“It is something I will never forget,” says Joan Punyet Miró, standing on the threshold of the Majorcan studio where his grandfather, the acclaimed Spanish artist Joan Miró, worked from the late ‘50s almost until his death in 1983. “It was 20 April 1978: my grandfather’s 85th birthday. I was 10 years old. He clapped his hands and said, ‘Joan, today we will walk down to my studio.’”

Even though Joan Punyet had grown up nearby in Palma, the island’s capital, and usually visited his grandfather twice a week, this was the first time that he had been allowed inside the eye-catching atelier designed by Miró’s friend, the Spanish architect Josep Lluis Sert.

Mirós atelier was designed by his friend the architect Josep Lluis Sert (Credit: Travelstock 44/Alamy)

Few people were invited into this fantastical building overlooking the Mediterranean, with its distinctive, undulating white roof like a pair of seagull wings, and shutters of bright blue, yellow and red, recalling paintings by the artist.

To me, as a boy, he was not the great Miró: he was grandpa – Joan Punyet Miró

The interior, dominated by a primitive-looking wall of rough-hewn boulders, yet awash with beautiful light, was a sanctuary where the artist could summon his phantasmagorical art in peace. Although Miró was a fan of music, he insisted on silence while he worked – and he certainly did not encourage his grandchildren to play in his vicinity when he was painting.

The interior of Miró’s studio features a wall of rough-hewn boulders and is flooded with Mediterranean light (Credit: LOOK GmbH/Alamy)

“So I felt extremely honoured,” recalls his grandson, a flamboyant poet and performance artist dressed in a tweed sports jacket, yellow-framed sunglasses, and smart leather shoes. “Smelling the turpentine, oil paints and acrylics, and seeing hundreds of works all over the place: that day with my grandfather was a striking experience.” He pauses. “To me, as a boy, he was not the great Miró: he was grandpa. Only when I entered the studio in 1978 did I understand the importance of my grandpa around the world.”

Balearic house

By the late ’70s, following the death a few years earlier of his great friend and rival, Pablo Picasso, Miró was arguably Spain’s most important living artist. During the ‘20s and ’30s, his poetical, semi-abstract compositions, which appeared so spontaneous, as though dredged from deep within his unconscious, were commonly associated with Surrealism. Yet it was not until after the war that his reputation truly soared, as his influence on the younger generation of Abstract-Expressionists in the US became plain to see.

He wanted to be in peace, left alone from museum directors, collectors, dealers and journalists – Joan Punyet Miró

But international acknowledgement as a pioneer of abstraction came with a plague of distractions that got in the way of painting. And so, in 1956, Miró settled permanently on Majorca, encouraged by Pilar Juncosa, his Majorcan wife, as well as by his memories of childhood summers spent on the island. (His mother was Majorcan too.) “He settled down here,” his grandson explains, “because he wanted to be in peace, left alone from museum directors, collectors, dealers and journalists.”

