The seats that could decide the election

- Published

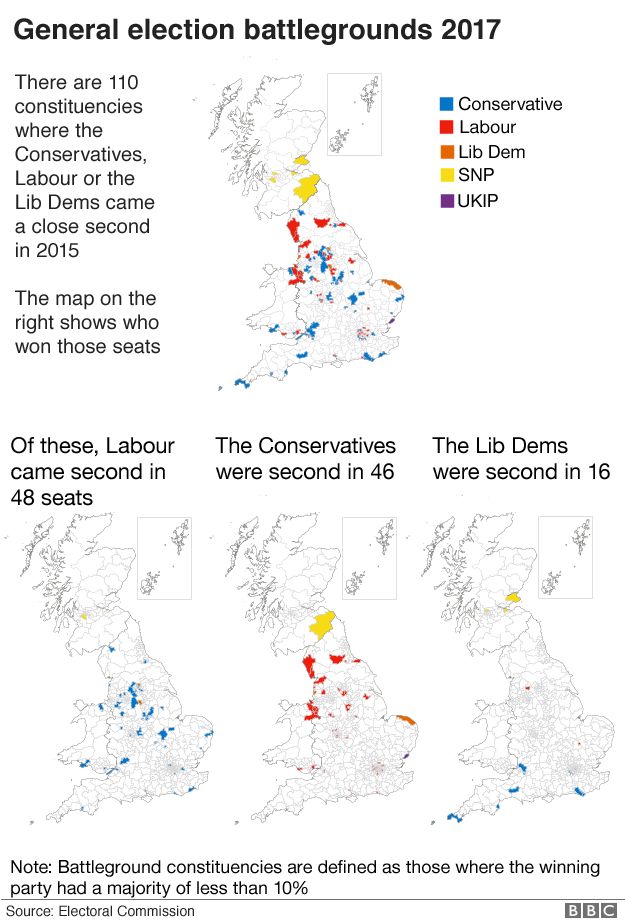

There are 650 constituencies in the United Kingdom. But the election campaign over the coming weeks will be concentrated in the marginal battleground seats - the ones with small majorities that are most likely to change hands.

There's no official definition of a marginal seat but people often look at constituencies where the majority - the gap between the first and second placed parties - is under 10%.

For politicians it's obviously a good idea to focus on these battleground seats. There's not much point in spending lots of time and money in constituencies that they already hold comfortably, or where they're so far behind they have no realistic chance of winning.

There are exceptions to this. In 2015 the SNP surge in Scotland was so powerful that apparently "safe" seats fell. And the collapse of the Lib Dems saw them lose some seats they'd held with sizeable majorities.

Such large swings are rare though. And even in 2015 the Conservative/Labour fight took place almost exclusively in the battleground seats.

Eighteen seats changed hands between the two biggest parties. Only one of those, Ilford North, had a majority above 10%.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this content.

Conservative targets

Seats the Conservatives will be gunning for include Middlesbrough South and Cleveland East, Birmingham Edgbaston and Wirral West.

Recent elections have seen poor returns for the Conservatives in the north-east of England but it's a part of the country that voted strongly for Brexit and Prime Minister Theresa May hopes her focus on the issue will help them gain seats.

Labour-held Middlesbrough South and Cleveland East is a good example. Its voters backed Brexit and there's a considerable pool of almost 7,000 voters who went for UKIP last time.

That's one group the Conservatives will target. If they trust Theresa May to deliver Brexit, the Conservatives will argue, why vote UKIP? Picking up a decent chunk of them would be enough to overturn Labour's majority of 2,268.

Other pro-Brexit Conservative targets in the north of England and the Midlands include Halifax, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Derbyshire North East and Walsall North. In all of them there's a sizeable number of people who voted UKIP in 2015 and a small Labour majority.

Birmingham Edgbaston is a different sort of target. Its voters were fairly evenly split on Brexit. But it's a relatively prosperous part of the city which used to be a Conservative stronghold.

An increase in the number of ethnic minority voters helped Labour last time round but it's always remained in the Conservatives' sights. With Gisela Stuart standing down after 20 years as the MP, they'll see an opportunity.

Wirral West is one of 10 seats lost by the Conservatives to Labour in 2015 - Esther McVey was ousted as the MP after just one term.

With their current lead in the opinion polls, they'll be highly optimistic they can take it back - along with other seats lost in 2015 such as City of Chester, Dewsbury and Lancaster and Fleetwood.

Labour targets

Labour start the election as the clear underdogs compared to the Conservatives. But Labour leader Jeremy Corbyn hopes to win over voters during the campaign.

Their top targets include Gower, Croydon Central and Renfrewshire East.

Gower, in South Wales, has the smallest majority of any seat in the country - a mere 27 votes. If just 14 voters switched from the Conservatives, Labour would take it so they will be campaigning for every vote. Before 2015 they'd held it for more than 100 years and it had been considered a Labour heartland seat.

