US election: How can it cost $6bn?

- Published

The estimated price tag for the US elections in November is almost $6bn (£3.8bn). Why so much?

"The sky is the limit here," says Michael Toner, former chair of the US Federal Election Commission.

"I don't think you can spend too much."

In a time of general belt-tightening, it may sound like a surprising argument, but Toner believes there should be more - not less - spending on US elections.

Anything that engages voters, and makes them more likely to turn out is, he says, a good thing.

"It's very healthy in terms of American politics… it's a symptom of a very vigorous election season, there's a lot at stake here."

On 6 November, Mitt Romney, the presumptive Republican nominee, is set to challenge Barack Obama for the presidency, and polls suggest the margin between them could be wafer thin.

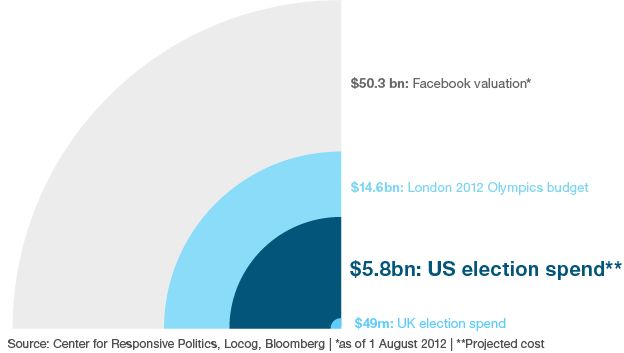

New figures just released by the Center for Responsive Politics, an independent research group which tracks money in politics, estimate the total cost of November's elections (for the presidency, House of Representatives and Senate) will come in at $5.8bn (£3.7bn) - more than the entire annual GDP of Malawi, and up 7% on 2008.

It makes UK election spending look microscopic by comparison. A total of £31m ($49m) was spent by all parties in the last general election in the UK two years ago - making US spending 120 times as much, and 23 times as much per person.

"You could say we've gotten into a crazy world, where the cost of elections has sky-rocketed, and that we are in a wacko world of crazy spending," says Michael Franz, co-director of the Wesleyan Media Project, which tracks political ads.

But, he says, "it all depends what apples and oranges you want to compare".

Franz argues that US elections are "relatively cheap" when compared with spending on, for example, the US military operation in Afghanistan.

Michael Toner has his own favourite analogy: "Americans last year spent over $7bn [£4.5bn] on potato chips - isn't the leader of the free world worth at least that?"

Online campaigning is the biggest area of growth, but it still accounts for a relatively modest amount of money spent.

TV campaign ads reign supreme in the battle for votes (at least in terms of costs), eating up, it is estimated, over half of all campaign spending.

"People are carpet bombed," says Philip Davies, director of the Eccles Centre for American Studies in London.

For some in the battleground states, where ads are most densely targeted, it can get a bit much.

"It's extremely annoying," says Katie Loiselle, a 26-year-old teacher living in Virginia, which used to be a safe win for the Republicans, but is now a crucial swing state.

Loiselle is one of the much-coveted undecided voters. She voted for Obama in 2008, but this time she is not sure.

In theory, she should be a plum candidate for persuasion. In practice, she does all she can to avoid what, over three months before election day, is already starting to feel like an onslaught.

"I'll change my channel when they come on… I might start flipping through a magazine or talking to someone.

"It's not like what they are going to say is going to rouse my intelligence. It just seems they are spending a whole lot of money bashing each other.

"I'm kind of dreading these upcoming months."

It is the presidential debates in October, not the campaign ads, that will help inform her choice, she says.

But for voters like Katie Loiselle, it could be a case of nowhere to run, nowhere to hide. Some experts believe that this year the amount of airspace in key target areas, could - quite literally - run out.

And it is not just the number of ads that is up, the tone has been raised too.

"The negativity is off the charts - 2008 is quaint by comparison. It's approaching two-thirds of all the ads so far," says Michael Franz.

It could hardly be more different in the UK where airtime for campaign ads is free - indeed you not allowed to buy it - and tightly limited.

In the last general election, the two main parties were allowed four or five party political broadcasts each in England, and six between Scotland and Wales - compared to hundreds of thousands of ads in the US.

It is nothing new for a US election to be "the most expensive ever" - there has been a clear and sharp upwards trend for decades.

This time the increase is driven by the Congressional elections. The presidential race itself will cost an estimated $2.5bn (£1.6bn), which is actually slightly down on the 2008 figure of $2.9bn (£1.9bn) - but this time only one party has held primaries to choose their candidate.

And one key factor likely to push spending up is the rise of the relatively new - but already infamous - Super Pacs, which are making their presidential election debut, and can spend as much as they like on political advertising, as long as they do not co-ordinate directly with the campaigns.

They are the "wild cards" in this election (in the words of the Center for Responsive Politics) and predicting how much they will end up spending is next to impossible.

Super Pacs are unpopular with voters, but there seems little chance of getting the rules changed - political spending by corporations and unions was classed as a form of free speech by the Supreme Court in 2010, and is therefore protected under the US Constitution.

Any effort to restrict such spending would, says Michael Toner, probably need a constitutional amendment, and - he says - this would be both "very difficult" and "highly ill-advised".

The US does have a government-run public finance system designed to keep a lid on campaign spending. But both candidates have opted out of it this year, giving them free rein to spend as much as they like.

Obama was the first-ever presidential contender to opt out in 2008, and many experts say the extra money he spent in the final weeks was a significant factor in his victory over John McCain.

But they have to raise it to spend it, and in practice, this means an unrelenting schedule of fundraiser after fundraiser for both Obama and Romney.

Critics say this takes away from the time that candidates spend with the average (not so wealthy) voter, and in the case of a president, risks detracting attention from his day job of running the country.

The media tends to focus on fundraising figures, seeing this as one sign of the overall health of a campaign (Romney outraised Obama by $35m, £22m, in June for example).

But there is a school of thought which says that both money and campaigning matter less than we imagine.

It is the big picture that counts, not the nitty-gritty day-to-day stuff, argues James Campbell, chair of the political science department at the University at Buffalo.

"Every wheeze, misstep or gaffe, every little twist and turn, is heightened for the next day's headlines," he says.

He jokes: "It's like reading a cardiogram and the lines spike up and down, and it's like 'Oh my God, is the patient still alive?'… We are trying to get a bit more perspective."

Campbell, like a number of other political scientists, specialises in predicting election results, and says voters make their choice not so much on campaign ads or electioneering, but based on a few key "fundamentals" - the economy being the most important one.

It is very rare, he says, for a person to change their party affiliation, so the pool of persuadable voters is small, perhaps as little as around 2% or 3% he argues, once you exclude people who will not vote.

But in a close race, tiny margins can be the difference between winning and losing.

"The ads aren't just trying to change the undecided," says Kathleen Hall Jamieson, director of the Annenberg Public Policy Center and author Packaging the Presidency.

"Most of the time, they're trying to mobilise their base."

"Money matters," she says starkly. "You would be giving up the election if you decided to stop advertising."