The underground art rebels of Paris

- Published

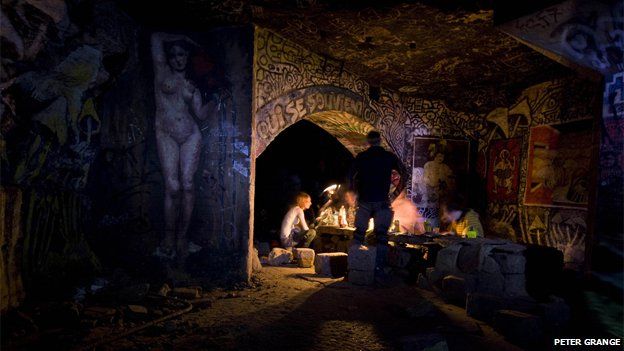

The obsessively secretive members of an underground art collective have spent the last 30 years surreptitiously staging events in tunnels beneath Paris. They say they never ask permission - and never ask for subsidies.

We're standing nervously on the pavement, trying not to feel self-conscious as we furtively scrutinise each passer-by.

After weeks of negotiation, we have a meeting with someone who says he is a member of the highly secretive French artists' collective - UX, as they are known for short - outside a town hall in the south of Paris. It is late on a Sunday night but the street is still quite busy.

Finally I notice a young man dressed entirely in black apart from a red beret and a small rucksack on his back. He hovers for a moment and then motions us to follow him. Our destination is the catacombs, the tunnels that run beneath the pavements of Paris.

A few minutes later Tristan (not his real name) and two companions are pulling the heavy steel cover off a manhole. "Quick, quick," he says, "before the police come."

I stare down a seemingly endless black hole before stepping gingerly on to a rusty ladder and start to clamber down.

There are several more ladders after that before we finally reach the bottom. To my great relief, there are no rats - we go deeper than the rats ever do - but it is pitch black and very wet.

The water is ankle deep and my shoes are soaked through. "It's fine, if you're properly dressed," laughs Tristan as he splashes ahead in his rubber boots.

Using the flashlight on my phone, we do our best to follow him. Along the way I notice some colourful graffiti and a painting of an evil looking cat.

After a few minutes, we reach a dry, open space with intricate carvings on the wall and it is here that we finally sit down to interrogate our mysterious companions.

Tristan explains that he gets a kick out of getting to places, which are normally off-limits. He is a "cataphile" - somebody who loves to roam the catacombs of Paris.

He also climbs on the roofs of churches. "You get a great view of the city, especially at night and it's a cool place for a picnic," he says.

Tristan who is originally from Lyon says his group is called the Lyonnaise des Os - a reference to the piles of bones ("os" is French for "bone") in the catacombs - but also a pun on France's famous water company, Lyonnaise des Eaux. He and his group spend their time exploring the tunnels, and carving sculptures.

The UX are a loose collective of people from a variety of backgrounds. Not just artists but also engineers, civil servants, lawyers and even a state prosecutor. They divide into different groups depending on their interests.

The Untergunther specialise in clandestine acts of restoration of parts of France's heritage which they believe the state has neglected. There is also an all-women group, nicknamed The Mouse House, who are experts at infiltration.

Another group, called La Mexicaine de Perforation, or The Mexican Consolidated Drilling Authority, stages arts events like film festivals underground. They once created an entire cinema under the Palais de Chaillot, by the Trocadero, with seats cut out of the rock.

"Why Mexican? And why does the restoration group have a German name?" I later ask the group's official spokesman Lazar Kuntsmann - (another pseudonym).

"That's just the way it is," he says. "I mean why is Dorothy's dog called Toto? We just like making up nonsensical names."

UX is so secretive, it is hard to define. Tristan says it is "a heterogeneous grouping of diverse informal entities... more a sort of collective phantasm than a real group".

But Lazar Kuntsmann bitterly disputes this. He denies any connection with Tristan's group, who he dismisses as mere cataphiles.

Paris has an unrivalled network of underground tunnels. The city itself was built by quarrying limestone from the soil underneath the buildings themselves, so there are hundreds of miles of quarry tunnels alone.

Add to that all tunnels used for the underground metro system, telephone cables, sewers and so forth and you can travel around the entire city without ever seeing daylight.

The founding members of UX met at a secondary school on the Left Bank of Paris in the early 1980s. At first it was just a bunch of kids who liked breaking into museums and national monuments via underground tunnels, just to see if they could. Video editor Lazar Kuntsmann was one of them.

"As we grew up we pursued our different careers on the surface - everything that's outside UX we call 'the surface'," he explains.

"We have two important founding principles. Firstly we never ask permission - we never consult or inform the authorities about our work - and, of course, we never ask them for subsidies."

Jon Lackman, one of the first foreign journalists to write about UX, compared them in Wired magazine to computer hackers.

"They decided that if they wanted to hold a film festival or a theatre production underground, they would not ask for permission but simply commandeer the resources," Lackman says.

"They get their hands dirty learning how to do things like wire a space, introduce internet, introduce electricity, in order to stage primarily artistic events."

One of UX's most famous acts, six years ago, was restoring a broken 19th Century clock in the Pantheon - the Parisian monument where France's most revered citizens are buried.

A team of eight restorers led by founding member Jean Baptiste Viot, a professional clockmaker, built a secret workshop and camouflaged it behind a stores cupboard. They worked every night for months on the project.

"I was shocked that a clock in an important state building had stopped and nobody had done anything about it," explains Viot. "It is a public service after all."

After the job was complete, they informed the director of the monument who was initially quite grateful. His bosses thought otherwise. They dismantled the clock and attempted to sue UX for 43,800 euros (£35,000, $56,000).

The case was thrown out of court because France has no law against trespassing on or improving public property.

"I think the easiest explanation for the government's behaviour is that they were embarrassed when word got out that their building, the Pantheon, was so easily infiltrated, and that the antiquities within the Pantheon were not being cared for properly," says Lazar Kuntsmann.

Kuntsmann, for his part, once staged a play in the Pantheon at night.

Wired journalist Jon Lackman says that although UX are extremely innovative, they cannot be called revolutionary.

"There is something almost touching about how much affection they have for a 19th Century clock that was falling apart.

"Their urge to conserve is an impulse that one doesn't often see among people who have very innovative, artistic inclinations."

Listen again to On the French Fringe via the BBC Radio 4 website.