The open internet and its enemies

- Published

The Android operating system is billed as open, but Google can restrict access to its Market app store

This essay was broadcast by BBC Click on the World Service as part of a debate on openness. The full programme is available here.

We live in the age of electronics, where many aspects of daily life are shaped - for good or ill - by the capabilities of machines that rely on the flow and detection of tiny electric currents and the opening and closing of silicon-based switches.

These days most of the switches and circuits are in computers, though we should not forget that radio, the medium that many of you will be using to listen to me now, was the first mass-market electronic technology.

The things these technologies can do are truly astonishing, and their application has transformed the lives of us all - not just those like me who have easy access to the latest shiny toys, but even those who live in poverty and may never themselves hold a mobile phone or computer or share information over the Internet.

But no technology exists in a vacuum, and the growing use of powerful digital computers connected by an ever-faster and ever more pervasive networks requires us to ask hard questions about the ways they will be used to shape society.

The idea of 'openness' lies at the centre of this debate.

Defining open

I believe that if we want an open society based around principles of equality of opportunity, social justice and free expression, we need to build it on technologies which are themselves 'open', and that this is the only way to encourage a diverse online culture that allows all voices to be heard.

But even if you agree with me, deciding what we mean by 'open' is far from straightforward:

Does it mean an internet built around the end-to-end principle, where any connected computer can exchange data with any other computer and the network itself is unaware of the 'meaning' of the bits exchanged?

Open source software such as Audacity allows users to contribute to improving code

Does it mean computers that will run any program written for them, rather than requiring them to be vetted and approved by gateway companies?

Does it mean free software that can be used, changed and redistributed by anyone without payment or permission?

Those things count as 'open' to me, but you might have a very different view.

You might not even think that it is a good thing: openness brings its own risks, as we've seen throughout this series of programmes.

Changing reality

Digital information is very hard to control in an open world, because it arrives in a form that allows it to be manipulated by its recipient.

When you listen to the radio or record a TV programme on tape all you can easily do with the result is listen or watch again. You may be able to select which bits you watch, but transforming the stored form is complex and often impossible.

If you are listening to the podcast of this programme, however, then you have a digital file on your computer that you could load into an editing programme like the freely available Audacity, and then you can sloooow me down… cut my words up [up cut words my] or even add [another person's voice] - seamlessly.

Apple's closed App store allows a degree of quality control with the company vetting app software

Those whose businesses rely on limiting people's ability to copy and modify songs or images or video - the 'content industries' - find it hard to cope with the openness I've described, but so do those who want to manage the free flow of information for reasons that are not simply commercial, such as the doctors who keep my medical records or the companies storing my personal e-mails.

In some respects today's Internet is a vast, unregulated, worldwide experiment in openness, and it is already having significant consequences.

It is one that started because of the largely unanticipated consequences of the global adoption of a set of technologies that were built around an assumption of openness without any real concern for the broader impact.

We cannot simply pull down the walls to the unimpeded flow of information and expect no consequences, so while I continue to think that the real benefits of the network will only be seen if we make it as open as possible, I know that openness carries a price.

And of course we could decide to do things differently.

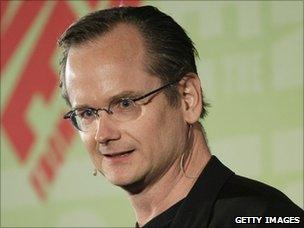

Lawrence Lessig postulated that the architecture of cyberspace defines its rules

Over a decade ago Lawrence Lessig pointed out, in 'Code and other Laws of Cyberspace' that CODE IS LAW.

That means we can change the rules of the internet as easily as we change the code.

Just because we currently have a mostly open network is no reason to believe that there is a pre-ordained path towards constant improvement as we deploy advanced digital technologies throughout the world.

Different choices could be made at every stage, and the outcome is far from determined.

It could be a regulated, managed and limited network of the sort being constructed in China and Libya.

Access to dissenting or distinct voices could be limited and managed.

We could choose the apparent safety of a closed network and a closed society.

- Published21 February 2011