How cities can become healthy places

- Published

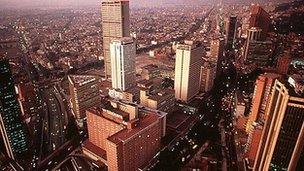

From Monday to Saturday, the streets of the Colombian capital of Bogota are packed with cars.

The city - one of the largest in South America - is a teeming metropolis, home to more than seven million people.

But on a Sunday vehicles are nowhere to be seen. Instead, the streets are taken over by pedestrians, thanks to the traffic-free streets initiative run by the city authorities.

The scheme, backed by successive mayors, has been running in one guise or another since the mid-1970s.

It now covers nearly 100km of roads in the centre of the city on Sundays and public holidays.

But as well as making Bogota a quieter place to roam, the ban on cars also has a health benefit.

Research has shown up to 1.6m residents regularly walk around on a Sunday, with four in 10 out for more than three hours.

For a city where half of people do not take part in the recommended levels of physical activity, the Sunday walk is having a major impact.

It is estimated the ban on private vehicles costs the city $1.7m a year, but this is more than repaid through the health gains, which are estimated to amount to about four times that figure.

The policy has proved so successful that other city governments are looking closely at the Bogota model as a simple and efficient way of promoting health in urban environments.

Dr Julio Davila, a University College London expert in urban planning who used to work in Colombia, says what Bogota has done is a great example of what can be achieved.

"Not all cities naturally lend themselves to walking. It can be expensive or may not be possible to build green spaces.

"But that does not mean people cannot be encouraged to get outside.

"In all this, city governments are crucial. It is the entity which is the closest to people."

But Dr Davila said there are still not enough cities that are making health a priority in the way areas are designed and organised.

Slum conditions

About 3.4 billion people live in urban areas - about half of the world's population.

But an estimated one billion of those live in slum conditions, according to the United Nations.

By 2030 that figure is likely to have doubled unless living conditions improve.

Concern has been mounting so much about the situation that the Lancet medical journal has set up a Commission on Healthy Cities to look at what should be done.

The group has carried out a 19-month investigation, drawing on expertise and evidence from across the world.

Professor Yvonne Rydin, chair of the commission, says there are far too many people still not getting access to basic standards such as clean water and sanitation.

"There has been a widespread failure to address urban health.

"In many areas, rich people and poor people live in different worlds - and the burden of ill-health is highest in the poorest groups."

The commission' s report made a series of recommendations to improve the situation.

It called on city governments to take the lead by working with communities and the private sector to address problems.

It said urban health should be made an intrinsic part of the urban planning process.

To help, the commission published a series of case studies, such as the Bogota one, highlighting what could be achieved.

These include examples of how Western cities are harnessing the latest technologies to design new buildings that promote physical exercise and clean air.

Low tech

But they also involve relatively simple, cheaper projects.

In Mumbai, India, World Bank and government funding has allowed the local community to start building toilet blocks in slum areas.

The aim is to provide one for every 50 people by 2025.

Local people are in charge of the scheme, which has resulted in some of the blocks being developed as community centres for teaching and meetings as well.

Professor Nora Groce, a global health expert who advises bodies such as the World Health Organization and was a member of the Lancet commission, says: "We already know what works - and some of it is low tech.

"It is about having the vision and building the consensus to get things done."

- Published4 May 2012

- Published30 September 2011