Arsenic-loving bacteria may help in hunt for alien life

- Published

The first organism able to substitute one of the six chemical elements crucial to life has been found.

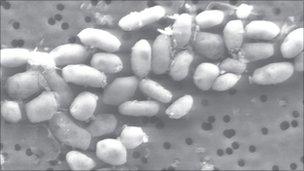

The bacterium, found in a California lake, uses the usually poisonous element arsenic in place of phosphorus.

The find, described in Science, gives weight to the long-standing idea that life on other planets may have a radically different chemical makeup.

It also has implications for the way life arose on Earth - and how many times it may have done so.

The "extremophile" bacteria were found in a briny lake in eastern California in the US.

While bacteria have been found in inhospitable environments and can consume what other life finds poisonous, this bacterial strain has actually taken arsenic on board in its cellular machinery.

Until now, the idea has been that life on Earth must be composed of at least the six elements carbon, hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, sulphur and phosphorus - no example had ever been found that violates this golden rule of biochemistry.

The bacteria were found as part of a hunt for life forms radically different from those we know.

"At the moment we have no idea if life is just a freak, bizarre accident which is confined to Earth or whether it is a natural part of a fundamentally biofriendly universe in which life pops up wherever there are Earth-like conditions," explained Paul Davies, the Arizona State University and Nasa Astrobiology Institute researcher who co-authored the research.

"Although it is fashionable to support the latter view, we have zero evidence in favour of it," he told BBC News.

"If that is the case then life should've started many times on Earth - so perhaps there's a 'shadow biosphere' all around us and we've overlooked it because it doesn't look terribly remarkable."

As unexpected

Proof of that idea could come in the form of organisms on Earth that break the "golden rules" of biochemistry - in effect, finding life that evolved separately from our own lineage.

Study lead author Felisa Wolfe-Simon and her colleagues Professor Davies and Ariel Anbar of Arizona State University initially suggested in a paper an alternative scheme to life as we know it.

Their idea was that there might be life in which the normally poisonous element arsenic (in particular as chemical groups known as arsenates) could work in place of phosphorus and phosphates.

Putting it to the test, the three authors teamed up with a number of collaborators and began to study the bacteria that live in Mono Lake in California, home to arsenic-rich waters.

The researchers began to grow the bacteria in a laboratory on a diet of increasing levels of arsenic, finding to their surprise that the microbes eventually fully took up the element, even incorporating it into the phosphate groups that cling to the bacteria's DNA.

Notably, the research found that the bacteria thrived best in a phosphorus environment.

That probably means that the bacteria, while a striking first for science, are not a sign of a "second genesis" of life on Earth, adapted specifically to work best with arsenic in place of phosphorus.

'Weird branch'

However, Professor Davies said, the fact that an organism that breaks such a perceived cardinal rule of life makes it is a promising step forward.

"This is just a weird branch on the known tree of life," said Professor Davies. "We're interested ultimately in finding a different tree of life... that will be the thing that will have massive implications in the search for life in the Universe.

"The take-home message is: who knows what else is there? We've only scratched the surface of the microbial realm."

John Elliott, a Leeds Metropolitan University researcher who is a veteran of the UK's search for extraterestrial life, called the find a "major discovery".

"It starts to show life can survive outside the traditional truths and universals that we thought you have to use... this is knocking one brick out of that wall," he said.

"The general consensus is that this really could still be an evolutionary adaptation rather than a second genesis. But it's early days, within about the first year of this project; it's certainly one to think on and keep looking for that second genesis, because you've almost immediately found an example of something that's new."

Simon Conway Morris of the University of Cambridge agreed that, whatever its implications for extraterrestrial life, the find was significant for what we understand about life on Earth.

"The bacteria is effectively painted by the investigators into an 'arsenic corner', so what it certainly shows is the astonishing and perhaps under-appreciated versatility of life," he told BBC News.

"It opens some really exciting prospects as to both un-appreciated metabolic versatility... and prompting the questions as to the possible element inventory of remote Earth-like planets".

Steven Benner, an astrobiologist based at the University of Florida took a measured approach to the significance of the find at a press conference held by Nasa on Thursday.

However, he noted that although the conditions on Earth may not have particularly favoured the development of arsenic-based life, that may not be the case elsewhere in the cosmos - or even nearer to home.

"In our Solar System, there are places - Titan, a moon of Saturn, is one of them - where the temperature is much lower," Professor Benner said.

"Where very reactive species like arsenate could very well be useful because although they are too unstable to exist in many environments on Earth, they're not too unstable to exist on Titan, which is at -290F.

"You might very well want to have that increased reactivity just to get the reactions you want and make your biopolymer chains go faster."

Update 10 July 2012: Further research has disputed these findings - more information can be found in an updated story..

- Published16 February 2009

- Published14 August 2008

- Published23 August 2010

- Published6 April 2005

- Published22 September 2004

- Published19 November 2003