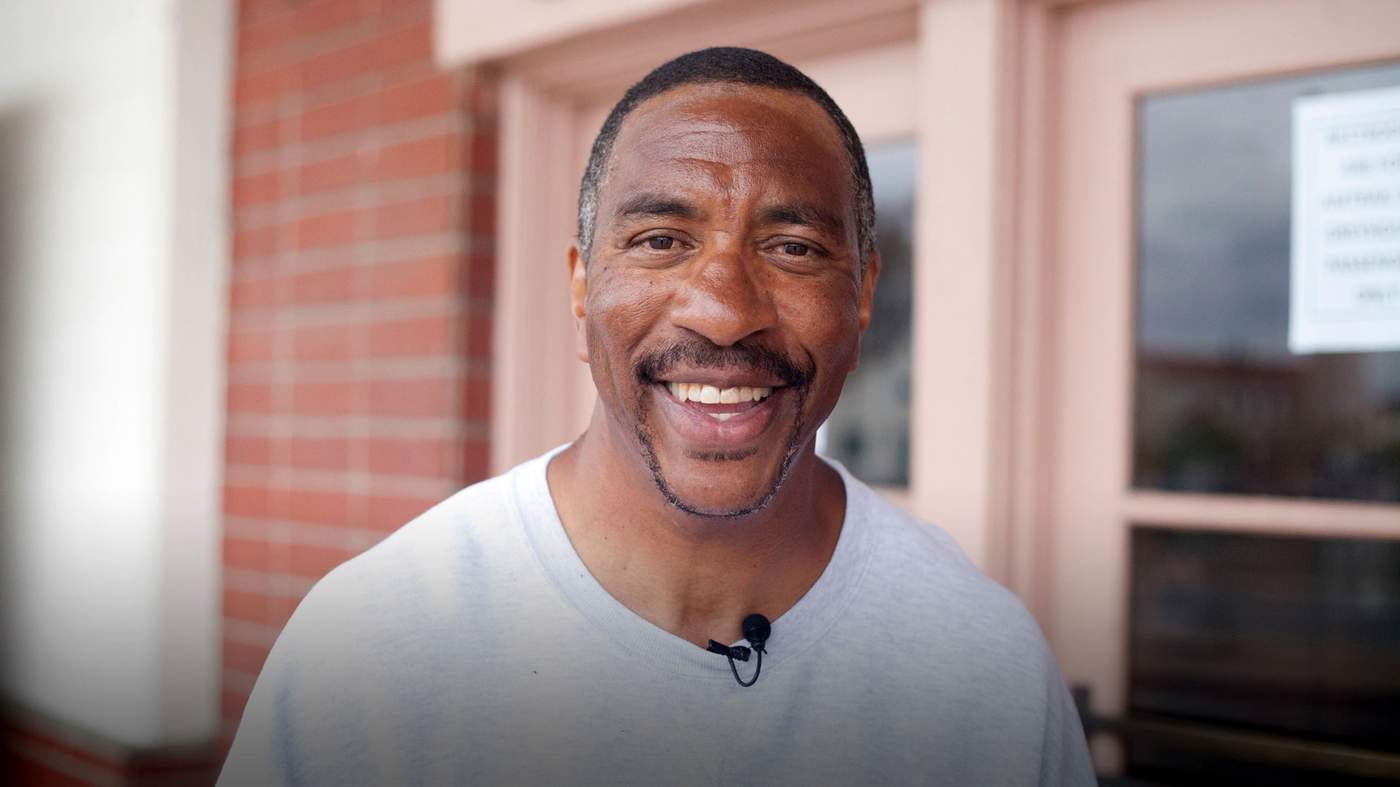

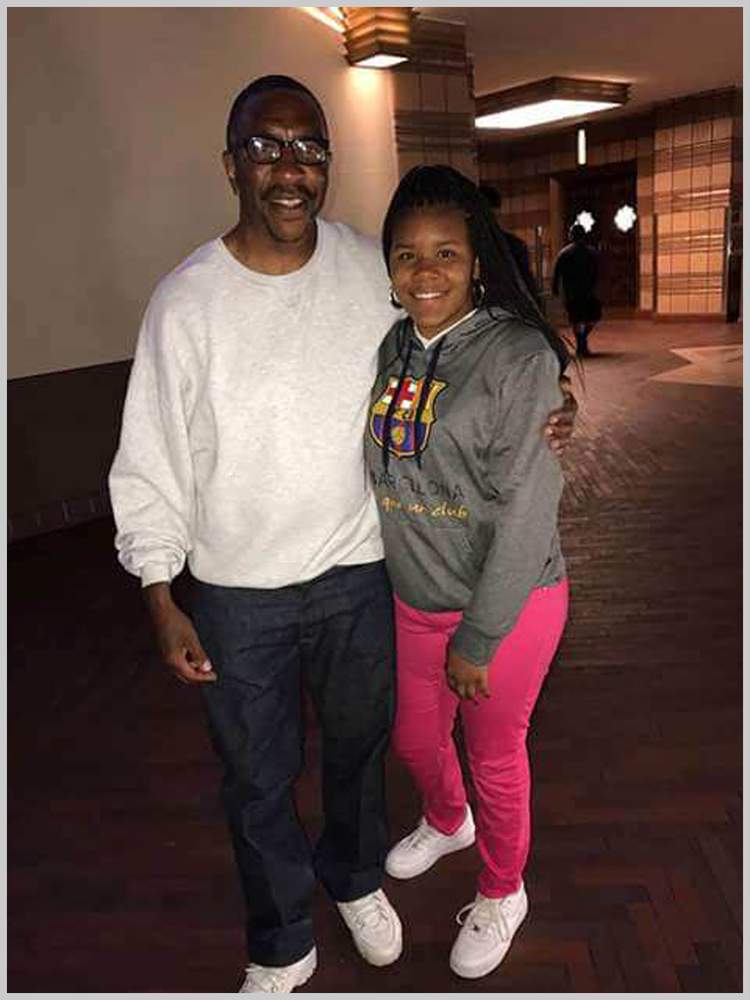

A prison van drops Fields off at the Salinas train station. It is 16 April 2017 and he is out of prison after 32 years, six months and 11 days.

I’m free, I’m finally free I get to sleep somewhere else tonight instead of being in a cage.”

He smiles. It is something he couldn’t do in prison. Inside he had always to maintain his “mean face”. He smiles again thinking about the first meal he wants to eat: a double cheeseburger, large fries and vanilla milkshake from the fast food chain, Carl’s Jr.

Ronnie reacts to being released from prison:

He has been warned that his body may not be ready for real meat after decades of processed meat.

He worries slightly about the long bus ride to Los Angeles - and the risk of getting sick or dizzy - because it has been so long since he has been on a trip. He has heard Los Angeles has been “rebuilt” and isn’t as gang-riddled as he remembers.

He was 24 when he got locked up. Now he takes medication for high blood pressure. All he has in the world is a debit card with $978.33 on it and a plastic tub filled with personal items. The money comes from three decades spent making furniture in the prison for 30 and later 80 cents an hour.

The tub contains a portable CD player and CDs: The Intruders, BWB and David Ruffin. There is also a chess set, photo albums, a very small television and a leather-bound Bible. The Bible is from Jim Taylor. It is the Taylors that Fields credits with his freedom.

I could still be in that prison right now probably for the rest of my life had they chose to oppose my parole and fight to keep me in here as hard as they fought to get me out. I’d probably die in that prison.”

He isn’t sure if he could have done the same if the roles were reversed. When Denise Taylor first came to visit, he says his supervisors warned him not to meet her. They told him it would just upset him. He knew that, he knew she might try to hit him or yell at him. He decided he wouldn’t fight back if she did. He felt he owed her at least that much. But she was pleasant and after that first visit she kept coming back. In time it became clear she and her father weren’t visiting him because they hated him but because they cared about him.

It just made me feel more human, less lost and more civilized, how these people were looking at me.”

