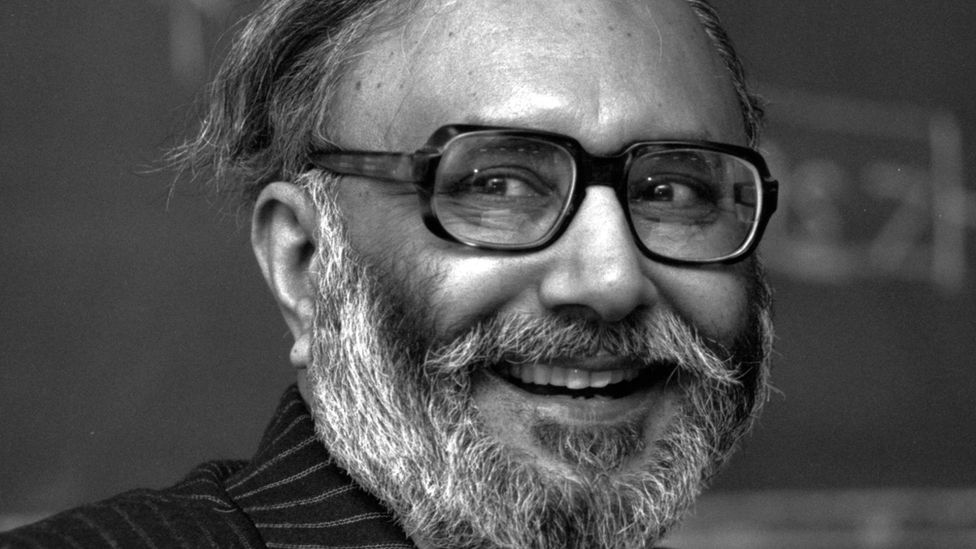

Why has this Nobel winner been ignored for 30 years?

- Published

In 1980, soon after Pakistani professor Abdus Salam was awarded the Nobel Prize for his contribution to developing the theory of electroweak unification in particle physics, he was invited to a ceremony at the Quaid-e-Azam University (QAU) in Islamabad.

Few at the time expected the decision would backfire.

But it did, and the reason was because of sectarian hatred unleashed by a 1974 law that declared the Ahmadi community - to which Dr Salam belonged - as non-Muslim.

"The ceremony was organised to honour Dr Salam, and was to be held at QAU's Department of Physics, which was founded by one of his former students, Dr Riazuddin," says Pervez Hoodbhoy, a well-known Pakistani physicist, academic and security analyst who was among the organisers.

Dr Salam arrived in Islamabad to attend the ceremony, but couldn't enter the QAU premises due to fierce agitation started by student members of the powerful political and religious wing of the Jamaat-e-Islami party.

"The situation grew extremely tense; I clearly remember, they were threatening that they would break Dr Salam's legs if he dared enter the university campus; we had to call off the programme," Mr Hoodbhoy recalls.

Move on some 37 years later and Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif on Monday surprised many by approving a plan to rename that same department of the QAU as the Dr Abdus Salam Centre for Physics.

He also approved five annual scholarships for Pakistani students competing for doctoral programmes in physics at overseas universities.

Many have welcomed the decision. Dawn newspaper, in an editorial comment on Wednesday, expressed hope that "a historic wrong is finally on course to being set right".

"That it has taken nearly four decades for this country to honour a globally renowned scientist who was one of its own, is a sad reflection of the priorities that hold sway here... For Dr Salam was an Ahmadi, a persecuted minority in Pakistan, and his faith rather than his towering achievements was the yardstick by which he was judged," Dawn noted.

Religious extremism

Abdus Salam was born to a family of modest means in the Jhang region of central Punjab in 1926. He studied maths at Government College Lahore and earned a scholarship to the University of Cambridge where he completed his doctorate in 1951.

Between 1960 and 1974 he worked as an advisor to the Pakistani president on scientific matters, and is widely credited with laying the foundations of both the country's space and nuclear programmes.

He left the country in 1974 in protest over the enactment of a constitutional amendment that declared Ahmadis as non-Muslims, but in doing so did not sever links with the scientific community in Pakistan.

During this period, a rising tide of religious extremism backed by powerful quarters in the military establishment led to the creation of a furiously anti-Ahmadi social narrative which has still not run out of steam.

As such, his not an inspirational story in Pakistan, and there is no mention of him in textbooks.

Until recently, any public mention of Dr Salam as a hero invariably provoked a backlash from what many call the "guardians of faith".

So why did Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif take the gamble of honouring him now - so long after his death in Oxford in 1996 at the age of 70?

It appears that the immediate trigger came through a rare TV programme commemorating the 20th anniversary of Dr Salam's death on 29 November, which the prime minister happened to be watching, according to a credible source.

Soon after the programme, he rang up one of the participants in the programme to recommend naming the National Centre of Physics after Dr Salam.

But more significantly, the prime minister's decision came in the wake of a similar controversy which followed news that that one of the four candidates for the head of Pakistan's army, Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa, was married to a woman who had Ahmadi relatives.

Gen Bajwa's selection by the prime minister despite this campaign, and the fact that the army did not object to it, appears to have silenced the anti-Ahmadi groups for the moment.

Who are the Ahmadis?

- The Ahmadi movement has its origins in British-controlled northern India in the late 19th Century

- It identifies itself as a Muslim group which follows the teachings of the Koran

- But it is regarded by orthodox Muslims as heretical because it does not believe that Mohammad was the final prophet sent to guide mankind, as orthodox Muslims believe is laid out in the Koran

- The community takes its name from its founder Mirza Ghulam Ahmad, who was born in 1835 and was regarded by his followers as the Messiah and a prophet

- In 1947, the community moved its religious headquarters from Qadian in India to Rabwah in Pakistan

- In 1974, under severe pressure from clerics, Pakistan's first elected Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto introduced a constitutional amendment - known as the second amendment - which declared Ahmadis as non-Muslims

- A decade later, a new law was brought in barring Ahmadis from calling their places of worship mosques or from propagating their faith in "any way, directly or indirectly"

- Described by rights organisations as one of the most relentlessly persecuted communities in Pakistan, the Ahmadis have seen their personal and political rights deteriorate steadily over the years

The prime minister appears to have seized this moment to correct the wrong Pakistan has done to Dr Salam, believes Pervez Hoodbhoy.

"The decision shows that Pakistan wants to become a 'normal' country, and Nawaz Sharif would like to change its image from a state promoting extremist ideologies to one that can overcome obscurantism and own up to its heroes, Muslim or no Muslim," he says.

But the shift, if there is one, is only just beginning, and some elements have already made what is being seen as a feeble attempt to throw a spanner in the works.

On the very day the prime minister honoured Dr Salam, a police party raided the Ahmadi sect's headquarters in the town of Rabwah. They arrested four people and sealed a printing press which they said was printing "hate material".

An anti-Ahmadi group claimed on its website the raid was conducted following its complaint.

It seems the road to normalisation is not going to be without blockages.

- Published10 April 2016

- Published25 May 2015

- Published30 September 2014

- Published30 September 2014

- Published25 December 2013

- Published29 May 2010