On an ancient monument near Republique, fresh graffiti scars the old grey stone - its garish scrawl a slash of anger above the pigeons serenely scratching beneath the arch: “Down with caviar, long live the kebab!” A lone shout in a breadcrumb-trail of slogans, marking the path of protesters through Paris last weekend.

This boulevard of the French capital became, for a few hours that day, an urban battlefield.

Under vast posters showing the latest releases, lines of riot police and armoured vehicles filed past the grand old Rex cinema. In front of them, protesters pulled together barricades from street furniture, as trees were set alight and tear gas filled the air.

“Franck”, who wouldn't give his real name, was among the protesters on Saturday. A construction worker from the Calais region, he says he supports the protests, and came to Paris with four of his friends to join them. They were carrying gas masks and other protective gear.

Franck was prepared for trouble - his friends, he says, were looking for it. By the time they arrived on the boulevard near Republique, they were part of a group of more than 100 people.

“They were overturning cars, breaking shop windows, they set fire to anything they could,” he says. “I’d never seen anything like it. It was anarchy, total chaos. It was war. Everything was on fire - bins, cars, the protective hoarding around the shops.

“The police charged us - the atmosphere was very tense. And the protesters, we all felt like we were in it together.”

French protests have often seemed like a dance between demonstrators and police - direct action has a long and cherished history here. But these weekly confrontations between people and state are different.

Not led by any union or political party, the “yellow vest” protests have unleashed the worst civil disorder Paris has seen for decades.

Four people have been killed, many hundreds injured and billions of euros of damage inflicted on the country’s urban centres.

The French government at one point warned of “serious violence” and “fears for democracy and its institutions”, with at least one protest spokesman calling on people to march on the Elysee Palace, the home of the president. There is a difference between legitimate protest and unacceptable violence, the government has repeated, time after time.

And yet the power of this movement lies, not in the violence at its margins, but in the quiet support of what polls suggest is more than half the country for its basic aims.

Protesters demonstrate on their knees against rising costs of living in Lille

President Emmanuel Macron came to power vowing to face down protesters and drive through long-postponed economic reforms.

For the first 18 months of his presidency, that’s exactly what he did - forcing through changes in the labour law against a backdrop of noisy public protests, and bulldozing past broad, union-led demonstrations on railway reform.

This current crisis erupted - not over a flagship issue - but over a fiscal detail in the budget for next year, a routine rise in eco-taxes on fuel. It wasn’t even a policy that the current government had made. The commitment to annual tax rises on fuel - and especially diesel - in order to fund eco-friendly projects had been part of the previous government’s legacy to Macron.