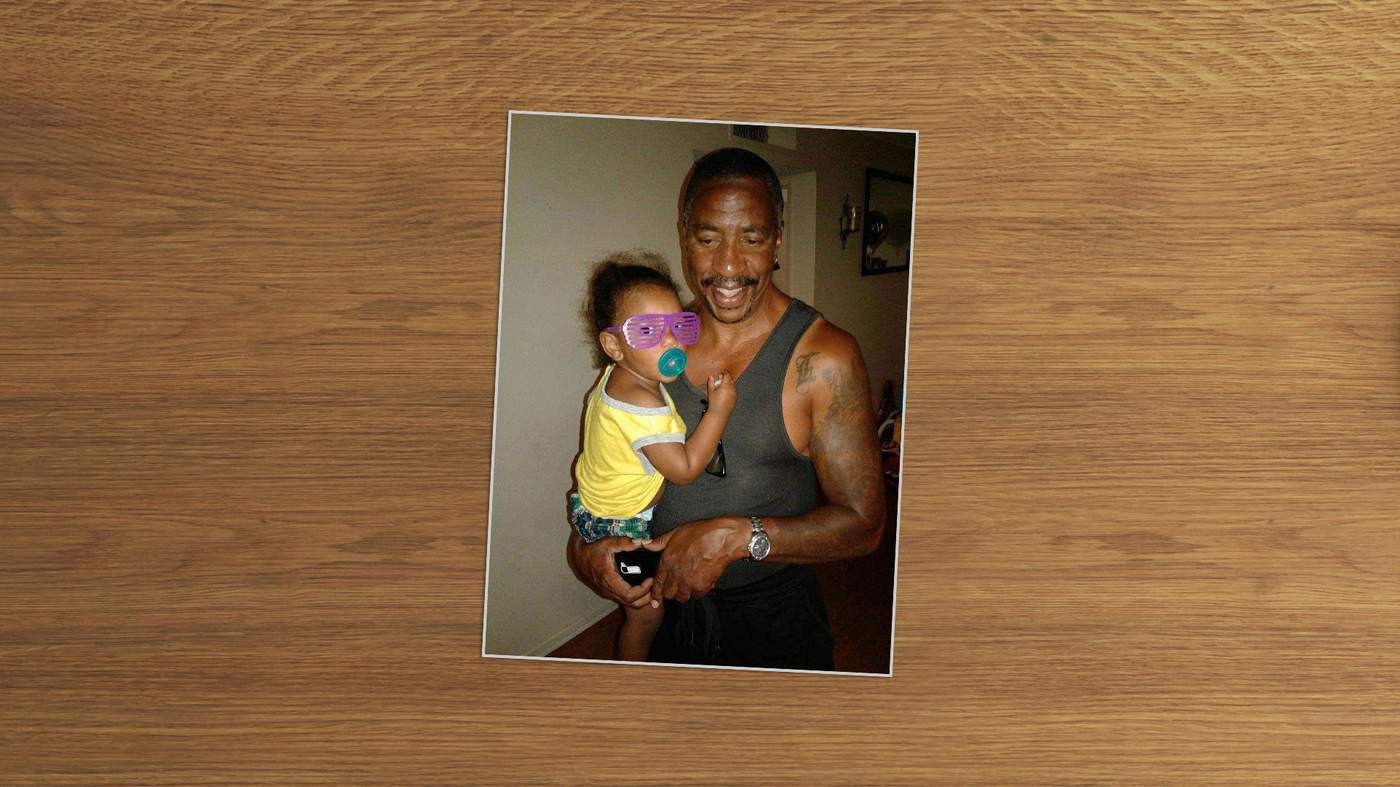

For years they were his only visitors. His grandmother died while he was at Folsom State Prison, one of the five prisons where he served time. His father died in 1993, his mother in 1994. His sister is dead. He has lost track of his brothers, all of whom have also spent time behind bars. He has two sons and a stepson. He has never seen his seven grandchildren or two great-grandchildren except in photos.

On his prison paperwork Denise is listed under next of kin. He sent her his guitar years ago, along with the clothes he planned to wear when he got paroled. When he learned he was finally getting out he called her and asked her to send him the jeans he is now wearing. Jim offered to let Fields live with him, Denise promised to take him shopping for clothes. He appreciates everything they have done, but sometimes it is hard to be with them.

We try to have the best time. But it’s always in me, that guilt is always in me that I took their loved one away from them.”

