New roads bring change and danger to Nepal

- Published

As Nepal and China forge closer relations, new highways are being built between them and, although they may be high, they fail to offer a safer route for drivers or pedestrians.

Nepal used to be the country where everybody walked, from schoolchildren in flip-flops and barefoot porters, to well-shod foreigners like me.

Since the former Maoist rebels formed a government in 2008, however, and started reaching out across the Tibetan border to the Chinese, scores of new roads have been blasted and bulldozed across the Himalayas.

They are transforming the landscape and the lives of the people who live in it.

From my seat on the bus, I was more worried about preserving life than changing it.

I was travelling on the most notorious new road, which forces its way up the Kali Gandaki valley, in the west of Nepal.

This is the deepest gorge in the world... and I seemed to be falling into it.

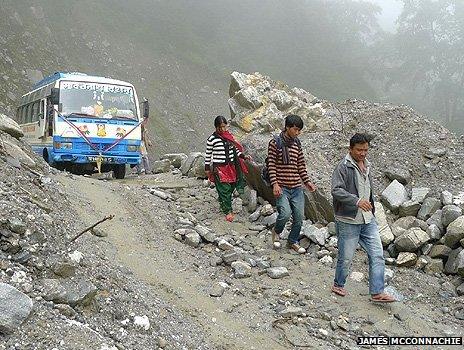

The road had been obliterated by a landslide and, as we lurched on anyhow across a precipitous boulder field, our conductor hung out of the open door to check our wheels did not fall off the edge.

"I want to walk, I want to walk," I found myself muttering. Other passengers were chanting the more conventional Buddhist mantra "Om Mani Padme Hum."

Clutching the arm of my guide, Ramesh Chaudhary, we optimistically leaned away from the precipice.

"This is the worst road I have ever been on," he told me.

This is saying something.

As a trekking guide, Ramesh has travelled all over Nepal. When we first walked in this region together, 15 years ago, just two roads snaked out of Pokhara, the regional capital. Kathmandu, the national capital, had only a couple more.

Half of the country's road networks are regularly made impassable by landslides or a lack of bridges.

Absent tourists

This road was certainly a borderline case. For the British trek leader Ann Foulkes, the journey was "11 of the worst hours of my life".

It was not just the danger that bothered her but the desecration.

"I cried when I saw what they'd done to the valley," she admitted.

The Kali Gandaki trek used to be one of the most celebrated walks in the world.

Pilgrims would toil up to the shrine of Muktinath to pay homage at the natural gas flame there and the holy spring that trickles beneath it. Triumphant hikers would stride down as they concluded the Annapurna Circuit which encircles the vast Himalayan massif at Nepal's heart.

Now, Indian pilgrims were taking what they called the "Muktinath Express" - a piggy-back ride on the back of a motorbike - right up to the shrine.

I met just one pilgrim on foot. As we sat together fighting dizziness at 4,000m (13,000ft), he told me that arriving under his own steam accrued greater spiritual merit.

Actually, he said, "the more you put in, the more you get out."

Tourists, meanwhile, were all but absent.

In Tatopani, a village with hot springs that used to be a honeypot for tired trekkers, I spoke to a pony-tailed guesthouse owner, Bhuwan Ganchan.

As we stood in the street outside his lodge, I could hear the hiss of pressure-cookers making rice, the roar of the river and the occasional clatter of a motorbike on the cobbles.

Tourists were choosing Everest Base Camp, he complained, or other remote regions without roads. "Who flies thousands of miles," he asked me, "to walk beside a highway?"

Other local entrepreneurs were having better luck.

Orchards flourish in the gorge's upper reaches, and almost every passenger on my bus clutched a bag of apples. More, bigger bags, lashed to the roof, were bound for India.

Perhaps Nepal will lose some of the trekkers who support its economy, but it might yet trade its way out of poverty instead.

The greatest transformation, however, is taking place at the far, northern end of the Kali Gandaki road.

The sensitive border with Chinese Tibet is still closed to tourists but every day tractors and four-wheel-drive vehicles bring trailer-loads of Chinese goods.

Political influence pours over the same passes. With the Maoists in government, Nepal is increasingly peering over its Himalayan shoulder into China.

It may yet find its backroads become its escape route from historical domination by India - as long as it can maintain its historic new roads that is.

When we came to a waterfall, and a bridge hanging on one strut, even the fatalistic Nepalese passengers got out and walked - bags of apples and all.

No one seemed too worried. Walking was something they were used to. And until someone fixes the Himalayas, they will likely stay used to it for a good while yet.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 11:30 BST.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 11:00 BST (some weeks only). Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive at the programme website.

- Published19 February 2018