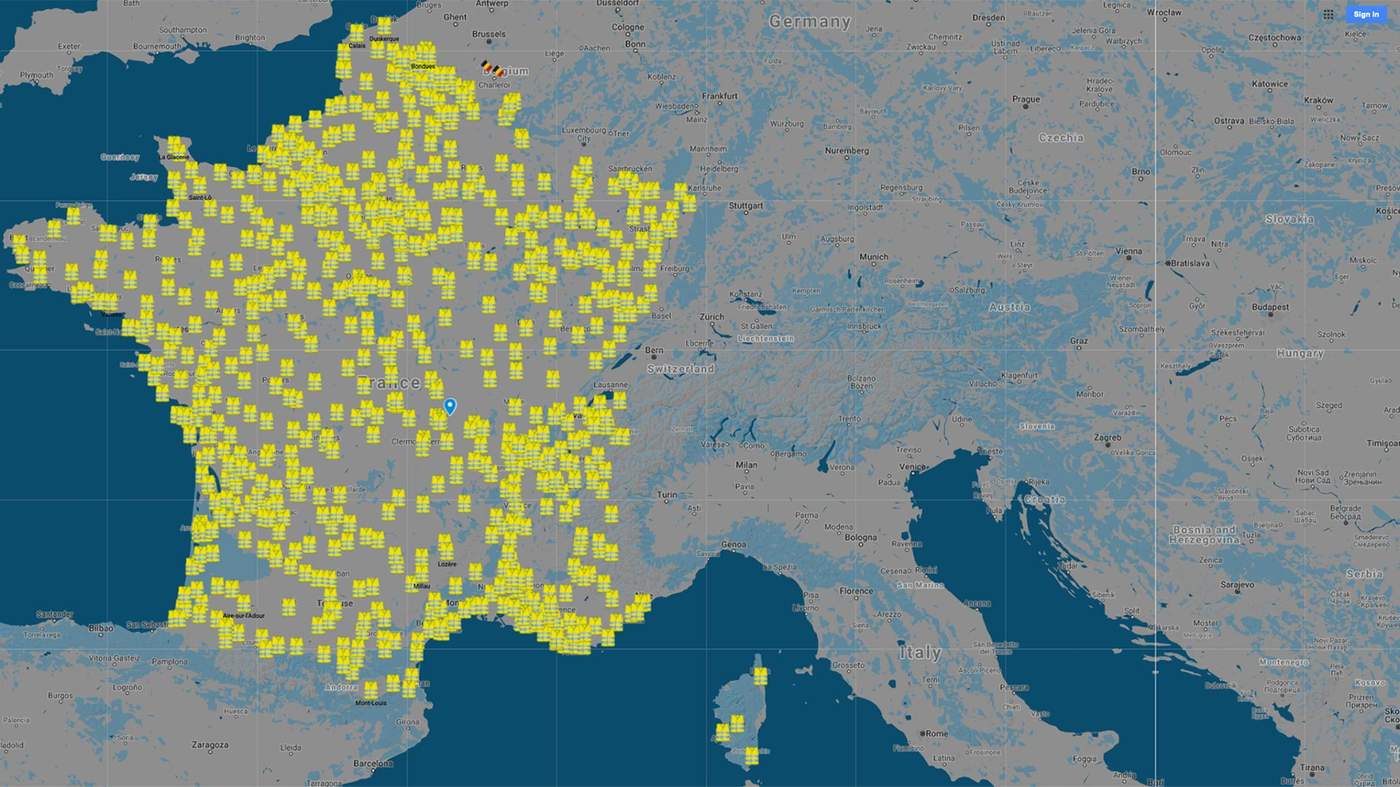

But it was enough to spark a small local rebellion - a handful of motorists who started displaying their regulation hi-vis jackets, or gilets jaunes, in the windscreens of their cars and posting their actions on Facebook.

French President Emmanuel Macron (C) in Paris

Now a movement created on social media, with no recognised leadership, has forced President Macron into concessions that were unthinkable a few weeks ago. How? Because this is not a confrontation about fuel taxes, or any one issue.

It’s about power.

It’s no accident that cars were the spark that ignited this anger. Not needing one has become a status symbol in France.

Those in city centres have a wealth of public transport to choose from, but you need to be rich enough to live in the centre of Paris or Marseille or Bordeaux, and most people are not.

“Economic growth happens in big globalised cities, but the working classes no longer live there,” says Christophe Guilluy, an independent researcher specialising in human geography. “That’s a major change. For the first time in history, they don’t live where wealth and jobs are created. They live in a ‘peripheral France’, characterised by weak economic growth, high unemployment and high anxiety.”

“This economic model creates enormous wealth,” he continues. “But it creates it in a concentrated and unequal way. Since the 1980s, what we are seeing is a weakening of all categories of the middle class.”

Tower block in la Cite des 4000 in La Courneuve in the Paris suburbs

Outside the ring roads that encircle Paris, and other major French cities, you will find the suburbs and satellite towns where workers like Nouria Benatia live. And the gap between the world she works in, and the one she can afford to live in, is growing.

She commutes into central Paris every day to work as a receptionist in a smart hotel just off the Champs-Elysees. After this month’s violent protests in the capital, she says the hotel has emptied and bookings have nose-dived. But she has little sympathy for business owners here.

“To be honest, I still have the same salary, so what does it change for me if the business is working or not?” she says. “I [still] have to go outside Paris to live, and come in to work every day. If the protests were more peaceful, maybe I’d join them.”

Without a car, those in France who have been priced out of the big cities would struggle to get to work, take their children to school and even to shop for groceries.

Petrol prices here are roughly the same as in Germany or the UK - and French diesel prices generally lie somewhere in between its two neighbours. But there is a more general sense of unfairness - a feeling that the struggling middle class are being asked to shoulder more than their fair share of the burden, while France’s millionaires have seen their top rate of tax slashed. And the pain was felt especially keenly this year, because rises in the global oil price had already made fuel more expensive.

