Who, What, Why: What is the method for reconstructing Richard III's face?

- Published

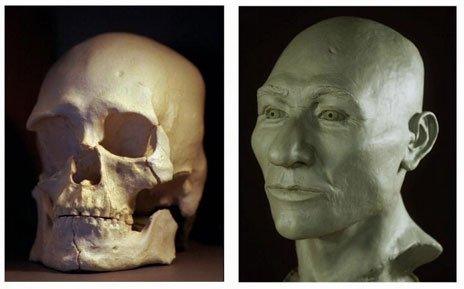

Bones found in a Leicester car park have been confirmed by DNA testing as those of Richard III. But what was the technique scientists used to reconstruct his face?

The only thing scientists had to go on was a skull. No portraits of the king done during his reign survive.

And yet scientists have built a model of Richard III's face. How?

Richard died in 1485 but his bones are well preserved. This doesn't surprise anthropologists as in the right conditions - soil with low acidity and few bugs - bones remain pristine for thousands of years.

The team of scientists at Dundee University doing the facial reconstruction never got near the bones. They were sent CT scans and photographs of the skull, which they ran through a computer programme.

At this point no-one knew if it was Richard III or not, says Caroline Wilkinson, Dundee University's professor of craniofacial identification. It was crucial to ignore any existing preconceptions about what Richard looked like. The shape of the face had to be based entirely on the scans.

It may seem impossible to build someone's cheeks, nose, and eyebrows from a piece of bone. But there are lots of clues, she says. Like teeth.

"The width of the mouth can be determined exactly by the position of the teeth. The little bump on the outer orbit is where the outer corner of the eye is. We can use these anatomical standards to help us rebuild the face."

The nose used to be one of the toughest features to recreate because it's made of cartilage. But recent research has unearthed a formula that allows one to predict what the soft nose would look like from the underlying bone, she says.

Even the shape of the brow can be guessed at, although the number of lines on someone's forehead will not be apparent.

The ears are the hardest thing to get right. All that can be deduced from the skull is whether the person has earlobes and where they sit on the side of the head.

About 70% of the facial surface should have less than 2mm of error, Wilkinson says. One area where they are using guesswork is in the amount of flesh on a 15th Century face. "We use average tissue depth (from today) but he may have been substantially thinner or fatter than contemporary faces."

It took a couple of days to create the digital head. It was then time to build one out of plastic using a rapid prototyping system - essentially a 3D printout.

Prosthetic eyes were made, realistic skin texture created and a plausible wig added. This work was done by the artist Janice Aitken. This stage of the process was guided by posthumous portraits of the king as science draws a blank on Richard's eye colour, skin colour and hairstyle.

Techniques have improved in the last five years because of advances in 3D printing and cheaper access to CT scans. An exhibition in Dresden last year, external recreated faces of hominids dating back millions of years.

The idea of facial sculpture was developed almost 50 years ago by Soviet archaeologist Mikhail Gerasimov, who recreated Tsar Ivan the Terrible, amongst others.

Facial reconstruction is used by criminal investigators to help identify human remains. When all other leads have dried up, it may provide new impetus in an investigation and allow family members of a missing person to rule people in or out.

Martin Evison, director of Northumbria University Centre for Forensic Science says there are limits to what the technology can achieve. "Facial reconstruction can yield a resemblance from the skull, but not an exact likeness. It is not a method of positive identification."

And there can be a danger of giving the subject noble or striking features, says Matthew Skinner, lecturer in anthropology at University College London.

He recalls the Kennewick Man, external, a 10,000-year-old found in Washington State during the 1990s. "They did a facial reconstruction. The result looked remarkably like Patrick Stewart."

Kennewick man: an earlier example of reconstruction

But Skinner says the scientists working on Richard III appear to have been scrupulous in sticking to science. "It looks like they've been unbiased and used very modern techniques to place the muscles and tissues onto the skull."

Wilkinson says she was surprised by how the reconstruction looked. "To have a face developed so similar to the portraits was kind of a surprise."

Richard appears a much younger 32-year-old than the one in the portraits. Facial reconstructions often look young, Wilkinson says. "We can't really add any age creasing as we don't know where to put them."

The youthful result impressed Richard III Society, external member Philippa Langley, who described him as "handsome".

"It doesn't look like the face of a tyrant," she said.

From a scientific perspective the team at Dundee have done a great job, Skinner says. But there will always be an element of subjectivity. "Facial expression is such an important part of how people look. And in the case of reconstruction you have to pick one."

You can follow the Magazine on Twitter, external and on Facebook, external