Carrots, sticks and banks

- Published

- comments

One of the fault lines in the coalition has for some time been over the extent to which banks should be compelled to lend, especially to small businesses, rather than just being encourage to do so.

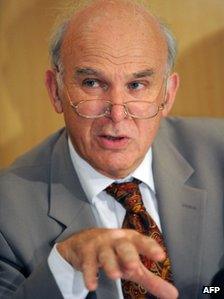

My understanding is that Vince Cable, the Business Secretary, remains concerned that the UK's economic recovery will remain insipid for months and years, unless and until banks provide the credit required by growing businesses.

He has long seen the case for the government to use Royal Bank of Scotland, in which taxpayers have a stake of greater than 80%, as an instrument of policy. This would involve forcing RBS to fill the gaps in credit provision in the UK.

On Cable's analysis, Royal Bank of Scotland has the capital and liquidity to provide loans needed by the kind of businesses that must thrive for positive momentum in the private sector to be established. What RBS lacks is the appetite for risk.

Nor, should I say, is Cable a lone voice on all of this. In recent months, similar concerns have been raised with me on the refusal of banks to provide credit where it is badly needed by senior executives at the Bank of England and the Financial Services Authority.

However, as of this moment, the government and Bank of England have eschewed the stick in their relations with banks and are instead dangling what the hope will be seen as a plump delicious carrot. The Bank of England is providing cheap loans to banks, under the Funding for Lending Scheme, on the condition that the banks do not reduce credit provision to British households and businesses.

And the FSA is trying to reinforce the impact of all of this by saying that there will be no incremental capital charge on banks that make net new loans to the British economy.

Will it work? It is too early to say - and latest data continues to show that money is tight for businesses.

There are two reasons to be cautious: first, it may well be that banks reluctance to lend is mostly to do with the attached risks, and not the interest or capital costs of making the loans; second, banks have a well-documented history of cynically manipulating the rules attached to schemes such as Funding for Lending, by (for example) increasing the categories of loan nominally favoured by the authorities while simultaneously cutting back on other categories of lending - which can result in unforeseen negative consequences.

All of which is to say that it is certainly too early for the board of Royal Bank of Scotland to be wholly confident that it is on a smooth glide path over the next two to five years to privatisation.

If credit provision remains anaemic, if this recession were to look like a three-humped camel with a further dip in the new year, then voices both within the coalition and without would start clamouring for RBS to become a more explicit instrument of the state - such that RBS would be mandated to increase its tolerance of the risk of lending to wealth-creating businesses.

PS The prime minister has today thrown his weight behind an initiative that began in Cable's Business Department, to accelerate small business's access to the money they are owed by their big-company customers.

In Downing Street today, he is gathering together more than 40 of the UK's biggest businesses, to persuade them to provide administrative help to their small suppliers such that their these suppliers can raise cheap short-term loans from banks against the security of approved invoices.

Here's how to think about this: if small businesses are owed money by a huge company like Tesco, their banks know that Tesco is good for the money; so the banks would provide cheap loans to those businesses, so long as Tesco has a system for authenticating what it owes these businesses.

In theory, say officials, supply-chain finance of this sort could accelerate small businesses access to £20bn of cash - and could reduce these businesses reliance on more expensive bank funding.

But, to be clear, this would be useful a one-time boost to the cash flow of businesses, rather than a self-reinforcing dynamic process of increasing the supply of credit (see my post How business can bypass banks for more on this).

David Cameron is trying to set an example, by implementing the scheme in relation to what the state buys from small pharmacies - which apparently could free £800m for these pharmacies.

UPDATE 10:45 BST

A former banker who is advising David Cameron on his supply-chain-finance initiative has rung to tell me I have understated its potential benefits.

He believes the effects will be more dynamic, less of a one-off, than I suggest, by cutting the cost of finance for small companies and releasing incremental credit not currently available from traditional invoice-discounting and factoring schemes.

I presume we all hope he is right.