Fields doesn’t blame the parole board for denying him parole so many times. “I’m a killer,” he says. “They ain’t changed. I have.”

When he went in he might have taken what wasn’t his, but now he says he wants to work for his money. He hopes to get a job operating machines used to make furniture, the same job he performed in prison.

He plans to sign up for government assistance for housing, food and healthcare. But his immediate concern is how he will get from the bus stop to the transitional home where he will be living when he lands in Los Angeles later tonight. A fellow bus passenger offers him her mobile phone so he can call someone to ask for a ride. He looks at the phone.

“How do you use this?”

He doesn’t know how to dial or how to hold it. Finally he punches in his son’s number.

“Hi,” he says. “It’s your daddy.”

Fields meets his granddaughter, for the first time later that night. She is already a young woman. There are other grandchildren, many of them also already grown.

Ronnie with his granddaughter

Three cars filled with relatives are there to greet him when he arrives in Los Angeles around 10pm. A young man jumps out of one of the cars: “Grandpa, I got a 9mm (handgun) and a .45 (pistol) in the car”.

“Which car are you riding in?” Fields asks. He wants to make sure he isn’t in it. That’s how he remembers the conversation. He is on parole for life. Twice a month he has to check in with his parole officer. He has to pee in two separate cups: one to test if he has been drinking, the other to test if he has been smoking marijuana.

Ronnie with his two sons

He calls Denise Taylor almost as soon as he is out. They “friend” each other on Facebook and make plans to meet. Then Fields’s parole officer steps in and says Taylor needs to fill out paperwork before being allowed to communicate with Fields.

In July, permission is given and Taylor makes plans to visit. Fields cancels. They reschedule. A week or so before the meeting, Fields calls and insists the meeting was for a different date and his weekend plans have now been ruined. His impatience is no surprise to the Rev Camira “CC” Carter, house manager of the transitional home where Fields lives. At The Martin Home, most of the 15 male residents are lifers, men who have spent 20 or 30 years in prison.

The challenge I think they face is they want everything quickly. They just want to get so much done, they’ve lost so much time.”

Ronnie and family

When Fields arrived at The Martin Home he was very quiet, Carter says. He kept to himself. Three months later he still stays out of things, especially conflicts, but he is opening up a bit more. A few weeks ago he got a job packing macadamia nuts. He gets up at 03:45 in the morning in order to catch a bus to get him to work by 06:00. He attends all the home’s programmes and meetings and steps up when he sees something needs to be done. Carter believes his relationship with the Taylors has helped Fields stay focused.

“I think it motivates him to say, ‘I'm going to be the best person I can be for as long as I can. Look what I did, and these people have shown me love and mercy,’ and I think that drives him,” she says.

It is a Sunday morning in late July and Carter and Fields are at church in Los Angeles. Fields is seated on the aisle in the back row. He has a mobile phone now and glances at it during slow moments in the service.

Ronnie at church

On his home screen is a photo of him and a number of children, some of them his great grandchildren. While he was in prison he didn’t see any family after his mother died in 1994, but now that he is out they are back in his life. He is even dating Mae again, the mother of his oldest son. When he leaves The Martin Home in another few months he plans to move near Mae and two of his sons. The third son lives in another state. He was a baby when Fields was locked up and calls Fields by his first name “Ronnie” instead of “Dad”. Fields is upset that this son didn’t acknowledge him on his birthday or Father’s Day. So he has cut him off. There it is again, the impatience, the anger.

Taylor notices it after the service when she is driving Fields in her boxy Toyota Scion with its Obama sticker on the windshield and rainbow flag on the dashboard. Fields talks about cars and how much he needs one right away so he can stop spending so much of his time on the bus. Taylor counsels patience, sounding a lot like an older sister. Fields asks after her dad. Then he answers his mobile phone. he says to the person on the other line:

We in Compton, we going to the crime scene.”

It is a place Taylor has never been. After her brother was killed she used to pass the freeway exit that Bo had taken and think, “That’s where it happened.” Coming here with Fields feels like coming full circle.

It is the first time Fields has been back. A lot has changed in the more than three decades he has been away from this city of about 100,000 in Los Angeles County. There is a new freeway, different shops.

