Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui acquittal puts pressure on ICC

- Published

The acquittal of former Congolese militia leader Mathieu Ngudjolo Chui by the International Criminal Court has once again mired the court in controversy. Legal expert Jon Silverman considers the options for reforming the court.

Since its inception, the International Criminal Court (ICC) has faced criticism, sometimes over the sluggish pace of indictments and prosecutions, sometimes over its cost, and regularly over its exclusive focus on African crimes.

But it is notable that, in its 10th year, it is the court's existence in its current form which is being subjected to analysis - and the most cogent arguments are coming from exponents of international justice.

Underlying much of the comment is the acknowledgement that, unlike the ad hoc tribunals for former Yugoslavia (ICTY) and Rwanda, which were set up after the event, the ICC is dealing with the contemporary politics of states where crimes have been committed.

In other words, it is much easier to level the accusation that, when the ICC prosecutor unseals an indictment, it is a sign of "victor's justice" being applied.

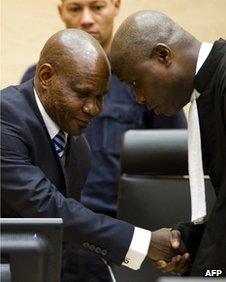

For example, the prosecution of Jean-Pierre Bemba, former vice-president of Democratic Republic of Congo, removed a serious rival to current President Joseph Kabila, in whom the international community has invested some faith.

'Panoply of self-importance'

A former prosecutor at the ICTY, Sir Geoffrey Nice QC, asks whether the ICC has shown itself to be vulnerable to political influences and whether it contributes to the politics of regime change and even risks involvement in ongoing conflicts.

He suggests that recently installed chief prosecutor Fatou Bensouda, the first African to hold the post, should review all current cases, in view of some of the mistakes made by her predecessor, Luis Moreno Ocampo.

Among them, Mr Nice counts the withholding of evidence from defence teams and some apparent sleight of hand over one or two cases that were described as self-referrals by African states but which were probably the result of ICC pressure.

In a recent lecture, the former ICTY prosecutor went further by questioning the "full panoply of importance and self-importance" of the ICC. He criticised the "grand buildings, robes, [and] excessive deference".

He suggested that, instead, ICC judges might profitably spend time in a succession of village halls in Africa to obtain a better understanding of the nature of the evidence they hear.

Toby Cadman, a former senior legal counsel at the Bosnian war crimes chamber, wrote in the Guardian earlier this year in relation to a Kenyan case that he also believes that Bensouda should conduct an urgent review of cases and learn lessons from the Rwanda tribunal, the ICTR, which "successfully fused international legal expertise with appreciation of African dignity".

Too cumbersome?

It has to be said, though, that radical reshaping does not appear to be on the agenda either of the ICC itself or its paymasters, the international community.

The Assembly of States Parties to the Rome Statute, which set up the ICC, recently met in The Hague and agreed to amend the rules of procedure and evidence to achieve greater efficiency.

They also approved a budget for 2013 of 115m euros (£95m).

And the fact that a new headquarters building is slowly taking shape in Scheveningen is a clear indication that the court will remain, in many people's eyes, a symbol of a Western notion of justice.

Perhaps the larger argument is about the ICC as a model for national systems of criminal justice. Is it a shining beacon or a warning ?

Even staunch defenders of international criminal justice, such as Professor Philippe Sands QC, of University College London, agree that there are "questions about processes".

"Are the rules of procedure too cumbersome? Should the indictments be more narrowly drawn," he says.

But on cost, he is dismissive of some of the criticism.

"The costs of the ICC are small compared with the global aid budget, and completely irrelevant as compared with defence spending. You can't compare the cost of international justice with shopping at a supermarket."

Jon Silverman is Professor of Media and Criminal Justice, University of Bedfordshire