Where are today's Steinbecks?

- Published

Millions of men and women have lost their jobs in the latest global downturn - the biggest for decades. Why do we hear so little about them?

Read much about the unemployed, lately? Did you even know there was an employment crisis? You'd be forgiven if you didn't.

Journalists report the numbers, but what about the individual lives the figures represent? You would have thought that a few of those stories might entice writers/film-makers/artists. You would be wrong.

About the numbers first. In Britain and America the employment situation is worse than at any time since the Great Depression. Yet the monthly headline figures on employment are the only ones you read about.

Strong Job Creation Eases Fear of a Swoon, said the headline in the Financial Times last Friday when the US announced 225,000 jobs had been created the previous month. The fact that these new jobs did not prevent the unemployment rate ticking back up to 9% was left unexplained.

Here are some more grim figures from the US Bureau of Labor Statistics:

- The number of people of working age (16-64) in America actively employed is at a 25-year low, around 64%

- One in five men of working age are jobless

- A tremendous number of working people are not in full-time employment - the average working week length is 34.3 hours

And this does not begin to take in people like me.

Harsh world

I was laid off more than five years ago. Today I work full-time as a freelance - but earn 70% less than I did when I had a staff job.

It is a grave disappointment to Her Majesty's Revenue Collectors and a catastrophe for my family.

There are millions like me: people over 50, professional credentials (and achievements), working as "consultants" and not earning a penny, living on savings, trying to re-train. Where in the unemployment figures do we turn up?

I ask the question because I know the answer. When you include us, the actual number of unemployed in America is closer to 20% than 9%.

Now, that number is eye-popping. So why do writers and artists seem uninterested in the human toll of this terrifying downturn?

The question hit me a couple of weeks ago when by chance I saw director John Ford's classic, The Grapes of Wrath, on a long-haul flight. Where was the equivalent for our time?

When I was a kid, The New York Times' thumbnail review of the film called The Grapes of Wrath "American movie-making at its finest."

And it really is. All of Ford's genius for setting up a frame and allowing complex scenes to play out within it is there.

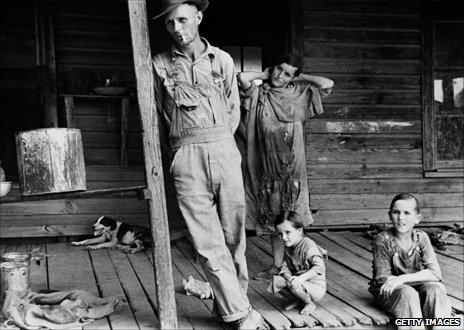

The grinding poverty of the no-luck Joad family is not sugar-coated. Their world looks harsh, the actors' faces look like road maps to hard times.

Up in the Air

The Grapes of Wrath is all the more amazing because it was a product of the Hollywood studio system. Neither Ford nor producer Darryl Zanuck were known as left-wingers. They were quite the opposite.

Yet something about what was happening in their country affected them and they decided to make a film out of John Steinbeck's novel of the same name (now, Steinbeck really was a leftie).

There is a pitiless authenticity to the movie. Ford seems to know these people inside out. Perhaps the distance between those who had everything, like Ford, and the dispossessed, like the Joads, wasn't as great as it is today.

Perhaps it's because the American Midwest was only a generation past wildness and the older actors in the film were for the most part born into that world.

The closest anyone has come in this downturn to dealing with the crisis of losing one's job is the film Up in the Air, a romance about a consultant (George Clooney) brought in to do the dirty work of laying people off.

The film invites more sympathy for Clooney, when his married girlfriend dumps him, than for the folks he has fired.

He tells them that losing your job is a golden opportunity. They will find another job because in America you can always find another job, right? That's what makes America great.

But George Clooney has lost the love of his life - and you only get one of those. The Grapes of Wrath it is not.

I can hear my screenwriter and novelist friends saying it is too soon for work reflecting the human cost of the downturn - the Lehman Brothers collapse was only three years ago.

"We writers need time to let these events percolate through our sub-conscious before we turn them into art," they might argue.

I'm not sure about that. Three years into the Great Depression Steinbeck had already written Of Mice and Men, a tale of migrant farm workers, and had started on The Grapes of Wrath.

At the same time, Henry R Luce, founding editor of Time and Fortune, a right-wing Republican, sent writer James Agee and photographer Walker Evans to the rural American South, to report on the Great Depression's devastating effects.

Their report was so grim that Fortune declined to publish it. The pair published it as a book instead, the classic Let Us Now Praise Famous Men.

I'm not certain that today's editors at Fortune have sent top talent out into the field to document the slow-motion collapse of middle-class life in America.

Screwball comedy

I suppose one reason for the lack of new work reflecting the economic crisis is that the most calamitous aspects of job loss are being avoided this time.

A bit of the social safety net put in place during the Great Depression still exists. Also, in America at least, many households now have two incomes. If one job goes there is still some money coming in.

But I think the primary reason is that Hollywood and the publishing industry have learned just one historical lesson from the Depression: people want entertainment in tough times.

The Grapes of Wrath, the films of King Vidor, even socially conscious gangster films from Warner Brothers were only a fraction of Hollywood's output then. The Depression was also the era of Fred and Ginger, Nick and Nora, screwball comedy and Busby Berkeley.

That hasn't changed. Writers, film-makers, game designers all want to eat - and that's the market they have to create for.

A line of poetry by T S Eliot composed at the same time Steinbeck was writing Grapes of Wrath, and Agee and Walker were having their report spiked, says it best. "Humankind / cannot bear too much reality."

But humankind has to live in the real world with other human beings. And if writers and artists won't put a human face on the jobless numbers, who will?

Michael Goldfarb is a former London bureau chief for National Public Radio, and the author of Emancipation: How Liberating Europe's Jews from the Ghetto Led to Revolution and Renaissance.