Smashed Hits: What is a Bohemian Rhapsody?

- Published

- comments

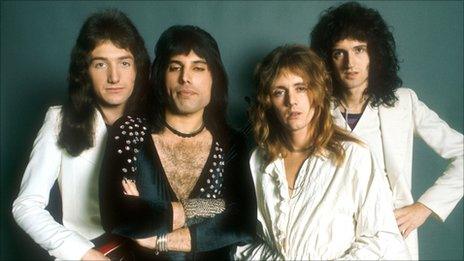

BBC Radio 4's Desert Island Discs listeners have chosen Bohemian Rhapsody as their favourite pop song. It's the only number one about a murder trial to feature both opera and head-banging. But who is Bismillah, asks Alan Connor in his occasional series on song lyrics, Smashed Hits.

Freddie Mercury used a piano as the headboard of his bed. The double-jointed Mercury would awake with inspiration, reach up and back behind his head and play what he'd heard in his dreams. This was how Bohemian Rhapsody began.

Some 20,000 people bought the single every day in its first three weeks, it's been number one twice so far and it's played on a radio somewhere in the world about once an hour. It's also now been chosen as the favourite pop song of Desert Island Discs listeners.

It's no critics' favourite - the Melody Maker dismissed it on release as "Balham Amateur Operatic Society performing The Pirates Of Penzance" - but it was the desert-island pop choice of Jackie Stewart, Anita Dobson and the British public.

So what's going on?

The essential story is not pop's greatest enigma: a man confesses a murder to his mother, vainly pleads poverty in a trial and ends up resigned to his fate. But questions remain: who did he kill and why? And why does the judge talk funny?

Indeed, it's the language in the court scene that arouses most curiosity. There's a touch of Italian culture: Scaramouche is a buffoonish stock character in commedia dell'arte; Galileo was a Florentine astronomer found guilty of heresy by the Inquisition and Figaro is the title character of Rossini's opera The Barber of Seville, in which he helps true love to prevail.

Sticking with Spain, the fandango is a flamenco dance, which had appeared at number one eight years previously in A Whiter Shade Of Pale.

"Mamma mia", of course, means "my mother" in Italian - and was the title of the chart-topper which followed Bohemian Rhapsody - but it's also an exclamation in a moment of high drama. And that's how much of the song works. We don't need to be familiar with 16th-Century Italian theatre to know the "poor boy" is in some pretty serious trouble. The counsel for the defence tries to match the prosecution's ornate flourishes - "spare him his life from this monstrosity" - but it doesn't do much good.

Freddie Mercury, of course, enjoyed ornate language as much as spandex unitards and there's a sense of revelling in sound and phrase.

Senior Lecturer in English at UCL and Queen fan Matthew Beaumont says: "The architecture of Bohemian Rhapsody - and it is an architecture - is self-consciously, ostentatiously baroque. It is rich in ornate, curious details, occasionally Moorish in provenance. Also in soaring, sometimes dizzy-making, shifts of register and in a lachrymose emotiveness that is almost impossible to resist."

It's also impossible to resist seeking something autobiographical in the lyric. Paul Gambaccini told Kirsty Young: "Tim Rice has this theory that it's to do with [Mercury] coming to terms with being gay, and I think there's a lot in that - the resignation, the abandonment of a previous role." The allusions to persecution and secret love in Galileo, Figaro and the rest don't hurt this theory, but not everyone agrees.

In 2004, Queen's Greatest Hits became the first rock album allowed in Iran. The cassette came with an explanatory leaflet which insisted the hero "killed a man" by accident, then sold his soul to the devil. On the night before his execution he calls God in Arabic - "Bismillah" - and so regains his soul from Satan.

Ben Elton has offered a re-interpretation in the musical We Will Rock You, where Scaramouche and Galileo become singing rebels in a future society where rock music has been banned by baddies.

For many listeners, though, Bohemian Rhapsody is "about" sheer sonic bombast, as captured on film in Wayne's World. But its ambition - and its length - were nearly its undoing. Record company EMI was reluctant to release it as a single until the band slipped a copy to DJ Kenny Everett, who played it on Capital Radio 14 times over the following weekend, persuading EMI, the BBC and other sceptics that the listening public could handle it.

Queen also regarded the song as a mini-showcase of their technical skill. "We felt that Bohemian Rhapsody probably captured more or less all the types of moods that we were doing," Mercury told Phonograph Record magazine in 1976. "So we thought: OK, this is what we want to present to the public and let's see what they do with it."

The public's choice of "Bo Rap" as a desert-island favourite is also, perhaps, a vote for kitsch. It's a song about love, loss and death that's undoubtedly silly. "We viewed it quite tongue-in-cheek," Mercury insisted, but that lets you take it to heart as seriously as you like. "It's fairly self-explanatory," drummer Roger Taylor told the BBC, "there's just a bit of nonsense in the middle."

It was also Taylor who made possibly the most inspired decision during the recording sessions. He locked himself in a cupboard until everyone agreed the b-side would be his song I'm In Love With My Car.

Though less celebrated, Taylor's track automatically sold a copy every time someone bought Bohemian Rhapsody - with according royalties.