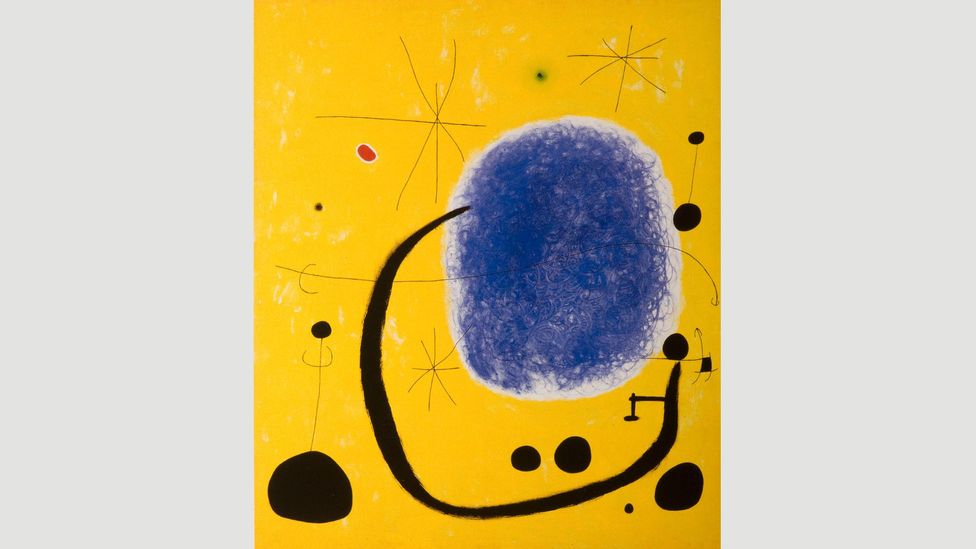

Many of Miró’s paintings like The Gold of the Azure (1968) are bold, colourful and flamboyant – although later works took on a more sombre tone and palette (Credit: Alamy)

In 1981 Miró and his wife established the Pilar and Joan Miró Foundation in Majorca, which preserves the Sert studio. From 21 January, a recreation of the studio, featuring 25 paintings and drawings by the artist as well as pieces of furniture and household items, will be staged by the Barcelona-based Mayoral gallery in a rented space in St James’s in London.

The Foundation in Majorca also looks after a second studio nearby in an 18th Century house that the artist bought in 1959. This handsome building boasts, upon its whitewashed walls, eerie graffiti that Miró executed while planning his sculptures.

Man behind the mask

It also contains, as Joan Punyet showed me recently, the desiccated corpse of an unfortunate cat hanging on the wall of an old-fashioned, rustic kitchen. “My grandfather had a cat,” he explains, “and one day, by accident, he locked the cat inside this house and went away for six months. When he came back, he found this: the terrible, spooky, horrible face of an animal dying of hunger and thirst on the floor. Would you keep this at home? No way! I would throw this in my garbage can immediately, but he kept it in the studio. Why? I think something about the texture and the process of life and death really appealed to him.”

This anecdote about Miró’s cat reminds me of a fundamental contradiction between the artist and his work. In person Miró was orderly and elegant, the epitome of bourgeois propriety. “He dressed like a lawyer or a banker,” Joan Punyet says, “in beautiful suits and handmade shoes. He looked like an English lord.”

André Breton called Miró ‘the most surrealist of us all’

He was also very particular about his working habits: “Every single thing had to be in order: all his brushes and tools were always in the same spot. His methodology was quite strict – that was something I remember about my grandfather. He would wake up at 7am, work downstairs [in the Sert studio] from 9am to 2pm, and then after lunch and a siesta he would answer by himself – because he did not have a secretary – all the letters that he received from people around the world. During the evenings, he would read poetry, sketch, and listen to music.”

Yet, at the same time, this man who appeared so controlled and conventional was capable of unleashing upon canvas visions of such ferocious intensity that André Breton, the French founder of Surrealism, once called him “the most surrealist of us all”.

Picasso was a volcano on the outside, Miró a volcano on the inside – Joan Punyet Miró

“The man you met had nothing to do with the artist,” Joan Punyet explains. “He was putting on a mask. But when he was in his studio, he took off the mask and became a wild beast, a sorcerer, the magician of colour.” He pauses. “It is interesting to contrast my grandfather with his good friend Picasso. They were totally different personalities. Picasso was an extrovert, Miró an introvert. Picasso was a volcano on the outside, Miró a volcano on the inside.”

Late eruption

According to Joan Punyet, the extraordinary thing is that the creative “volcano” inside his grandfather erupted with surprising force when he was an old man. “People assumed that my grandfather, as a successful artist, had retired to Majorca in order to wait for death. But he was not afraid of death, he was not afraid of failure. He was afraid of only one thing: repeating himself.”

