Alan Shearer: Making my documentary Dementia, Football and Me

- Published

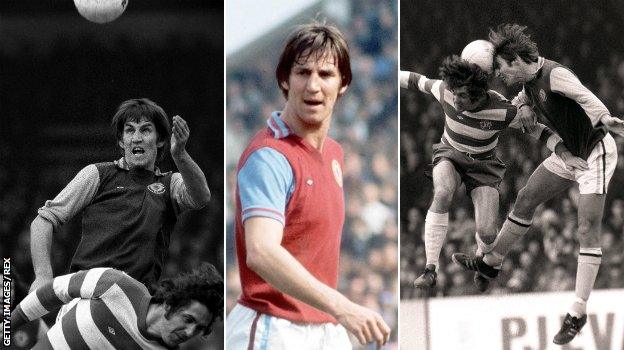

Alan Shearer had an MRI scan to find out if his brain had been damaged by his playing career

Dementia, Football and Me - BBC World News |

|---|

Dates: Saturday, 16 December 01:10 GMT (except the North and Latin America region) and 15:10 GMT. Sunday 17 December 09:10 GMT and 20:10 GMT |

It is more than a year since I started making my BBC documentary investigating the link between heading footballs and dementia.

Personally and professionally, it has been quite a journey - and also an education - for me.

I met former footballers and their families who live with the disease, spoke to scientists and doctors about the research that is taking place, and took part in tests myself.

As someone who played the game for 20 years, and sometimes headed the ball up to 100 times a day in training, I knew that if there was a danger, then I was one of those who could be at risk.

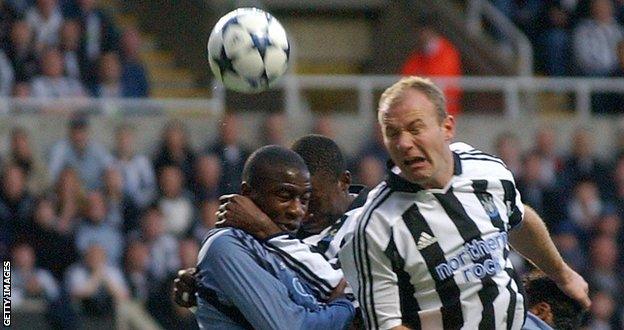

Shearer is the Premier League's leading goalscorer with 260 goals for Blackburn and Newcastle, including 46 headers. As well as in matches, he headed the ball thousands of times in training during his career.

My aim was to learn as much as I could about the subject, and the people it affects.

At times, it was hugely emotional, but I really enjoyed it too - and I am very proud of the programme we have made together.

Asking for answers - and not getting any

What touched me the most was meeting retired players, and their relatives, who are living with dementia.

It made me realise that this is a horrific disease that does not just affect those who have it, but the people around them too.

People like Dawn Astle, daughter of Jeff Astle, the former West Brom and England striker who suffered from dementia before dying at the age of 59 in 2002.

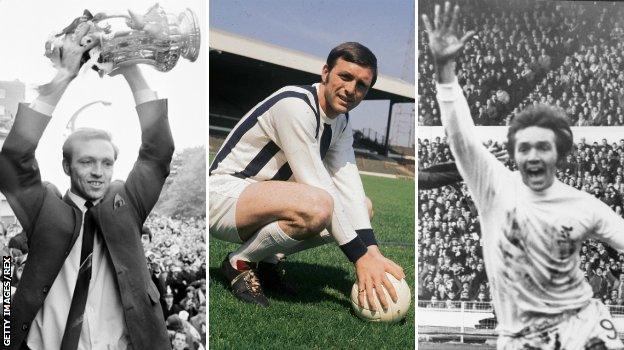

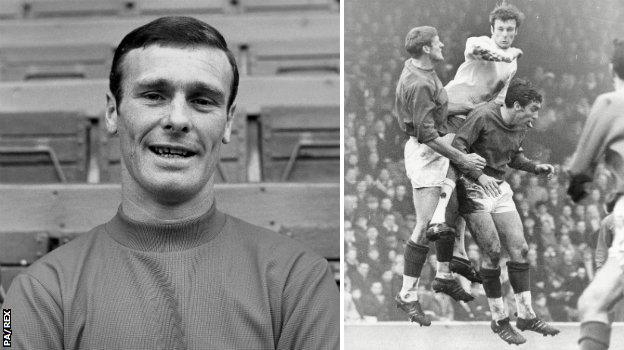

Jeff Astle scored 174 goals in 361 games for West Brom between 1964 and 1974 and was part of the England squad at the 1970 World Cup. He scored the winner in the 1968 FA Cup final and became the first player to score in the final of both major English cup competitions at Wembley when he scored in the 1970 League Cup final

At the inquest into his death, the coroner said the damage to Astle's brain had been caused by years of heading a football.

The ruling was industrial disease, so we knew something about this subject then, 15 years ago.

We hear a lot about footballers having problems with drink, drugs or gambling, and the football authorities have put measures in place to help them.

Similarly, after Bolton midfielder Fabrice Muamba almost died of a cardiac arrest on the pitch in 2012, defibrillators were put at every ground within a matter of months.

All of that has helped to save lives. Yet very little has been done to investigate the effects of heading a ball. I find that staggering.

