Jim Mortram's Small Town Inertia

- Published

- comments

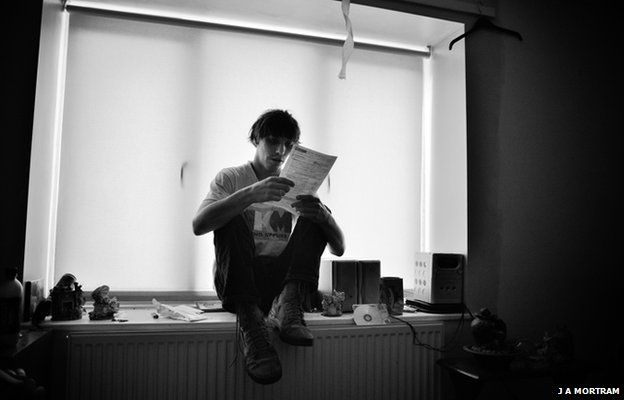

It is often said that you do not need to travel to the ends of the earth to find a good story. One person who has proved that is Jim Mortram, whose documentary work has been creating something of a stir online.

His project, Small Town Inertia, is shot close to home in East Anglia and comprises intimate portraits firmly rooted in the documentary tradition, accompanied by the subject's story in their own words.

The stories are sometimes moving, often challenging and always compelling.

"I'm a carer in my family home, looking after my mother who suffers from chronic epilepsy." Jim says.

"I have been influenced by my upbringing in an environment that has both advocated and required empathy and patience. Also, living on the fringe of society, as a direct result of the situation, has given me a certain perspective on many elements of life.

"For example, the way people perceive the disabled, those with less financial security and to some extent the class system. I can see how frustrating it can be for people who are judged, stereotyped and misrepresented in both life, and to some extent, the media, and have no opportunity to answer or fight back."

In the early days Jim borrowed a camera and his determination to tell stories meant he was drawn to documentary work, offering those who do not have a voice a chance to express their own views. Using social media Jim managed to draw support from a wide number of photographers who offered equipment and advice.

The pictures are undeniably powerful and it is wonderful to see straight photographs that look like real pictures and are of the real world. Yet their power lies in the stories and in Jim's ability to draw those out. So, I thought to echo that, the only way to present this is in Jim's own words.

Jim Mortram

My work is all about acknowledgement, listening and sharing. The photographs are a by-product of those initial elements. This series is rooted in my community, mainly because of my work at home as a carer, and the time, financial and geographical restrictions that imposes.

But the outcome of those restrictions has really been of benefit as it has connected me with my community in a very real way. I do feel that we all exist globally as one vast network of people, all with stories, experiences, lives, obstacles and joys, so this series could work in any place.

My approach has always been the same. I meet someone, we talk and I ask if they might like to share their story. We progress from there. Sometimes this happens very fast and I might shoot then and there. Sometimes it might take a few years for the trust to evolve, and that trust is key. Without it I would be photographing people who are scared of the camera and it is part of my job to make the camera invisible.

I don't want the camera to be a barrier between the person pictured and the viewer or to influence what is happening in the shot. Often I'll go on shoots without a camera, maybe just a digital recorder, listening and talking. Trust is the foundation of everything.

The photography comes naturally and is the extension of shutting up and paying attention to the world around us, it is also the perfect vehicle for relaying these stories in our world today.

The role of photography is twofold. Many times I work on stories with people who have no chance to share or to get anything off their chest and have little interaction with anyone. Having a few hours to talk and make some images is a great release, a catharsis. Also, I'm yet to meet someone who really did not have a passion to have their story told, it is always of great importance that someone hears them, sees them and knows they exist.

I hope people looking at the pictures and reading the testimonies will have a greater understanding of the lives around us and will embrace that. It might be the sharing of 2D images but I'm after a 3D reaction and understanding from the audience.

The series is totally open-ended and the basic rules are applicable anywhere. Anyone, regardless of community, culture or social standing is a potential subject. More than geographical confines I see the project as relating human experience and endurance, so even if the series in the current location were ever to cease, I'd continue this work.

Ultimately it is all about people, that is - the person the "other" side of the lens. I'm not projecting myself in to these images. My job is to to be quiet, to listen and to see, without adding visual parlour tricks or giving a hard-sell to an audience potentially saturated by digitally enhanced emotions. I intend the images to be as honest as the people sharing their stories.

Everything is the sum of its parts. I'm a product of the life I have had, photography is an extension of me and thus the resulting work is a product of that. We are all, to lesser or greater extent, a product of our environments and experiences even if it's a reaction against or assimilation within them. So I very much see my work as a result of both my life and of those within the work.

You can see the full stories on Jim Mortram's website, Small Town Inertia. Jim is also part of the Aletheia Photo Collective and you can follow him on Twitter.