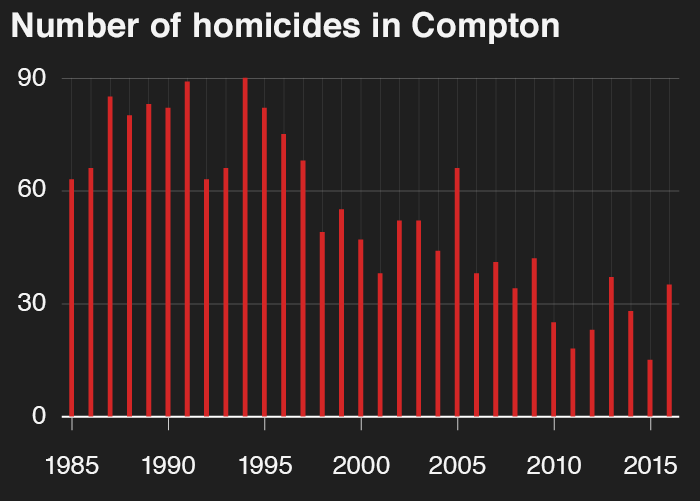

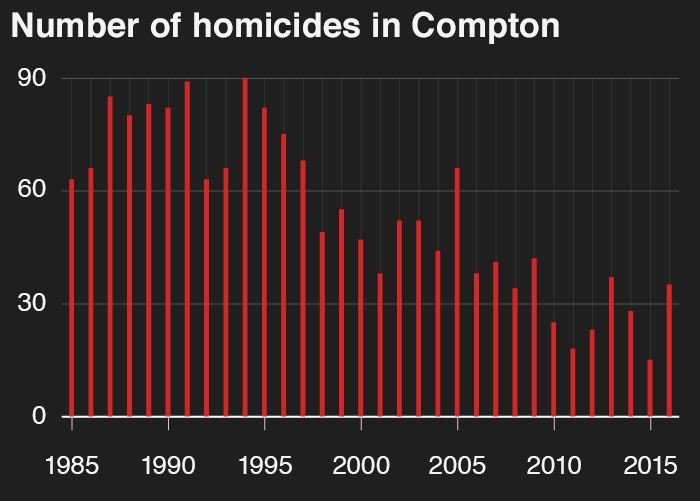

Source: Los Angeles Times

The violent Compton of the 1980s – when the number of murders doubled between 1984 and 1989, reaching 84 homicides in 1989, according to the Los Angeles Times – seems long gone. In 2011 the LA County Sherriff’s Department recorded only 17 homicides in Compton. But they climbed again in 2013 and again in 2016, when they reached 33, according to Los Angeles Times statistics.

Not long after pointing out the liquor store where he met Bo, Fields notes a street blocked off by several police cars: “Ain’t nothing changed out here.”

In Compton, says Fields, a lot of people don’t forgive. Some of his friends think he is a fool for getting in a car with Taylor and going to the site where it all happened, a spot that happens to be in rival gang territory - that is how Fields thought of this area back then and it is still how he thinks of it today. Even though the apartment block the shooting happened outside of has been replaced by a local government building and he no longer belongs to a gang. He checks his phone. His girlfriend, Mae, sent him a text:

Baby be careful. Make sure she don’t have a weapon on her…”

They park and walk to the street corner where it happened. Taylor brings photos of Bo. Over the years the memories have faded, but being here brings them back, makes her brother feel real for her, as if he is alive again. She tears up and turns away from Fields, who remains stiff and guarded. He watches the cars driving by, always on the lookout. He doesn’t feel safe here. He remembers how often people he knew used to get shot. It was normal in his world. To some extent, it still is. He mentions family members from the younger generation who are in trouble with the law, who carry weapons. His two brothers are on drugs: meth and crack.

Ronnie and Denise at the crime scene:

Taylor always knew their lives were different, but before standing on that street corner she hadn’t realised quite how different they were.They leave the site and get lunch, waffles with fried chicken. Taylor pays. As she drives Fields home it is clear to both of them Fields can’t be the replacement brother he once promised to be, mowing her lawn and helping around her house. As her car approaches The Martin Home, Taylor’s phone announces: “Arrived at Ronnie Fields’s home.” They both laugh. Taylor isn’t sure if they will stay in touch. She notices every time Fields recounts the story of the murder he adds a few embellishments, taking a little less responsibility. She says:

He is sorry though. I don’t believe he is going to do it again.”

