Why opera was the Netflix of the 19th century

Could you live without your phone? Most of us probably wouldn’t want to these days. In fact, you might be reading this on a phone right now. What about opera – could you manage without that?

No, you didn’t misread the question. You see, opera is one of the reasons you own a phone at all. Dr Flora Willson explains in Opera Across The Waves.

When the telephone was first invented, no-one knew that it would ultimately become a device for making personal voice calls – or that one day, we would be using phones to text or swipe right as we walked along.

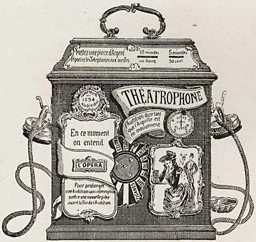

In fact, one of the telephone’s earliest uses was as a revolutionary method of broadcasting opera. A hundred years before online streaming was even thought of, tech-savvy residents of London and Paris could drop into a fashionable café, hotel or club to listen to performances down the line.

As phones gradually became a domestic appliance, the must-have media platform for the home was a subscription to the telephone opera service – the Netflix of its time.

Opera was crucial to the telephone’s early success.

It’s hard to imagine now. These days, opera can seem far removed from the cutting edge of anything. For some, it has a reputation for being conservative, elitist or both: a hangover from the bad old days, c. 1600, when opera was in-house entertainment for Italian aristocrats.

But technology has been helping opera to travel far beyond the opera house for much longer than you might expect. 150 years before YouTube, tunes from the latest operas were heard on street corners, pumped out by barrel organs: semi-automatic music machines whose decibel levels prompted the world’s first anti-noise legislation.

You couldn’t download a new release in the mid-19th century. But you could buy the mass-produced sheet music to play at home (sometimes before the opera had even been staged - piracy has been rife in the music industry from the start).

By the turn of the 20th century, gramophone recordings had transformed opera into a must-have consumer commodity. Arias were the first singles, and opera singers the first recording stars.

Today technology has made opera even more widely available. You can hear opera on the radio, stream it at your desk, listen to a CD in the car or binge-watch clips on your phone. We live in a world where virtually any music is accessible anywhere, any time – and opera is no exception.

Opera made one particularly high-profile move from behind the velvet curtain over a decade ago.

In 2006, Peter Gelb, General Manager at New York’s Metropolitan Opera House, started transmitting performances live to cinemas. His series “The Met: Live in HD” promised audiences a taste of the real, “live” experience, direct from Manhattan – and it was hailed as the dawn of a newly democratic age for opera. Since then, the series has expanded worldwide, now reaching thousands of cinemas in over 70 countries.

So why does opera’s reputation for exclusivity persist? Surely the Met’s move into cinemas signalled some kind of operatic revolution – throwing open the doors of one of opera’s most hallowed venues to all?

The handful of studies on opera in cinemas suggests not. There’s no question that the Met’s programme and others like it help opera reach more people than ever before. But the audiences they reach are very similar to the audiences who attend the opera houses in person: predominantly white, affluent, ageing.

What’s going wrong?

In the digital age, the challenge for opera is not availability. Free opera is already just a click away – if, that is, you want to look for it. And that’s the catch: new audiences simply aren’t looking for it. Opera’s biggest issue today is its own bad reputation – a barrier that can’t be broken down with technology alone.

But reconnecting with opera’s forgotten hi-tech past and reviving its capacity to lead the way in how we produce and consume culture? That might just be the way towards a more genuinely democratic operatic future.

In Opera Across The Waves, Dr Flora Willson traces the roots of today’s cinema broadcasts of opera to the New York of 1890-1930, when the city first emerged as a global operatic centre. Listen live on Radio 3 or online via the Radio 3 website.

-

![]()

Opera across the waves

A fascinating documentary traces opera's adoption of technology through the ages.

-

![]()

Live from the Met

Live performances of the great operas from New York's Metropolitan Opera House.

-

![]()

The woman who loved too much

The tragic tale of Puccini's Madama Butterfly, told in eight pictures from a production at La Scala.

-

![]()

Opera on 3

Browse recent Radio 3 opera broadcasts, synopses and galleries.