America and Russia: Uneasy partners in space

- Published

Space exploration today benefits from collaboration between the United States and Russia. But a history of intense rivalry - in space, as elsewhere - casts long shadows on the relationship.

Since the end of Nasa's space shuttle programme in July 2011, US astronauts have depended on Russian Soyuz flights for transport to reach the International Space Station, an artificial satellite in low-Earth orbit.

As highlighted last week in President Obama's 2012 budget request for Nasa, the US is committed to developing its own systems for crew transportation. But these are not expected for at least five years.

This reliance on crew transportation is "embarrassing", says Prof John Logsdon, a space policy expert on Nasa's Advisory Council.

"It's very hard for the States to maintain its claim to be the leading space country in the world when we cannot even launch people into orbit."

Dr Igor Sutyagin of the Royal United Services Institute says, from a Russian perspective, space exploration today does not have an equal relationship, even though US astronauts rely on their capsules. "Russian astronauts feel like space taxi drivers, not equal partners."

"Russia is losing its position in space because of endless failures of space launches, lost satellites and lost communication. It's humiliating," he adds.

In April 1961, Soviet cosmonaut Yuri Gagarin was the first to orbit the earth. The US followed a year later in February 1962. The space race between the two nations was now well underway.

Despite his ambition to land an American on the moon before the end of the '60s, President John F Kennedy did not want it to be a race.

In September 1963, two months before his assassination, he made a speech before the United Nations General Assembly, and suggested developing a joint mission to the Moon with the Soviet Union.

"Why... should man's first flight to the moon be a matter of national competition? Why should the United States and the Soviet Union, in preparing for such expeditions, become involved in immense duplications of research, construction and expenditures?"

Road to the stars

But Kennedy's proposal to collaborate was shunned by the leader of the Soviet Union, Nikita Khrushchev.

At that time the Soviet Union believed their space programme was ahead of the US, says Dr Sutyagin.

"To agree with Kennedy's proposal would mean to give up the Soviet leadership in reaching the Moon. It was unacceptable from an ideological standpoint.

"Khrushchev wanted to compete and win. He did not want to accept any risks in a joint enterprise with the US."

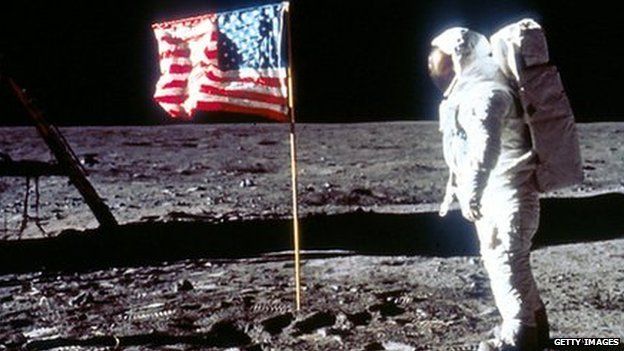

The US "won the space race" when Apollo 11 landed on the moon's surface in 1969, says Prof Logsdon.

But space historian Christopher Riley says that the concept of a race is very Western, and that from Gagarin's pioneering space flight onwards, the Soviet space programme was seen as building a road to the stars rather than running a race.

"Once America had won this 'public' race, the Russians continued to build the road that they'd always intended it to be. They were always in it for the long haul."

After 12 astronauts had landed on the Moon, American politicians lost interest and the Apollo programme was scrapped.

July 1975 marked the first joint US-Soviet space collaboration in the Apollo-Soyuz test flight. A Soviet Soyuz capsule carrying two cosmonauts docked successfully with a US module carrying three astronauts.

This project was instrumental in moving the US and Soviet space-race into a partnership.

"It was like two animals sniffing each other out, realising that they were supposed to cooperate but were not very comfortable doing so, but it worked out," says Prof Logsdon.

Dr Sutyagin says it was the first time that American specialists had a chance to visit the "highly secret installations of the Soviet Space Programme," and that it was the first time the two nations had mutual trust.

"It was the very first example of an open relationship in an extremely sensitive area of space exploration," he adds.

But even though the two nations were working together, they did not share technology, says Prof Logsdon.

"They only shared the information required to accomplish the docking, but the Soviet Union did not give us the design for their space craft and vice versa.

"It was a jointly developed module that both could connect to but the idea of minimal technology sharing was part of the cooperation."

Economic incentive

After Apollo-Soyuz, it was not until the 1990s - after the collapse of the Soviet Union - that the US and Russia worked together again on the space station Mir.

The US then invited Russia to join the International Space Station partnership, but Prof Logsdon says the US took advantage of the difficult economic circumstances Russia was dealing with.

"The US got access to Russian expertise in space flight and early access to the orbiting space station Mir, while the US station was way behind schedule. The US brought Russian expertise and key components into the International Space Station.

"Russia would have preferred to have its own programme but couldn't afford it, so cooperation with America became essential for them."

The Mir collaboration was much more complex than Apollo-Soyuz, requiring technology to be shared to avoid any accidents, as in space "secrets could cost lives," says Dr Riley.

"In forcing two countries to work together, they have to share technology. As soon as these mechanisms are in place, you get greater cultural understanding between countries, which is a far greater prize than any developments in space flight."

President Obama has upgraded the funding for human spaceflight in his 2013 budget request to Nasa but it is not clear if the funding will be granted.

The US is currently developing a powerful new rocket to take astronauts into deep space. There has been no reported international participation in this project.

"They have started a commitment to leaving low-Earth orbit with people. No other countries have made that commitment", says Prof Logsdon.

"It's an opportunity for leadership. No other country can afford to do it on its own, it's not clear if the US can, they may have to enlist partners to make exploration a reality."

But, he adds: "The US has the leading position in manned space exploration."

- Published13 February 2012

- Published14 September 2011

- Published22 July 2011