Can biology explain the global credit crunch?

- Published

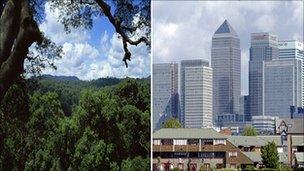

Biology and the natural world are helping economists build new models to understand the dynamics of the financial sector and why the US sub prime loan crisis caused so much global damage.

Could an understanding of ecology have helped prevent the credit crunch?

It sounds unlikely, but a group of scientists working with the Bank of England believe banking has lessons to learn from biological science.

"One of the things that's come out of the crisis is that people now have the courage to think out of the box," says Gillian Tett of the Financial Times.

"There's a lot the financial world can learn by looking at other disciplines."

Banking has a long history of borrowing ideas from science - astronomer Edmund Halley was constructing mortality tables for the life assurance industry back in the 17th Century.

But the real wave of scientific input came in the 1970s and 1980s, when computing power began to revolutionise finance.

"You had the technological revolution and at the same time you had growing complexity of finance, and growing demand from investors for an ability to navigate this complex world," says Gillian Tett.

As the financial sector grew, so did the demand for talented, numerate graduates to create new and ever more sophisticated products.

But the financial sector became too tangled and when the crash came, it threatened to bring down whole economies.

"This was not something that our conventional models could make sense of," says Andrew Haldane, executive director of financial stability at the Bank of England.

"Activity in every country around the world fell off a cliff," he says.

Biological systems

But there was one group of people who could make sense of it.

Enter the biologists.

Scientists and the Bank of England have begun to explore possible insights from the life sciences.

Comparisons are being drawn between biological systems, with their complicated webs of interactions between all the different species, and with the interactions between different banks and financial institutions.

"We need to think about the system as a system, rather than looking at this atom by atom, or node by node," says Andrew Haldane, admitting that pre-crisis, this had not been done.

"We didn't differentiate between the big and the small, we didn't really think hard about the joins between them," he says.

Until now, system-wide data collection in banking has been virtually non-existent. Regulators are hoping they can gather information to allow them to map the financial web, and spot fluctuations that could lead to an institution collapsing.

Seeing banking as a biological system can also help explain why the financial world became so vulnerable.

Paradoxically, as banks grew bigger and more complex, the financial system as a whole ended up being more homogeneous.

"It's rational for an individual bank to have sought to diversify its balance sheet," says Haldane.

By taking on different functions, a bank spreads its risk - it is not putting all its eggs in one particular financial basket.

But all the big banks were doing the same thing.

"The quest for diversification by individual banks, led to the system as a whole rather lacking in diversity," Haldane says.

In biological science, a lack of diversity in a population equals a lack of robustness - and this has fuelled calls to break up the big banks following the credit crunch.

Big bank 'disease'

Another approach is to look at the spread of disease through a population by drawing on the parallels between big banks, and the epidemiological concept of a "superspreader" - an individual who, through their contact with large number of other people, is responsible for the spread of an infection.

Like the spread of an infectious or sexually transmitted disease, the crisis that struck the biggest banks had a knock-on effect to the other institutions connected to them.

"For the equivalent of the promiscuous, we have these big banks globally who have interconnections with all the other banks in the system," says Andrew Haldane.

"What you need for those types of entity is a greater amount of protection up front," he says.

In banking terms, that protection requires that the interactions between institutions are kept from being so convoluted that when there is trouble, everything goes wrong at once.

The challenge is how to do that in practice, streamlining interconnections and maintaining diversity.

Among the areas under discussion between banks and regulators is requiring banks to increase the amount of capital they hold as protection against losses.

"This has been a learning experience for all of us," says Haldane.

"Things have happened that people thought couldn't happen, and the quest has been to make sense of them.

"It's been tremendous that others have come along and said look, you might be startled by this, but these sorts of things have been happening in our discipline for a hundred years, here's a way of making sense of it.".

Scientists of the Sub Prime can be heard on BBC Radio 4, on Thursday 17th February at 9pm, or catch up afterwards on BBC iPlayer.