How Somalia’s al-Shabab militants hone their image

- Published

A recent al-Shabab directive that all its members change their mobile phone numbers shows how tech-savvy the al-Qaeda-linked Somali Islamist group remains and how their communications strategy is key to their survival.

Concerned that their messages may be intercepted, the leadership has also banned members from using smart phones.

The group has long run what is regarded as a slick media machine.

Even without smart phones, it has been known for its sophisticated handling of social media, a reputation at odds with its regular bans on communication technology for Somali citizens.

In particular, it has made extensive use of Twitter in order to get its message across.

It has also devoted considerable resources to producing a series of promotional videos.

Diaspora appeal

Al-Shabab's material aims to spread the group's ideology of establishing an Islamic state in Somalia, in line with al-Qaeda's stated ambition of setting up a global Islamic caliphate.

It wants to achieve this both by military conquest and also the conversion of souls - for which communication technology is a key tool.

Al-Shabab's well-produced video documentaries deliver the jihadi narrative in an appealing form to Somali audiences in the diaspora.

They are aimed at young people of Somali origin such as Hassan Abdi Dhuhulow, a suspect in last year's Westgate mall attack in Kenya. His family is said to have moved to Norway as refugees in 1999.

The group's documentaries are produced by its media arm, the al-Kataib foundation.

Many of them show al-Shabab engaging in charity work and other activities that depict the group as a legitimate authority.

However, they can also be quite gruesome - showing the corpses of those they have killed, including alleged spies who are often beheaded.

And they contain threats to their perceived enemies - in Somalia, neighbouring countries such as Kenya which are helping Somalia's government and the West.

The videos portray al-Shabab's fight as part of a wider global conflict in which Islam is under threat.

English and US accents

Al-Shabab also has its own radio station, Radio Andalus.

The group has acquired half a dozen relay stations, mainly by seizing private radio stations such as HornAfrik, Holy Koran Radio and the Global Broadcasting Corporation radio and their equipment - including some from the BBC.

The website Kismaayo News reported that by 2013, the group had 50 journalists working for Andalus radio.

When it comes to recruiting presenters, al-Shabab is known for its attention to detail.

It generally takes care to use presenters with British or American accents to deliver its English language audio statements.

With statements in Arabic, standard Arabic is used, and the presenters clearly have a high level of education in the language and in Islamic texts.

Swahili-language presenters use classical Kiswahili as spoken in Tanzania and coastal Kenya.

The majority of al-Shabab's audio output, though, is in Somali and is presented articulately and fluently.

Twitter frustrations

A number of pro-al-Shabab websites have emerged, which host material produced by the group and act as vehicles for furthering its military aims.

The content is intended to frustrate efforts by the Somali government and its allies - mainly the African Union forces fighting in Somalia - to eliminate the group.

Al-Shabab has often used Twitter to challenge the veracity of claims made by the African Union forces.

Its Twitter accounts are now closed, but Kenya's military spokesman Maj-Gen Chirchir has continued to attack the group's media policy.

On 20 May he tweeted: "Al Shabaab Courtesy calls! The more videos you release to scare Kenyans the more WE make visitations. Consider peace, the better option."

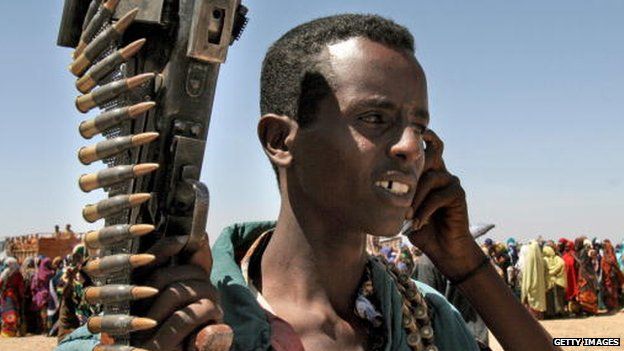

When the group's official spokesman, Sheikh Ali Dheere, appears on video, he is surrounded by fighters.

He reportedly answers to the group's overall leader and oversees a bevy of apparently enthusiastic journalists.

Al-Shabab has honed its media strategy as aggressively as it has enforced its bans on the Somali population.

As the group loses control of parts of the country, it has issued a series of bans on technology:

- Internet: In January 2014, the group declared a ban on using the internet through mobile handsets and fibre optic cables. It said the Muslim population "could be spied on and monitored and information on them transmitted through the internet on their phones". The group also declared that mobile internet devices had "adverse effects on the moral behaviour of the Muslim population in Somalia".

- Smart phones: In 2013 smart phones were banned by the group. Media reports said al-Shabab operatives went round intimidating anyone possessing a smart phone. Their campaign began shortly after a raid on a house in Barawe by US commandos last October. They were targeting al-Shabab commander Abdulkadir Mohamed Abdulkadir, alias Ikrima. He had lived in Norway but returned after failing to get political asylum there.

- TV: In November 2013 the group's members in Barawe announced via loudspeakers that watching television was banned. They declared that it was against Islamic principles and ordered residents to hand their television sets and satellite dishes to al-Shabab officials.

BBC Monitoring reports and analyses news from TV, radio, web and print media around the world. For more reports from BBC Monitoring, click here. You can follow BBC Monitoring on Twitter and Facebook.