Other losses from 2015 they'll want to reverse include Morley and Outwood, former Labour shadow chancellor Ed Balls's old seat, and Plymouth Sutton and Devonport.

In recent years London has been Labour's strongest region. They made seven gains here in 2015 and Sadiq Khan went on to win the 2016 mayoral election comfortably.

Croydon Central was a seat they narrowly missed out on last time but they reduced the Conservative majority to just 165 votes. In a sign of their intentions, Jeremy Corbyn went to the constituency on the very afternoon that MPs voted to allow the early election.

Hendon and Harrow East are other London targets

Labour lost 40 Scottish seats to the SNP in 2015. In many cases the swing was so massive that they now look beyond reach.

But they'll be looking for any signs of the beginning of a fight back. RenfrewshireEast, which used to be Scottish Labour leader Jim Murphy's seat, is their top target. Next down the list is Edinburgh North and Leith.

Lib Dem targets

The Lib Dems are starting from a low base. They lost 49 seats in 2015, holding on to just eight, and are looking for a recovery this time.

Their targets include Twickenham, Dunbartonshire East and Yeovil.

As the most pro-EU of the national parties, the Lib Dems will particularly target seats like Conservative-held Twickenham in London, which voted heavily for Remain in last year's referendum and where Sir Vince Cable is returning to refight his old seat.

The December 2016 by-election in neighbouring Richmond Park, where they overturned Conservative Zac Goldsmith's 23,000 majority, showed their strategy could work.

Other pro-Remain constituencies in their sights include Kingston and Surbiton and, outside of London, Bath and Cambridge - the latter held by Labour.

Dunbartonshire East also voted for Remain but here they must challenge the SNP, another strongly pro-EU party. Nevertheless, the Lib Dems will think they have a chance.

Jo Swinson was ousted there in 2015 when the SNP's vote surged by 30%. She's standing again and won't need much of that back to recapture the seat.

The pro-EU message probably won't go down so well in Yeovil, which backed Leave in the referendum. But it's a constituency that the Lib Dems held for more than 30 years before it went Conservative in 2015 - Paddy Ashdown used to be the MP - and the broader south-west region used to be a stronghold for the party.

Other targets here include Thornbury and Yate, on the outskirts of Bristol, and St Ives in Cornwall - a county where the Lib Dems used to dominate.

Other parties

With the SNP already holding 56 out of 59 seats in Scotland it's clearly impossible for them to make significant gains. But they'll be gunning for Labour's only Scottish constituency, Edinburgh South, and they're not far behind in Lib Dem-held Orkney and Shetland.

Plaid Cymru are just 229 votes behind Labour in Ynys Mon (Anglesey). But there could also be an intriguing battle in Rhondda if party leader Leanne Wood decides to stand, even though mathematically it's a lot further down the target list. She achieved a tremendous 24% swing there in the Welsh Assembly election last year, so a gain is not out of the question.

UKIP's results in 2015 demonstrated again how parties can suffer under the first-past-the-post electoral system.

They received 3.9 million votes but won just one seat, Clacton, and even there the victor was Douglas Carswell, who had defected from the Conservatives.

The problem UKIP have is that their vote is very evenly distributed compared to the other main parties - in fact, so much so that they're not even a close second in many places.

Former leader Nigel Farage fell 3,000 votes short in Thanet South last time. They're also close in Hartlepool where the Labour MP is standing down so that may be their best chance.

The Green Party are also badly served by first past the post. The only seat where they start in second place within 10% of the winner is Labour-held Bristol West. The Lib Dems are also a significant presence in that constituency and even the fourth-placed Conservatives got nearly 10,000 votes in 2015 so there a lot of possible outcomes.

Northern Ireland

It may be only two years since the last general election. But in Northern Ireland it's less than two months since voters last went to the polls. The Assembly election held on 2 March saw gains for Sinn Fein and losses for the main unionist parties (UUP and DUP). It would be wrong to assume the general election will automatically follow the same pattern but it will certainly have an impact on the campaign.

Sinn Fein will be eager to recapture Fermanagh and South Tyrone - reversing the loss they suffered in 2015. The swing they achieved in March would be enough to get them over the line.

Belfast South is a rare three-way marginal. Both the DUP and the Alliance Party (APNI) are within 10% of the incumbent SDLP. In fact Sinn Fein is less than 11% behind as well so there are lots of possible outcomes. Perhaps the most important factor, here and elsewhere, will be whether all the parties stand. In 2015 the DUP and UUP agreed to co-operate by standing aside for each other in four constituencies. That certainly helped and the UUP have already announced they'll do the same again. Previously the SDLP have refused to enter any deal with Sinn Fein but they are thinking of doing so this time as part of a broader anti-Brexit alliance. That could change the complexion of a number of battleground seats.

The contest in South Antrim is different. It has an overwhelming majority of unionist voters. The question is whether they'll back the UUP or DUP. The seat has switched between the two parties four times this century. It wouldn't take much of a shift for it to switch again.

- Published2 May 2017

- Published2 June 2017

- Published30 December 2020