Tripoli witness: Tribalism and threat of conscription

- Published

A Tripoli resident - who does not want his name to be used for security reasons - describes life in the Libyan capital. He says work, or the lack of it, is becoming a pressing concern for many - and so is the threat of conscription.

You know there is a problem in a country when you find that almost everyone you know is awake until the dawn call to prayer - and afterwards sleeps from sunrise until the early evening before sitting with their families again with nothing much to do.

The exception to the boredom is the still-worrying situation of fuel shortages, and a new phrase - "tribal allegiances" - being hammered out on state television.

The paradoxes of life here are on the rise and it is no longer only through official rhetoric.

In the country that spent decades battling the influence of tribes, there appears to be a concerted effort by the regime to revive their role.

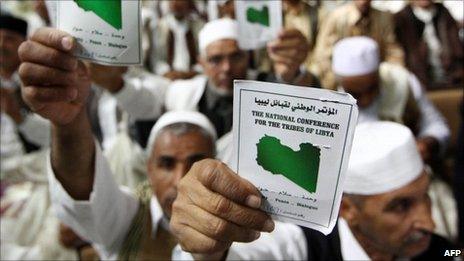

Many watched the national conference of Libyan tribes on state television this week with an inescapable degree of confusion and at times amusement.

They gathered to propose solutions to end the bloodshed, among other aims that were arguably lost through the pro-government rhetoric that dominated the discourse of most speakers.

"Who are these people?" was a common first reaction.

"Since when do we have a national tribal council or whatever they call it and since when do we speak in the name of tribes?" was another.

A common conclusion offered was: "This is it, the regime is sowing the seeds of tribal rivalry, by making them all think that he is giving them power".

Rising unemployment

We all have a lot of time on our hands these days and we spend much of it watching television or discussing what we see on our screens. There is a reason for that.

The closures of foreign companies, along with some well established private local ones, have been problematic for many people.

They now only exist in name and spirit and in most cases with a green flag waving in the gentle breeze on the roof of their headquarters, while armed security agents idly sit outside the gate on a plastic chair, sweating beneath the Sun's rays.

This has significantly increased the already high unemployment rate that existed in the country before the uprising.

It could be argued that the law requiring all foreign companies to employ a majority of Libyans has now paradoxically created more unemployment.

The foreign companies seem unlikely to ever come back or resume activity so long as the regime remains in power - or at least as long as their countries insist they want a change of government.

Tens of thousands of educated men and women found themselves unemployed overnight in the early days of March.

It is perhaps no wonder that many people - particularly in the capital - have been growing increasingly restless.

Dangerous dilemmas

Over in the state-run companies, it is a different story.

There is undoubtedly support for the regime among the ranks of civil servants, the majority of whom have long been employed by the state despite having few qualifications, in an attempt to ease unemployment.

These are the people who stand to lose a lot in the event of the current regime's exit.

There are other civil servants in the capital, however, who are equally adamant that anything less than the complete downfall of the regime is unacceptable.

In late February they stopped going to work - mainly out of fear of what would happen following the anti-government protests.

"We were contacted by our bosses insisting we come back to work," someone who works for a state-run company told a friend of mine recently.

"They penalised us through our salaries for every day we were absent. At the time I felt that if I were to resign I would endanger myself and be branded an 'opponent of the regime'.

"I and other colleagues returned to work with a plan to quit within months to avoid raising any eyebrows. I am resigning soon and will probably leave the country when I do."

Civil servants are not the only ones who are looking for an exit.

In the past week talk of military conscription took a very serious turn after months of rumours and elusive references to it on state television.

All public sector companies in Tripoli were given official notice of the military draft plans through a letter carrying a message that was to be passed on to all male employees.

A civil servant told another friend of mine of the developments in a panic-stricken tone that made us all nervous for various reasons.

"We've been informed that the first conscription phase is for those between the ages of 20 and 40 years old and for those who have completed military training between the years 2000-2011."

As a man, you are required to do this training at some point in your lifetime.

However what you find here is a mixed bag of men who faked medical reasons to get out of military training, men who have not done it at all, men who have false official documents saying they trained when they have not and men who have actually done the training.

News of the conscription has so far prompted some men to make a quick exit from the country to avoid it. Others are making arrangements to leave as soon as possible.

Three months ago, no-one here ever imagined they would find themselves in this precarious situation.

Those civilians opposed to taking part in attacks on their fellow countrymen now face a dilemma.

Either they take the risk of leaving the capital or they stay on and face being forced to fight their fellow countrymen on behalf of a government they silently denounced long ago.

This article was written by BBC Tripoli correspondent Rana Jawad, whose identity was disguised for her safety. You can read her account of reporting undercover from Tripoli here.