'Wall of shame' symbolises China's corruption woes

- Published

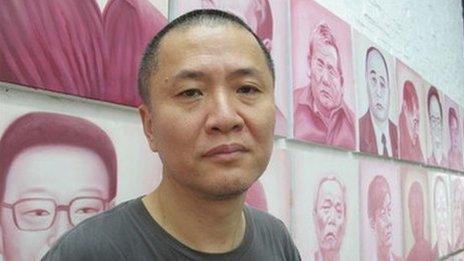

It is China's wall of shame - dozens of portraits of officials jailed for corruption in recent years.

They are all painted in a rosy pink, the colour of China's 100 yuan bill as a symbol of corruption, and hang on the wall of a small studio in Beijing.

The artist, Zhang Bingjian, says he began the project three years ago after watching a report on Chinese state TV about officials taking bribes.

He said he was angered about the level of corruption.

"Without money in China, you are going to have a problem," he said. "People have lost faith. They don't believe in anything but money. Money talks here."

1,600 portraits

Mr Zhang employs several assistants, who scour the internet looking for cases when officials have been jailed for corruption.

Since the project began, Mr Zhang says he has commissioned over 1,600 portraits, and there appears to be no end in sight.

China's next generation of leaders will start assuming power at the 18th Party Congress next month.

Growing public anger over official corruption will pose one of their greatest challenges during the next decade.

The scale of the problem is stunning.

Last year, the People's Bank of China mistakenly released a report on its website which was then quickly taken down.

The report said that between 16,000 and 18,000 government officials and employees of state-owned enterprises had smuggled more than $120bn (£75bn) overseas between the mid-1990s and 2008.

That works out to more than $6m per official.

Earlier this year, Premier Wen Jiabao warned that corruption was the greatest threat to the rule of the Communist Party.

The Chinese public read headlines about anti-corruption campaigns almost every day.

Last month Bo Xilai, the politician at the heart of China's biggest political scandal in years, was expelled from the Communist Party.

Among the charges he faces are that he took "huge" bribes.

But many Chinese see these types of cases as more to do with political infighting than actually about corruption.

Public accountability

Increasingly however Chinese internet users are playing an active role.

In August, an official was photographed smiling at the scene of a fatal bus accident. Bloggers were infuriated by what they saw as his callousness and started investigating.

Pictures of him were posted at various functions and meetings wearing expensive watches - too expensive to be bought on an official salary.

The authorities later announced that he had been sacked.

While low-level and mid-level officials are often fair game, the finances of top leaders and their families are strictly off-limits to the Chinese media, apart from in a few high-profile cases.

In a system where officials are only accountable to the party and not to the public, it is very hard to see how corruption can be rooted out.

"It's impossible to tackle corruption within the system without having independent bodies," said Hong-Kong-based China analyst, Willy Lam.

"Top officials have stopped investigations and refuse calls for other senior officials to publish the assets of their families."

'No choice'

Many of the thousands of incidents of unrest in China every month have their roots in corruption - such as land deals by local officials.

Mr Lam believes that unless China's leaders make meaningful political reforms, they will face "rising social unrest".

In a society where corruption is rife, many Chinese have come to accept it as part of daily life. They know they will often have to pay bribes to get good medical treatment or win lawsuits in the courts.

Chen Wei wants her five-year-old son, Lu Siyuan, to go to a good state school in Beijing.

But in order to ensure a place for him, she says that she would have to pay more than $10,000 in bribes to education officials.

"This is the cost we face," she said. "We have no choice."

Like many here, Ms Chen wants China's new generation of leaders to tackle corruption.

If they do not, they will be storing up trouble for the future.

- Published30 September 2012

- Published13 July 2012

- Published13 July 2012

- Published16 April 2012