Georgia's 'secret' arsenic village

- Published

Arsenic mines and factories in Georgia abandoned after the fall of the Soviet Union are leaking toxic chemicals, and scientific studies show high rates of illness in local children.

But it seems villagers in Uravi, high in the Caucasus mountains in north-west Georgia, are being kept in the dark, and locals know nothing about the harm the pollution could be doing to their young.

The government is aware of the problem, but with its economy still only 60% of what it was in Soviet times, the country just does not have the necessary resources, says environment minister Giorgi Khachidze says.

"All over the country we have the legacy of pesticides, landmines, abandoned factories, sources of radiation. Every day we get information about something and we just don't have the money to sort out all these in a day."

Uravi is a beautiful spot, where hills dotted with small wooden houses rise up from the river to peaks covered in snow. But locals call this the Black Valley.

Zaza Bochirishvili, who runs a local NGO campaigning on green issues, says the whole area is polluted.

"All mountain rivers should have fish but this river does not.

"The arsenic dump, situated at the top of the village, is not completely closed and the rain water goes into the dump, and the water which leaks out of that dump is dangerous."

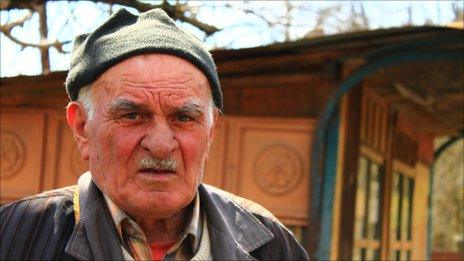

Villager Georgi Gobeshishvili, 81, who worked in the arsenic industry for more than 25 years, is worried about contamination. He says just 0.002gm would be enough to kill a person.

"Just if you touch it with one hand and then eat with the same hand, that's it. That kills."

Recent tests show arsenic levels in the soil around the village are 20-30 times higher than normal. Other scientific studies, from Tbilisi State Medical University, have found arsenic in the blood of local children.

Researchers have concluded that young people in the valley are more likely to suffer from some illnesses, such as acute chest infections, than children elsewhere in the country.

But local people are unaware of this research.

Watch: Angus Crawford visits the site of the arsenic dump

The director of one of the valley's schools, Tamaz Beshidze, says he knows "nothing, absolutely nothing" about the results of any studies.

Teacher Leila Vasadze is also in the dark, but adds the school had to close completely earlier in the year. "The flu epidemic was really strong here this winter, the whole class was off for three to four days, so my class just stopped."

Village nurse Guliko Morosidze shows us the medical records of the children she treats. She says they have the normal coughs and colds, nothing out of the ordinary.

Parents confirm this, and say scientists did come and take blood samples, but told them everything was OK. They say they trust the authorities.

Risk in later life

In the capital, Tbilisi, the researchers behind the studies say they have not told the villagers of their findings for fear of scaring them.

Dr Archil Chirakadze, head of the scientific research centre at Saint Andrew the First-Called University of the Patriarchy of Georgia, says the valley must be decontaminated. But the state cannot afford to, so telling parents is of little use.

"If you give information and the people have no possibility to fight this contamination, what can they do?"

Another academic admits that serious health problems won't be seen until the long-term - later in life, Uravi's young people will be at greater risk of cancer and even leukaemia.

In its own way, the story of the Black Valley is an example of the complex nature of modern Georgia.

The legacy of Soviet rule is a mountain of waste, and an industrial base too small to be able to help pay for the clean-up. That, and a lack of transparency.

For now, it seems, the people of the valley must continue to live with Communism's toxic legacy.

- Published31 January 2012

- Published31 January 2012