New Zealand gangs: The Mongrel Mob and other urban outlaws

- Published

New Zealand, a country that routinely tops international lifestyle indexes, may not be the first place you would associate with gang culture - but violent gangs have deep roots in society.

The congregation at St Elizabeth's Church in Clendon, South Auckland, is like no other I've seen in the world. Clutching prayer books in liver-spotted hands are the silver-haired ladies you might expect to see in church on a Sunday morning - but towering over them with menacing tattooed knuckles grasping hymn books are former gang members.

It's not just the swastika tattoos, the missing teeth and scars that make these men - and some women - frightening. The list of serious crimes many of them have been convicted of is also terrifying. And those are just the crimes the police know about.

These people come from outlawed communities, steeped in so much crime that for many, savage beatings, rape and general brutality have been a daily occurrence.

It's a brave old lady that approaches this lot armed with nothing but a Bible and a warm smile.

But it seems that places like St Elizabeth's offer something that some of these gangsters are desperately seeking - community, acceptance and, as with all proselytising faiths, a new beginning.

Jean, a volunteer at the church, helps to support gang members when they get out of jail. "They are terrified of coming out, really scared," she says. "That's why we try and give them wrap-around support, so there is always someone there for them."

New Zealand's gangs rarely make it into the tourist guide books, and are easily avoided by mainstream Kiwis enjoying the kind of existence that keeps the country at the top of the world's lifestyle indexes. Many countries have gangs of one sort or another, but in New Zealand there is a whole subculture.

Gang membership isn't restricted to youngsters with a few years to misspend before growing out of bad behaviour - gangs here are a lifestyle, once joined very difficult to leave, and they hold entire communities in their grip for generations.

There are thought to be more than 40 different street gangs in New Zealand. One estimate from the police association puts the number of full members at 6,000 with a further 66,000 "associate members" - partners and other family members involved in gang behaviour. That's within a population of just four million.

The gangs came into existence in the 1950s and 60s when thousands left the vast rural areas for the cities looking for a better life, and many didn't find it.

Maoris and Pacific Islanders often struggled in the urban scene. Uprooted from their communities, short of cash, and sometimes dependent on alcohol or drugs, many teenagers found the kinship and protection they missed at home in the tattooed, leather-clad arms of the gangs.

Part of the initiation to be accepted as a full gang member traditionally involves committing a serious crime - which explains the high percentage of gangsters in jail. Around 40% of inmates at Springhill prison, south of Auckland, are in a gang. And integration manager Gerry Smith says getting out of a gang is very difficult.

"Some gangs you'll have to pay money to get out, or commit a crime," he says.

"Others you'll get a beating from a pack of other gang members. We're not just talking a slap on the face or a punch on the nose, it could involve stabbing - it's serious assault.

"You have to undergo some formal punishment before you'll be allowed to leave a gang."

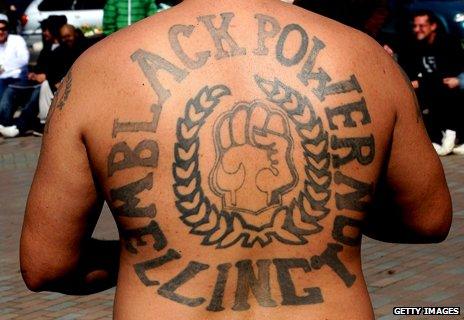

Wherever there are gangs, there is also gang rivalry. Pitched battles in the streets between two of the largest, the Mongrel Mob and Black Power, have been a weekly occurrence in some areas. But there are signs now that some branches of these nationwide gangs are trying to reform from within.

Eugene Ryder, a member of Black Power in Wellington, is one of a number of older members who want to steer youngsters away from a life of crime. He argues that social policy in the 60s and 70s discriminated against Maori children, who were far more likely to be institutionalised for bad behaviour than their European counterparts.

Even today, only 15% of the New Zealand population are Maori or Pacific islanders, but they represent around 50% of the prison population.

Ryder himself has 48 convictions, and was a teenager when he first went to jail. Three of his siblings and his father were already serving time - later his mother would follow. He says that, like many older members, he wants a better life for his own children.

"When members joined the Black Power, the dreams they had for their sons would be that he would grow up with a bottle of whisky in one hand and a gun in the other - now that kid is 18 and his dad has changed his mind.

"We know where that behaviour leads and that's prison, and we don't want that for our children. We've done that, and it's not a good place for them to be. We want to change that."

Ryder says he'll never leave the Black Power as it's become his family, but he wants to encourage more "positive behaviour" as he puts it. He's even been working with the senior members of arch-rivals, the Mongrel Mob, to try to heal some of the old rifts.

But it's a tough job to try to rebrand the gangs that have terrified New Zealanders for so long. And there is another problem. New youth gangs have sprung up and taken over the streets in some areas, inspired by LA-style gangs, rap music, flashy jewellery and expensive cars.

Unlike the "traditional" gangs, there isn't such a sophisticated command structure, but the crimes they commit are every bit as worrying as those of the established gangs - aggravated robbery, drugs, intimidation and, at times, extreme violence.

"Potentially these gangs could be much worse than the gangs we've seen in the past," says sociologist Dr Jarrod Gilbert of the University of Canterbury.

"They haven't given up on society's goals. They want the trappings of success, the bling, the cars and fancy clothes, but their means to achieve that legitimately are blocked, and that leads inevitably to more profit-driven crime."

Rebecca Kesby's Assignment will be broadcast on the BBC World Service on 27 September 2012. Listen to the Assignment via iplayer or browse the documentary podcast archive.