Saving Egypt's precious fire-bombed books

- Published

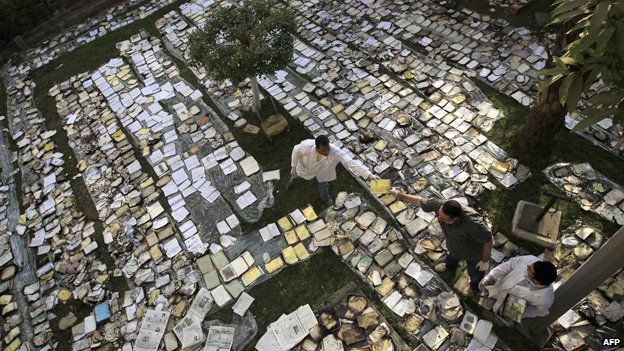

Restorers laid burnt and damaged books out to dry in the Institute's garden

Thousands of historical documents could be lost following a fire at the Institute of Egypt - which began during clashes in Tahrir Square last month - but an army of restoration workers is working day and night to save the country's written history.

The plain-clothes security guard in the dingy ground-floor office at Egypt's National Archives eyes my camera suspiciously.

On the desk in front of him lies a heavy black revolver. After a brief dispute with my guide and phone calls to his seniors, he reluctantly lets me in.

I am led into an adjoining room where, knee-deep in stacks of newspapers, men and women wearing face masks, rubber gloves and white lab coats are hard at work.

It looks like a cross between a hospital operating theatre and a newspaper printing plant. The smell of singed paper hangs in the air.

From this small room, a vast rescue operation is being mounted to save the ancient books and manuscripts, which were damaged after the country's oldest research institute - the Institut d'Egypte - was firebombed during clashes between demonstrators and the army in central Cairo in December.

Founded by Napoleon Bonaparte in 1798, during the French expedition to Egypt, the institute is one of the oldest academies of arts and sciences outside Europe.

Indeed it was Napoleon who led the efforts to compile the institute's most prominent work, La Description de l'Egypte, a 23-volume tome dating back to 1809. Describing Egyptian civilisation, nature and contemporary life it was compiled by more than 150 French scholars.

A first edition of the work has been partly damaged in the fire.

The institute held more than 200,000 rare reference books and bound manuscripts dating back to the 1500s, in five languages: Arabic, French, English, German and Russian.

Many are from the 19th Century, the era of the great Victorian explorers of Africa.

Among its collections were handwritten letters, travelogues and tens of thousands of maps, including a 1752 atlas of Upper and Lower Egypt and a German atlas of Egypt and Ethiopia dating back to 1842.

'Tiny bits of history'

Irina Bokova, Unesco's director general, called the fire an "irreversible loss to Egypt and to the world".

The conservation workers at the National Archives wrap copies of books, drenched as the fire was hosed down, in reams of newspaper to soak the moisture from their pages.

Restorers work long hours to try to save books and documents

The packages, like square-shaped bundles of fish and chips, are then sealed in a vacuum pack.

The nearby corridor is lined with heaps of these plastic parcels. Each needs to be opened, checked and repackaged every three days - a painstaking process that will take several weeks, so workers are staying late into the night to finish the job.

Mountains of blackened books and charred paper fill the room.

Everywhere fragments of paper litter the floor - tiny bits of history beyond salvation.

I tiptoe across the room gingerly, all too aware that I am treading on scraps of paper hundreds of years old. It is a sad feeling, like walking over somebody's grave.

In the corner, a worker is layering pages of a large manuscript with sheets of plain paper. The edges of the pages crumble as he lifts them, the fragments settle on the floor where they will gradually disintegrate into dust.

It feels like the un-making of history.

'This is our heritage'

Mona Mohammed Abdo, the head of book restoration at the National Archives, a woman in a blue-green headscarf with twinkling eyes, takes a break from her work to show me around.

"It's a catastrophe," she says. "It's the first time I've worked on anything of this scale. Thirty truckloads of books arrived in the first few days.

"We had nowhere to put them so, at the beginning, to stop them going mouldy, we were forced to resort to natural drying techniques.

"We spread pages across the ground in the garden and on the rooftops of the building to dry. Some of the books were still smouldering when we opened them," she says. "We had to pour water on them to put out the flames."

The Institute held more than 200,000 precious books and documents

Many of the workers helping are not specialists but ordinary Egyptians who have volunteered.

Twenty-four-year-old Bushra, a pharmacist wearing a pale pink headscarf and full-length pastel blue dress, looks up from the papers she is wrapping and smiles at me.

"This is our heritage, our culture. It's really important. I had to come and help. They said it was going to rain soon so we had to move fast to get things out of the archive office's garden."

Just down the road, several weeks on, books still lie beneath the rubble of the institute.

It is right by Tahrir square, where demonstrators opposed to the military council that has ruled Egypt since President Hosni Mubarak's fall, are still camped out making their voices heard.

The continuing protests have hampered rescue efforts and the building itself is said to be in danger of collapsing. The top floor has already caved in.

Many of its books have been lost for ever.

How to listen to From Our Own Correspondent:

BBC Radio 4: A 30-minute programme on Saturdays, 1130.

Second 30-minute programme on Thursdays, 1100 (some weeks only).

Listen online or download the podcast

BBC World Service:

Hear daily 10-minute editions Monday to Friday, repeated through the day, also available to listen online.

Read more or explore the archive, external at the programme website, external.

- Published18 December 2011