In September this year, the government announced its planned increase in the eco-taxes levied on petrol and, particularly, on diesel. Shortly afterwards, the first motorists began showing off their hi-vis jackets in the windscreens of their cars, and Jacline Mouraud, a hypnotherapist from Brittany, published a video on social media saying that motorists were being “hunted”.

French protester Jacline Mouraud

Months earlier, Priscillia Ludosky, the manager of an online cosmetics company from just outside Paris, had launched a petition on the website Change.org calling for petrol prices to be lowered. After the announcement on tax rises, it really began to take off, quickly gathering a million signatures - but still, she says, there’s been no response from the government.

“We are not understood, we are not heard, our opinions are not sought on the big decisions,” she explains. “I get the impression that when the president speaks to people in the street, he’s completely detached from reality.”

Priscillia Ludosky (C) and Eric Drouet (R)

Then, in October, truck driver Eric Drouet, another initiator of the movement, suggested on Facebook the idea of a national blockage, calling on protesters around the country to block roads in their area on 17 November, obstructing and slowing traffic in order to get the government’s attention.

About 290,000 people took part. The gilets jaunes movement had begun.

“The movement started around a tax rise,” says Christophe Guilluy, “but I think it’s simply a pretext, in the same way that Brexit is not fundamentally a confrontation with Europe, but first and foremost a way for people to say ‘we exist’.

“In France, people are using the gilets jaunes as a way to say ‘we exist’ to the elites, to the political class, to those who have forgotten about them for the past 20 years, for the simple reason that they no longer live in the same place.”

