What does Gaddafi's death mean for Africa?

- Published

- comments

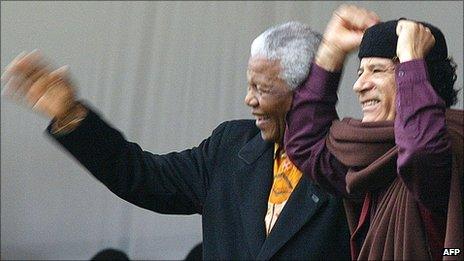

A grandson of Nelson Mandela is named Gadaffi - a sign of how popular the late Libyan leader Muammar Gaddafi once was in South Africa and many other African countries.

With his image of a revolutionary, Col Gaddafi inspired South Africans to fight for their liberation, funding and arming the anti-apartheid movement as it fought white minority rule.

However, he also backed notorious rebel groups in Liberia and Sierra Leone and his demise could serve as a warning to the continent's other "big-man" rulers.

After Mr Mandela became South Africa's first black president in 1994, he rejected pressure from Western leaders - including then-US President Bill Clinton - to sever ties with Col Gaddafi, who bankrolled his election campaign.

"Those who feel irritated by our friendship with President Gaddafi can go jump in the pool," he said.

Instead, Mr Mandela played a key role in ending Col Gaddafi's pariah status in the West by brokering a deal with the UK over the 1988 Lockerbie bombing.

It led to Col Gaddafi handing over Abdelbaset Ali Mohmed al-Megrahi for trial in Scotland. He was convicted in 2001, before being released eight years later on compassionate grounds - a decision Mr Mandela welcomed.

Mr Mandela saw the Lockerbie deal as one of his biggest foreign policy achievements.

"No-one can deny that the friendship and trust between South Africa and Libya played a significant part in arriving at this solution... It vindicates our view that talking to one another and searching for peaceful solutions remain the surest way to resolve differences and advance peace and progress in the world," he said in 1999, as he approached the end of his presidency.

"It was pure expediency to call on democratic South Africa to turn its back on Libya and [Col] Gaddafi, who had assisted us in obtaining democracy."

'Vanquished'

Col Gaddafi's position in Africa was paradoxical. Just as he backed pro-democracy causes, he also fuelled rebellions in countries such as Liberia and Sierra Leone and supported Uganda's infamous dictator Idi Amin.

African leaders tended to overlook this.

"Muammar Gaddafi, whatever his faults, is a true nationalist. I prefer nationalists to puppets of foreign interests," Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni said in February.

"Therefore, the independent-minded Gaddafi had some positive contribution to Libya, I believe, as well as Africa and the Third World.

"We should also remember, as part of that independent-mindedness, he expelled British and American military bases from Libya [after he took power]," Mr Museveni said.

Col Gaddafi played a prominent role in the formation of the African Union (AU) - a body in which he wielded enormous influence because he was one of its major financiers.

At an AU summit in 2008, he got many African traditional leaders to declare him the continent's "king of kings".

A spokesman for one of those traditional leaders - Uganda's Tooro kingdom - says Col Gaddafi was a "visionary" and would be missed.

"We saw the human side of him - not Gaddafi the colonel or the proverbial terrorist as the Americans and Europeans described him," Philip Winyi said.

"In spite of what many see as his weaknesses, he has done quite a lot for Africa, contributing to the building of infrastructure."

Col Gaddafi pushed for a United States of Africa to rival the US and the European Union (EU).

"We want an African military to defend Africa. We want a single currency. We want one African passport," he said.

Africa's other leaders paid lip-service to achieving this vision but none seemed very serious about putting it into practice.

In a BBC interview after Col Gaddafi's death, Kenya's Foreign Minister Moses Wetangula said the late Libyan leader sometimes showed a violent streak at AU meetings.

"He really suppressed Libyan people and vanquished them to the extent that in one of many AU meetings we saw him slap his foreign minister in our presence, which is something unexpected of any dignified and self-respecting head of state," Mr Wetangula told the BBC's Focus on Africa programme.

Mugabe and Gaddafi

An AU expert with the South African Institute for International Affairs, Kathryn Sturman, says Col Gaddafi's death will have a profound effect on the AU.

"It's the end of an era for the AU. Libya was one of the big five [along with South Africa, Nigeria, Egypt and Algeria] financial contributors of the organisation. It paid 15% [of its budget], and also the membership fees of countries in arrears, like Malawi," Ms Sturman said.

"The new government in Libya is not going to be well disposed to the AU [which opposed the Nato-led intervention in Libya]."

Ms Sturman said that while the AU financial woes may worsen, it may work more effectively in the post-Gaddafi era.

"He was very adamant about pursuing a United States of Africa - and was quite obstructive in attempts to bring about deeper regional integration."

Last week, South Africa's President Jacob Zuma - whose government initially backed Nato intervention, but then denounced it - echoed a similar view in a foreign policy speech.

"Colonel Gaddafi spent a lot of time discussing a unity government for Africa that was impossible to implement now. He was in a hurry for this, possibly because he wanted to head it up himself.

"I had arguments with him about it several times. The AU will work better now without his delaying it and with some members no longer feeling as intimidated by him as they did," the South African president said.

It is an open secret in political circles that some African leaders are also intimated by Zimbabwe's President Robert Mugabe, who remained a staunch ally of Col Gaddafi until his death.

Having spearheaded Zimbabwe's independence struggle, Mr Mugabe - who has been in office since 1980 - portrays the opposition as "puppets" of the West as he tries to hang on to power.

But as Col Gaddafi's fate shows, such rhetoric no longer strikes a chord with most Africans - a point South Africa's Nobel Peace laureate Archbishop Desmond Tutu made when he told the BBC's Focus on Africa programme:

"He [Gaddafi] had this wonderful dream about a United States of Africa - like [Ghana's post-independence leader] Kwame Nkrumah, but I think we are going to remember what happened in the latter days of his rule when he actually bombed his own people."