Does medicine really need lab mice?

- Published

These are not ordinary house mice, but laboratory 'mouse models'

Using animals to test drugs destined for humans is controversial, with critics arguing there are other ways to ensure new medicines are safe and effective. But the scientists who carry out the research say animal studies remain necessary.

It is estimated that in the UK around three million mice are being used for research, and tens of millions worldwide.

Despite the difference in external appearances, the genetic similarities with humans are astonishing.

The mouse genome shares over 95% of its genes with humans.

The animal acts as a "model", genetically modified to develop a human disease.

But the use of mice, like any animal, in research is criticised by some.

Animal Defenders International (ADI) is one of the groups that campaigns for an end to the use of animals in research.

"We would argue that animal use is extremely outdated, and not very good science for humans," says Fleur Dawes, of ADI.

The organisation estimates that more than 100 million animals per year are used worldwide for research, about 80% of which are rodents.

Ms Dawes believes the suffering that the animals go through does not justify their contribution to science and medicine for humans.

"There is a big problem with that because there are huge differences between the species. And even though there are similarities with humans and mice, they react very differently to each other when experimented on."

"So what works in one animal is not an indication that that is how things work in other animals."

Alternatives?

However, at the Oxfordshire-based Mary Lyon Centre (MLC), husbandry manager Sara Wells says they are constantly trying to refine the process to minimise the suffering of mice.

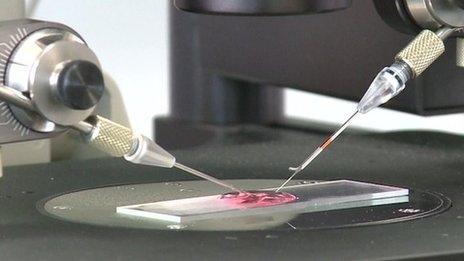

Mice studies can produce carefully controlled data

"If it's a procedure where you can anaesthetise the mice, then you do it to reduce their stress.

"And if there is an alternative method that doesn't involve mice, you are not legally and ethically allowed to do the procedure."

In many countries, including the UK, before trying a new drug on humans it has to be tested first on two different species. Mice are usually the first group of animals.

Once the study has positive results, scientists then jump to other species such as dogs, pigs or primates.

But the ADI considers these are just rules that work as a protective net before a clinical trial is run.

According to the United States' National Institutes of Health, nearly 18 million people are needed for human research.

If we eliminate animal research from the equation, are there alternatives?

Dr Wells says: "There is a massive field developing on alternatives, and we are very supportive of that field and we always keep track of what is going on in that field, because maybe we can replace one of our models."

Those alternatives include chips on human organs to study their function, micro-dosing treatments in humans and computerised models.

"Lots of people say that there is a computer now to model what it is going to happen in diseases," Dr Wells adds. "But we still don't know enough to programme those computers with sufficient knowledge to be able to model what's happening in every disease."

Fleur Dawes agrees one alternative is not enough.

But she says: "By combining the different alternatives, you can actually get a much better picture that is of much better relevance to humans."

- Published28 January 2014

- Published7 February 2014