Ugandan President Yoweri Museveni signs anti-gay bill

- Published

There was applause as Yoweri Museveni claimed: "Society can do something about it to discourage the trend"

Uganda's leader has signed into law a bill toughening penalties for gay people but without a clause criminalising those who do not report them.

It includes life sentences for gay sex and same-sex marriage, but a proposed sentence of up to 14 years for first-time offenders has been removed.

US President Barack Obama had cautioned the bill would be a backward step.

Mr Museveni had previously agreed to hold it pending US scientific advice.

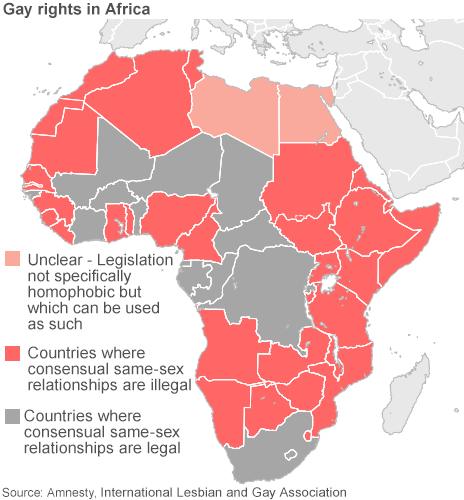

Homosexual acts are already illegal in Uganda.

Correspondents say Uganda's inefficient parliamentary system has meant it has been difficult to get copies of the draft legislation.

The bill signed by Mr Museveni, and seen by the BBC, is significantly different to what was initially reported on Monday - and has been watered down, they say.

The new law allows life imprisonment as the penalty for acts of "aggravated homosexuality" and also criminalises the "promotion" of homosexuality", where activists encourage others to come out.

Earlier drafts of the bill made it a crime not to report gay people - in effect making it impossible to live as openly gay - but this clause has been removed.

Lesbians are covered by the bill for the first time.

Gay activists say they will challenge the new laws in court.

The bill originally proposed the death penalty for some homosexual acts, but that was later removed amid international criticism.

'Very scared'

Government officials clapped after Mr Museveni signed the bill at a news conference at State House.

The BBC's Catherine Byaruhanga, in Uganda, says it is rare for the president to assent to bills so publicly.

But the anti-gay bill has become so controversial that the media were invited to witness its signing, she says.

Gay rights campaigner Claire Byarugaba: "We would rather stay and fight but we know that people in power are way too powerful"

Earlier, government spokesman Ofwono Opondo told Reuters news agency Mr Museveni wanted "to demonstrate Uganda's independence in the face of Western pressure and provocation".

The sponsor of the bill, MP David Bahati, insisted homosexuality was a "behaviour that can be learned and can be unlearned".

"Homosexuality is just bad behaviour that should not be allowed in our society," he told the BBC's Newsday programme.

But a gay rights activist in Uganda told the programme that he was "very scared" about the new bill.

"I didn't even go to work today [Monday]. I'm locked up in the house and I don't know what's going to happen now."

Our correspondent says although Mr Museveni had been apprehensive about signing the bill, he could not convince his party, religious groups and many of his citizens that it was not needed.

His signature is an apparent U-turn from a recent pledge to hold off, pending advice from the US.

In a statement, Mr Museveni had said, external: "I... encourage the US government to help us by working with our scientists to study whether, indeed, there are people who are born homosexual.

"When that is proved, we can review this legislation."

President Obama described it as "more than an affront, and a danger to, Uganda's gay community. It will be a step backwards for all Ugandans."

He warned it could "complicate" Washington's relations with Uganda, which receives a reported $400m (£240m) in annual aid from the US.

- Published18 February 2014

- Published24 January 2014

- Published7 December 2011