Bloodhound diary: The unique challenge

- Published

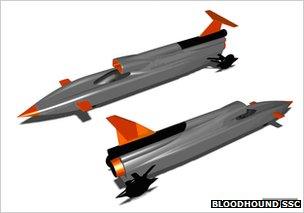

A British team is developing a car that will capable of reaching 1,000mph (1,610km/h).

Powered by a rocket bolted to a Eurofighter-Typhoon jet engine, the Bloodhound SSC (SuperSonic Car) vehicle will mount an assault on the land speed record.

The team behind Bloodhound is writing a diary for the BBC News Website about their experiences. Normally, these entries are written by the driver - RAF fighter pilot Andy Green, the current world land speed record holder.

But this particular diary has been penned by Ron Ayers, Bloodhound's chief aerodynamicist.

Designing a 1,000 mph car is a unique challenge. Where do we start? If we were designing a road car, there would be no such problem.

We would simply study the thousands of road cars already existing to see what works well, and what to avoid.

We would know the safety regulations that we had to satisfy; we could conduct user surveys to determine just what was needed by the target market.

But none of these sources of information is available to the designer of a pioneering project such as a supersonic car.

What should it look like? What currently unforeseeable problems will end up controlling the design?

Where no other guidance exists, the vehicle's design is restricted purely by the basic laws of physics, and by the designer's own imagination.

Faced with unlimited possibilities, where should we - the designers - begin?

With no prior art to guide us, a period of research must precede the actual design. "Suck-it-and-see" designs are sketched, just to find out why they will fail.

Alternative propulsion systems must be considered. Can jet engines alone get us up to 1,000 mph? Would a rocket motor be controllable, and safe?

How can we keep the car on the ground? How do we control it? How do we stop it? What should the wheels be like?

Eventually, a few possible solutions begin to emerge. How about a rocket (for brute force) plus a jet engine (for control and for low speed testing)?

A succession of more detailed designs is tried (we are now on configuration 11!) and ever more issues are identified and resolved.

But all of this takes time, and the amount of time is difficult to forecast because, just when we think all of the problems have been identified and solved, another one rears its ugly head.

However, that phase is finally behind us. We have finished our research. All of the principal features of the car have now been defined, and any more changes to the external geometry will purely be detailed refinements.

In short, Bloodhound SSC is no longer a paper project. Indeed, some components have already been made, and for some months Dr John Davis has conducted extensive dyno cell tests of the Cosworth engine and the HTP (high-test peroxide) pump. This has been a massive body of work, supported by Daniel Jubb and many sponsors, and providing a huge amount of invaluable data.

Manufacture of the auxiliary power unit gearbox is progressing with product sponsors Jaivel and Newburgh Engineering machining the gearbox casing. Once the components are completed, they will be sent to transmission specialist Xtrac, where the gearbox will be assembled and tested.

The design and stressing of the rear sub-frame has also been completed by Brian Coombs and Roland Dennison. This is a substantial, complex and highly stressed component.

Detailed design work has also started on the 500-litre jet-fuel tank. This work is being carried out in conjunction with Advanced Fuel Systems, another product sponsor.

Our progress with designing the composite components has so far been hampered by lack of relevant in-house skills.

Wing Commander Andy Green gives a tour of the Bloodhound SSC model

This has now been rectified by the recruitment of Stuart Allen as our Senior Composites Engineer. Stuart has extensive experience in Formula 1 and Le Mans Sports Car racing. We will be now able to properly engage with UMECO ACG, our composites sponsor.

The Bloodhound team is now routinely employing Additive Manufacture (AM) techniques to make components.

AM creates shapes using three-dimensional printers and can be vastly more economic than machining components from solid metal. It used to be known as Rapid Prototyping, but the technique has now developed to the point where it can be routinely used for component manufacture.

Meanwhile, our education activities continue apace, and some British schools are now expressing an interest in linking up with schools in South Africa.

We are opening a second Bloodhound Education Centres. We have also signed Bits for Bytes as a product sponsor. They have given us seven 3D printers for use in the Education Centres to demonstrate how additive manufacturing works.

The project began with an infinite number of design possibilities. We are now building the car.

Is that the end of the problems? Of course not - the problems of building, testing and operating Bloodhound will continue until it has completed its final run. Meanwhile, you can see the basic logic that has controlled the final shape of Bloodhound on here on BHTV.

- Published10 September 2011

- Published18 May 2011

- Published26 April 2011

- Published5 March 2011

- Published7 February 2011

- Published21 November 2010

- Published13 November 2010