Do herbal supplements contain what they say on the label?

The use of herbal products has increased dramatically in recent years, and as a nation, we spent over 117 million pounds on them last year alone.

Although herbal products are often perceived as ‘natural” and therefore safe, many different side effects have been reported owing to active ingredients, side effects caused by contaminants, or interactions with drugs.

So how do we really know what we are taking? We wanted to find out whether herbal supplements actually contain the herbs they list on the label. Is what’s on the bottle, what’s in the bottle?

Dr Chris van Tulleken joined forces with Professor Michael Heinrich and Dr Anthony Booker from the University College London School of Pharmacy to test a range of the herbal products on sale in the UK and reveal the shocking truth about what’s really in them.

Traditional herbal medicines and food supplements

Herbal products are available in various forms on the UK market.

Firstly, they can be sold as ‘traditional herbal medicines’. In the UK the traditional herbal registration (THR) scheme which is overseen by Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) provides a framework whereby manufacturers of good quality herbal products can register these as medicines based on ‘a tradition of use’. This means that a herbal product has been used traditionally for at least 30 years (15 years ‘non-EU’ and 15 years in the EU, or more than 30 years in the EU).

This not only allows the manufacturer to make a restricted medicinal claim on the packaging (e.g. ‘A traditional herbal medicinal product used to relieve the symptoms of slightly low mood and mild anxiety exclusively based on tradition of use only’), but importantly, the THR means the herbal product has been assessed by various scientifically qualified individuals and that the company complies with certain good manufacturing specifications. Overall, this means that while the evidence for efficacy may be limited, the scheme provides an assurance that you are getting not only a good quality product, but also more reliable advice on how to use it.

The regulations surrounding herbal medicinal products have, however, been interpreted in a variety of ways, and consequently there are a large group of products which remain unlicensed and unregulated. These products are classified as ‘food supplements’. By contrast with the THR products, these products cannot make any specific health claims, however people may still buy them expecting certain therapeutic effects. Their quality requirements are generally based on food legislation, which means that these products are not subject to anything like the same level of legal and manufacturing scrutiny as a THR product.

The experiment

We bought over 70 herbal products from various high street stores and internet retailers. Some of the products were THR herbal medicines, some were food supplements.

The team at UCL then analysed their chemistry to see whether each one really contained what the label says. The three popular herbal remedies we tested were:-

- Milk thistle (Silybum marianum), this is a popular herbal remedy is sold for indigestion and upset stomachs.

- Ginkgo (Ginkgo biloba), which is said to improve memory, concentration and other mental faculties.

- Evening primrose (Oenothera), a product which is sold for hormone balance and ‘healthy looking skin and hair’.

Analysis

Herbal extracts and products are notoriously very difficult to analyse as the extract can often be a very complex mixture of compounds. This can vary depending on how and where the plant has been grown, and how it has been processed. So, the team at UCL used two different, but complementary, methods of analysis to verify the identity of these herbal products and extracts.

High-performance thin layer chromatography (HPTLC) is a sophisticated instrumental technique for the analysis of herbal products and is one of the most commonly used methods in the industry. HPTLC analysis creates a chemical fingerprint of the product which the researchers can then compare to an accepted reference standard for the herb. They look for a broad spectrum of ‘marker compounds’ these are the pharmacologically active and/or chemical constituents within a plant that can be used to verify its potency or identity. For complex samples or where additional confirmation is required, researchers often turn to ¹H nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (¹H-NMR) which allows individual samples to be compared in detail against other samples or to the whole group.

The team’s methodology has been developed through their work on the herbal product for Turmeric (Curcuma longa) and Roseroot (Rhodiola rosea), for which they have found similarly alarming results.

Results

The UCL team carried out tests on both food supplements and THRs.

In every THR product tested, the product contained what was claimed on the label.

However, the food supplements showed a wide range of quality.

Of the food supplement products labelled as Ginkgo that were tested, 8 out of 30 (27%) contained little or no ginkgo extract.

36% of the food supplement milk thistle products contained no detectable milk thistle. Although this is quite a small sample size it is still a startling result. Furthermore, in one case of milk thistle, unidentified adulterants suspected to be synthetic compounds were present in place of milk thistle.

However, all of the evening primrose food products we tested did contain what the packet claimed.

Moreover, it seems that even price is no guarantee of quality. For example, we tested one product that was extremely expensive, but which didn’t contain the ingredient listed on the label.

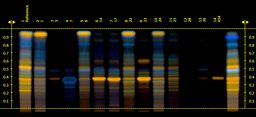

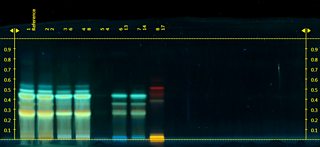

Ginkgo

Milk thistle

These are the HPTLC chemical traces of a sample of the milk thistle products we tested.

The first band on the left here is the chemical ‘signature’ of the herb milk thistle.

- Three of the products had a very similar pattern (numbers 2, 6 & 8) – so these actually did contain milk thistle. One of these as a THR product; the others were sold as food supplements.

- Two others looked similar (13 &14), but the researchers estimate they contained less than 20% milk thistle compared to the reference.

- And two samples (4 & 17) had apparently no milk thistle in them whatsoever.

The research team at UCL believe that the wrong plant material is frequently used to manufacture herbal supplements. The use of cheaper or more readily available ingredients in the manufacture of herbal supplements may be widespread for a number of reasons: suppliers may unknowingly collect the wrong material, or suppliers may knowingly provide manufacturers with cheaper substitutes, or in some cases the manufacturers may be deliberately using cheaper materials to make their product.

Our investigation shows that a regulatory system for herbal products, like the THR scheme, ensures that people have access to safe herbal medicine products. So, if you are considering buying herbal products then do look out for the THR mark– otherwise, you might not just be wasting your money, you might be consuming other, potentially dangerous, ingredients.

We contacted the Food Standards Association and they said this about our investigation:

“The FSA champions the rights of consumers and misleading them in this way is unacceptable. The FSA provides funding for local authorities to take food samples and food supplements are one of the priority areas for testing”.

The results of the our tests have since been passed on to the FSA’s Food Crimes Unit for further investigation.

Useful links

-

![]()

Herbal food supplement labels ‘can be misleading’

From BBC News