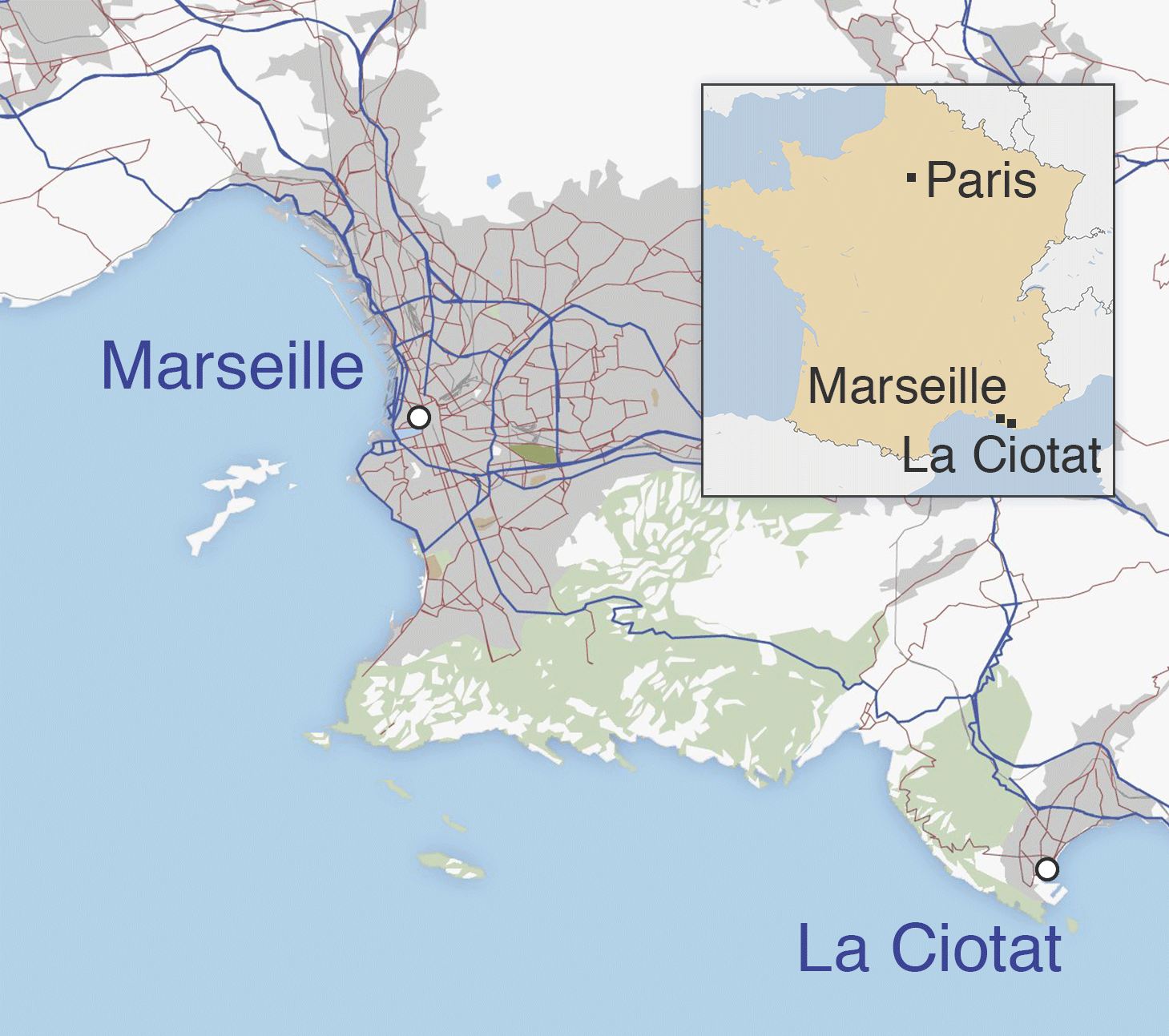

A Christmas tree overlooks the motorway toll station at La Ciotat, 45 minutes’ drive outside Marseille, its tinsel and baubles catching the light from braziers flaring in the drizzle. The protesters here, as on other blockades across France, are settling in for Christmas. Their tents are well stocked with food and drink from local well-wishers, and the noise from supporters honking their horns as they pass along the road frequently drowns out conversation.

More than a dozen people stand around in their hi-vis jackets, well wrapped up in hats and gloves against the cold. Many protest sites, like this one, have developed into semi-permanent camps, snaking along the roadside, with plenty of cover from the elements, and supplies of basic necessities stacked neatly on wooden pallets.

Many are 24-hour operations, and more often than not, there are small rivalries and animated discussions over who should speak for the group.

Antonin Olles is a retired technology teacher. He says social media has played a key role in creating this movement, and restoring to people here a role in the national debate.

“The government wasn’t aware of the power of social media in giving a voice to people who weren’t being heard,” he says, beneath the ear-splitting blares of passing lorries. “Not only does it let people air their grievances, it also lets them communicate with people who feel the same way. These people don’t often get to speak to the TV or the newspapers. It’s a way for them to mobilise; to show they exist.”

Antonin Olles

Some have questioned whether the movement was helped by a change to Facebook’s algorithms. Posts from companies and the media became less prominent, with individual contributions given a boost. But, as with other social media uprisings, the roots of this one run deep.

Guilluy says France is no longer just looking at an economic or a social crisis, but a democratic one: “You have here groups that have not been represented for a very long time by the big political parties. Those who join this movement are those that vote least, the most disengaged from public life. They wanted to have their voice heard, but they haven’t had a way to do it.”

Olles thinks that politicians, union leaders and other representatives have all been discounted.

“People ask themselves - how can this person stand up for me if they don’t know what my life is like? They are relocating everything from villages to big cities - there are fewer local schools, fewer local doctors or hospitals. One woman needed a helicopter ambulance to take her hospital in time to give birth. It’s no wonder people feel like they’re being abandoned.”

The irony, for Emmanuel Macron, is that he came to power promising to rebuild trust in politics, especially among those struggling to thrive in the new, globalised economy. This is the last chance, he told me on the campaign trail last year - if he was to fail, next time it would be Marine Le Pen.

The reforms he promised were designed, he said, to create wealth in order that it could be shared with those who needed it most. It was a policy that aimed to liberalise and protect, but many here feel that the social protection for workers has fallen short compared with the liberal reforms enjoyed by businesses.

(From L) French Prime Minister Edouard Philippe, French President Emmanuel Macron and French Ecology Minister Francois de Rugy meet with representatives of trade unions

President Macron pushed through reforms where previous presidents had feared to tread - reducing the power of the unions in workplace relations, ending the special benefits enjoyed by railway workers, and making it easier for companies to hire and fire staff.

He also ended the wealth tax on all assets apart from property, meaning a 70% cut in the tax for France’s millionaires.

It was meant to boost investment in the economy, but it was seen by many poorer voters as further proof that this former banker-turned-president was still primarily a friend of business, not of the squeezed working and middle class.

