We live 'longer but sicker' as chronic diseases rise

- Published

People around the world are living longer but with higher levels of sickness, according to the largest ever study of the global burden of disease.

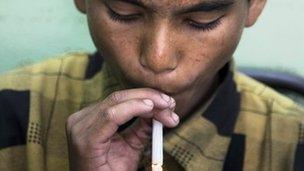

The Lancet analysis shows high blood pressure, smoking and drinking alcohol have become the highest risk factors for ill health.

They replace child malnourishment, which topped the list in 1990.

But some researchers have criticised the way the data was put together, and suggested it is based on poor evidence.

The five-year project, involving almost 500 authors, found heart disease and stroke caused around one in four deaths - almost 13 million - worldwide in 2010.

The burden of HIV/Aids remains high - accounting for 1.5 million deaths that year.

While the age people can expect to live to has increased around the world, the gap in life expectancy between countries with the highest and lowest figures was broadly unchanged since 1970.

Sub-Saharan Africa continues to have a high rate of early death.

Prof Christopher Murray, from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation (IHME) at the University of Washington, led the work.

He said: "There's been a progressive shift from early death to chronic disability.

"What ails you isn't necessarily what kills you."

'Controversial judgements'

Diseases such as diabetes and lung cancer moved up the rankings, while diarrhoea and tuberculosis moved down.

The researchers said deaths from diarrhoea have declined by 60% in the past 20 years, although some scientists feel the disease toll from poor sanitation has been under-estimated.

Prof Sandy Cairncross, from the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM), said in an Lancet editorial: "The complexities of the task have been compounded by inadequate consultation.

"Although the findings portray the work of numerous experts, the rankings made do not show the scientific consensus of all those involved."

He told the BBC that some "controversial judgement calls" had been made about the strength of evidence.

However, the project was welcomed by the LSHTM's director, Professor Peter Piot, who said the work showed how "surprisingly fast" the world's health problems were changing.

He said: "It also shows and recognises the fantastic progress that's been made on the health issues which are part of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs).

"Promising to cut deaths among mothers and infants, for example, has helped to concentrate minds and resources.

"This is relevant to the current discussion about the new series of MDGs which will go beyond 2015.

"I'm very concerned there's a trend to talk about dropping the current MDGs and replacing them with something more vague such as 'sustainable development'.

"I think it would be a disaster to drop our focus now. "