Then she turns away from the two-storey home with barred windows on Crenshaw Boulevard and drives out of south-west Los Angeles.

It is a Sunday morning in late July and Carter and Fields are at church in Los Angeles. Fields is seated on the aisle in the back row. He has a mobile phone now and glances at it during slow moments in the service.

Ronnie at church

On his home screen is a photo of him and a number of children, some of them his great grandchildren. While he was in prison he didn’t see any family after his mother died in 1994, but now that he is out they are back in his life. He is even dating Mae again, the mother of his oldest son. When he leaves The Martin Home in another few months he plans to move near Mae and two of his sons. The third son lives in another state. He was a baby when Fields was locked up and calls Fields by his first name “Ronnie” instead of “Dad”. Fields is upset that this son didn’t acknowledge him on his birthday or Father’s Day. So he has cut him off. There it is again, the impatience, the anger.

Taylor notices it after the service when she is driving Fields in her boxy Toyota Scion with its Obama sticker on the windshield and rainbow flag on the dashboard. Fields talks about cars and how much he needs one right away so he can stop spending so much of his time on the bus. Taylor counsels patience, sounding a lot like an older sister. Fields asks after her dad. Then he answers his mobile phone. He says to the person on the other line:

We in Compton. We going to the crime scene.”

It is a place Taylor has never been. After her brother was killed she used to pass the freeway exit that Bo had taken and think, “That’s where it happened.” Coming here with Fields feels like coming full circle.

It is the first time Fields has been back. A lot has changed in the more than three decades he has been away from this city of about 100,000 in Los Angeles County. There is a new freeway, different shops.

Source: Los Angeles Times

The violent Compton of the 1980s – when the number of murders doubled between 1984 and 1989, reaching 84 homicides in 1989, according to the Los Angeles Times – seems long gone. In 2011 the LA County Sherriff’s Department recorded only 17 homicides in Compton. But they climbed again in 2013 and again in 2016, when they reached 33, according to Los Angeles Times statistics.

Not long after pointing out the liquor store where he met Bo, Fields notes a street blocked off by several police cars: “Ain’t nothing changed out here.”

In Compton, says Fields, a lot of people don’t forgive. Some of his friends think he is a fool for getting in a car with Taylor and going to the site where it all happened, a spot that happens to be in rival gang territory - that is how Fields thought of this area back then and it is still how he thinks of it today. Even though the apartment block the shooting happened outside of has been replaced by a local government building and he no longer belongs to a gang.

He checks his phone. His girlfriend, Mae, sent him a text:

Baby be careful. Make sure she don’t have a weapon on her…”

They park and walk to the street corner where it happened. Taylor brings photos of Bo. Over the years the memories have faded, but being here brings them back, makes her brother feel real for her, as if he is alive again. She tears up and turns away from Fields, who remains stiff and guarded. He watches the cars driving by, always on the lookout. He doesn’t feel safe here. He remembers how often people he knew used to get shot. It was normal in his world. To some extent, it still is. He mentions family members from the younger generation who are in trouble with the law, who carry weapons. His two brothers are on drugs: meth and crack.

Ronnie and Denise at the crime scene:

Taylor always knew their lives were different, but before standing on that street corner she hadn’t realised quite how different they were.They leave the site and get lunch, waffles with fried chicken. Taylor pays. As she drives Fields home it is clear to both of them Fields can’t be the replacement brother he once promised to be, mowing her lawn and helping around her house. As her car approaches The Martin Home, Taylor’s phone announces: “Arrived at Ronnie Fields’s home”. They both laugh.Taylor isn’t sure if they will stay in touch. She notices every time Fields recounts the story of the murder he adds a few embellishments, taking a little less responsibility.

He is sorry though. I don’t believe he is going to do it again.”

Then she turns away from the two-storey home with barred windows on Crenshaw Boulevard and drives out of south-west Los Angeles.