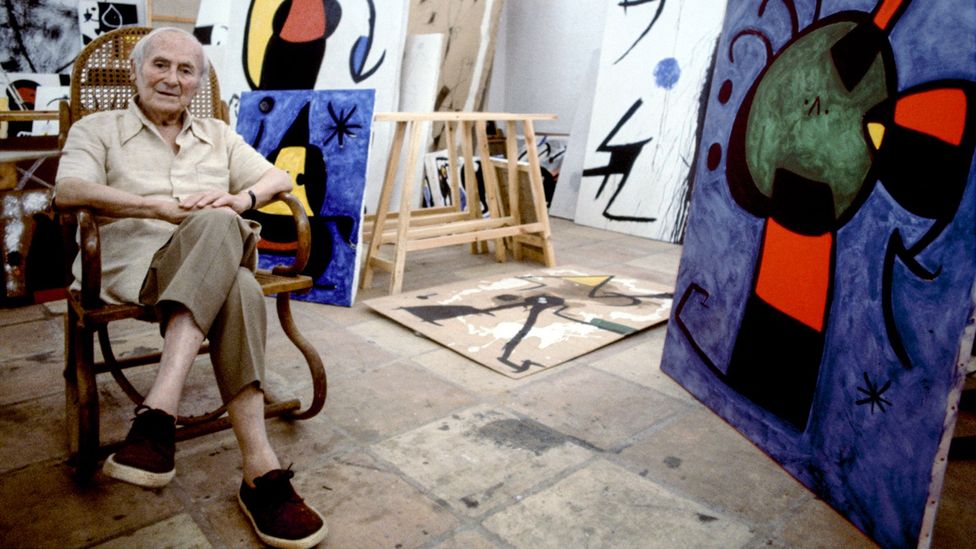

Miró was photographed in his studio by Jean Marie del Moral in 1978, surrounded by works in progress (Credit: Mayoral Gallery)

As a result, in Majorca, Miró reinvented himself as an artist. He did so by, for instance, rejecting colour, which he had mastered as a young man. Instead he started producing brooding, uninhibited paintings full of black that were often thronged with ghouls, demons and monsters. He also worked on canvases placed directly on the studio floor.

“My grandfather said, ‘The older I get, the more violent and expressive I become,’” his grandson says. “In Majorca, he became a new, revolutionary artist: he was walking on a tightrope, taking risks. One day [his dealer] Aimé Maeght came to see him and said, ‘But Joan, your new paintings and sculptures are too radical – how am I going to sell them?’ My grandfather replied: ‘Don’t worry – you just have to wait 35 years.’ And Maeght said: ‘But I’ll be dead by then!’”

When I saw his art, I saw freedom – Joan Punyet Miró

What did Joan Punyet make of his grandfather’s art when he saw it, freshly painted in the studio, on that momentous spring day in 1978? “When I saw his art,” he replies slowly, “I saw freedom. And I couldn’t really match that freedom to his 85-year-old body. It was very strange. How could my grandfather manage to be so childish?”

Today Joan Punyet lives a stone’s throw from the Foundation, in the house where Miró died, aged 90. It is the same property that he visited as a boy when the family gathered on Sunday afternoons for paella. On one occasion he remembers watching his grandfather strip the flesh off a piece of chicken before pocketing the bone. Years later he chanced upon the same bone in the archives of the Foundation: Miró had cast it as part of a bronze sculpture. “I lived the whole process of that sculpture – unbelievable,” Joan Punyet says.

Joan Punyet Miró, the artist’s grandson (pictured here with one of his grandfather’s works) is a poet and performance artist (Credit: DPA/Alamy)

After Sunday lunch, Miró would often play with his grandchildren. Even then, though, he could seem distant. “I was intimidated by him,” Joan Punyet recalls. “I couldn’t chat to him easily. He was often silent – worried about the future of his country. After all, he had lived through the Spanish Civil War, the Second World War, and then 30 years of dictatorship. As a boy, I could feel in him this tremendous energy of despair and worry.”

Yet Miró’s demeanour only enhanced his grandson’s ardent admiration for him. “For me,” Joan Punyet says, “he was a giant. Even when he was walking in the house, I could hear his footsteps, and already I would be impressed by his approach. He left behind a tremendous fingerprint on my spirit.”

Alastair Sooke is art critic of The Daily Telegraph.

If you would like to comment on this story or anything else you have seen on BBC Culture, head over to our Facebook page or message us on Twitter.