Shearer met Jeff Astle's daughter Dawn, a long-term campaigner about the links between heading balls and dementia, who launched the Jeff Astle Foundation in 2015 to promote education, awareness and further research

I expected dodgy knees - but not the chance of brain damage

Dawn was upset when she was talking about what happened to her dad and I understand why.

She had asked for answers and did not get any, and it felt like no-one had even been listening to her.

That gave me even more strength and determination to go and delve deeper into the issue and the lack of action about it.

There is a lot of anger out there, because people feel the football authorities have ignored them and they have not had any support. I have huge sympathy for them.

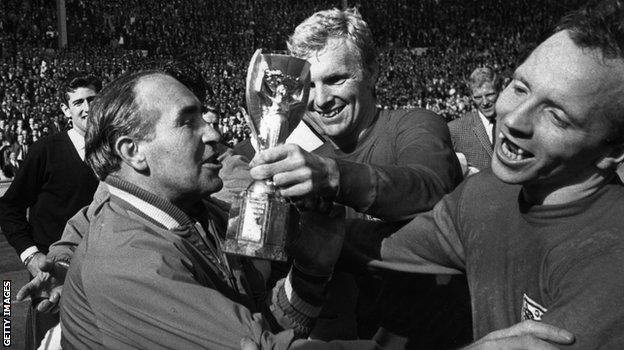

Nobby Stiles, 75, shown here celebrating with Sir Alf Ramsey and Bobby Moore after winning the 1966 World Cup, also won two league titles and the European Cup during an 11-year spell at Manchester United

It was the same when I spoke to John Stiles, the son of legendary 1966 England World Cup winner Nobby, who is now in the advanced stages of dementia.

These people know it is too late for their loved ones, but they want something done to find out why it happened and if it can be prevented, so future generations do not suffer in the same way.

As I say in the documentary, I went into football knowing that at the end of my career I could probably expect to have some physical issues, which I do - I have dodgy knees, a dodgy back and dodgy ankles.

But what I never contemplated for a second back then was that there is a chance that heading the ball could affect my brain.

If that is the case, then people need to be aware of it.

There is help out there but more work is needed

It is not just big-name England strikers and World Cup winners who are affected, it is everyone who played the game, and I think it is important to give everyone a voice.

I also went to see Matt Tees, a prolific goalscorer in the 1960s and 70s, who was known for his heading ability and played for Grimsby, Charlton and Luton, among others.

Scottish striker Matt Tees, 78, pictured here during his time at Charlton, scored 93 goals in 196 appearances during two spells at Grimsby Town from 1963 to 1967 and 1971 to 1973. He was 6ft 4in and was renowned for his bravery and his heading ability, scoring a total of more than 200 career goals north and south of the border

He was loved by the fans of the clubs he played for but the joy he got from his career is gone now because of dementia - he cannot remember who he played for, and does not even know where he lives.

I met Matt, and his wife May, and saw what she has to go through every day. It was incredibly hard to watch.

From the time I spent with them, I saw there are now community support groups out there, which offer May some respite and give some social interaction for both of them.

But, at the same time, it is clear a lot more work is needed to get out the message that, if you are living with the disease, you are not alone.

Chris Nicholl, 71, handed a 17-year-old Shearer his senior professional debut in 1988 when he was Southampton manager. As a player, the Northern Ireland international was a commanding centre-half who won two League Cups with Aston Villa in the 1970s and scored a spectacular long-range goal against Everton in the 1977 final

There are former players out there who think they might have a problem, but have not had a diagnosis.

My old Southampton manager Chris Nicholl, the man who gave me my break in football, is also struggling.

Chris thinks his difficulties might be caused by heading balls but he carries on as normal, as if he is suffering from a physical injury I suppose.

That is part of the issue here. He needs advice and information, and so do other ex-footballers who might have been affected.

Taking the tests myself

Shearer underwent a series of tests at Stirling University immediately before and after taking part in heading drills, using a ball fired from a machine to simulate the velocity of a corner kick

I got the idea for the documentary in 2016 when I watched the film 'Concussion', which examined links between repeated blows to the head and brain damage in retired NFL players.

It really struck a chord with me, because heading was such a big part of my game and to get better at it I used to practice, practice, practice.

I thought it was hugely important that, if I was making this programme, then I had to take part in the studies myself.

Shearer had his balance, reaction times and memory tested by experts at Stirling University before and after heading the ball, and the results were compared

And I also wanted to know if my own brain had been damaged by my playing career, even if I was very nervous about doing so because I was worried about my own health.

I underwent an MRI scan on the chemical and structural detail of my brain at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital in Glasgow.

You will have to watch this weekend to see the results.

Shearer in the MRI scanner at the Queen Elizabeth University Hospital. "You can tell on the documentary how nervous I was going in," said Shearer. "I've got a terrible memory but I don't know if that is because I don't listen. One of the things they said to me beforehand was that, if they found anything wrong, they would have to tell me"

Are people beginning to listen?

The final people I spoke to on my journey were the Football Association and the Professional Footballers' Association.

I wanted to know if they are trying to provide some of the answers that the people I had met were demanding about the link between heading footballs and dementia.

Clearly, there is a lot of work still to be done but, from the response I got, it seems that the people who govern the game are beginning to listen.

If this documentary can help that happen more, or even just build awareness, then it has been worthwhile. Making it has been eye-opening for me.

Alan Shearer was speaking to BBC Sport's Chris Bevan.

- Published13 November 2017

- Published14 January 2018

- Published8 August 2017

- Published7 June 2019