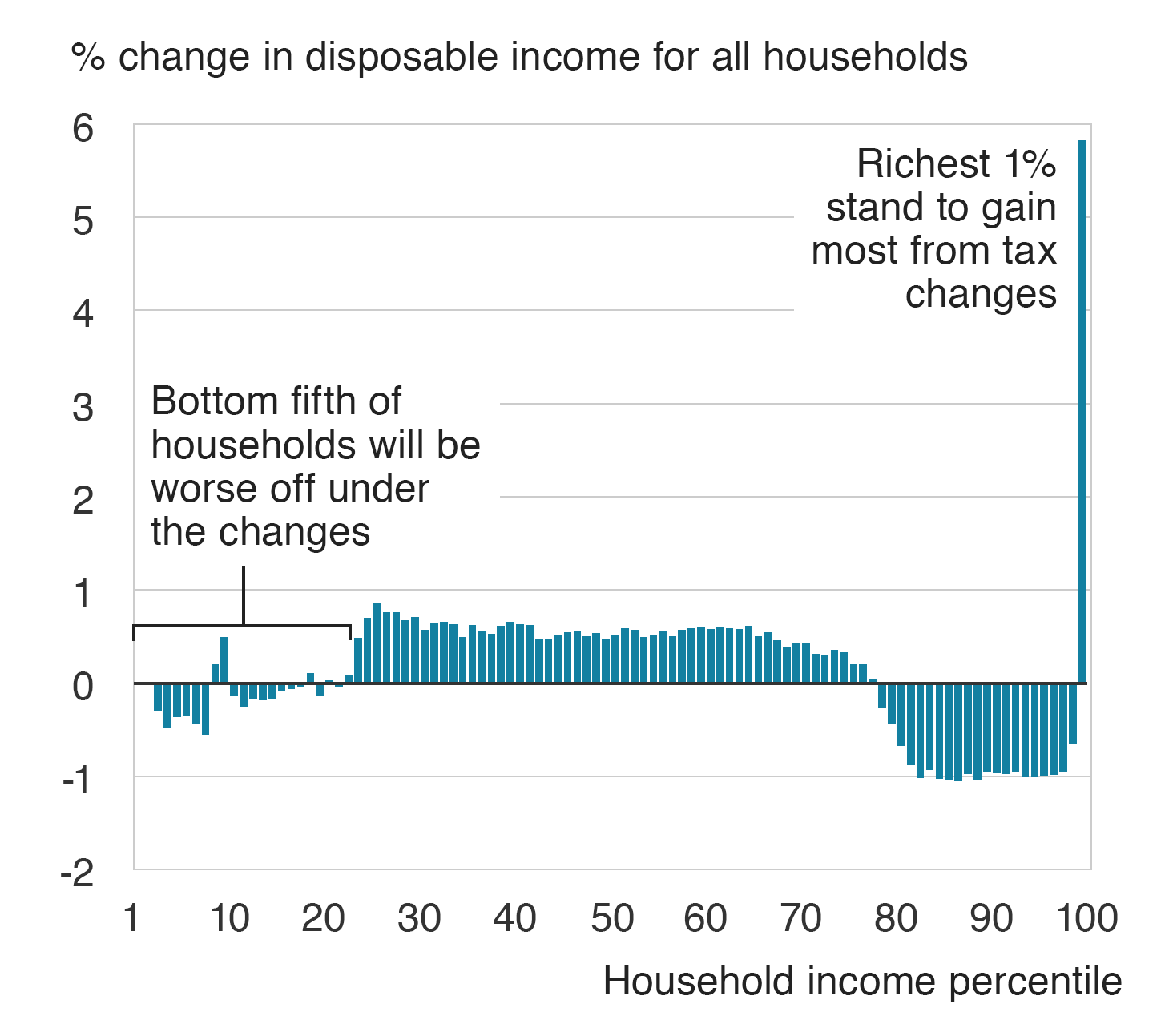

Winners and losers in France's 2018-2019 budget

Source: Institut des Politiques Publiques

France’s Public Policy Institute recently published a review of who had gained and lost under Macron’s presidency so far. It found that the buying power of the poorest in society had slightly shrunk, while those in the economic middle had slightly gained. But the biggest winners were the richest 1%.

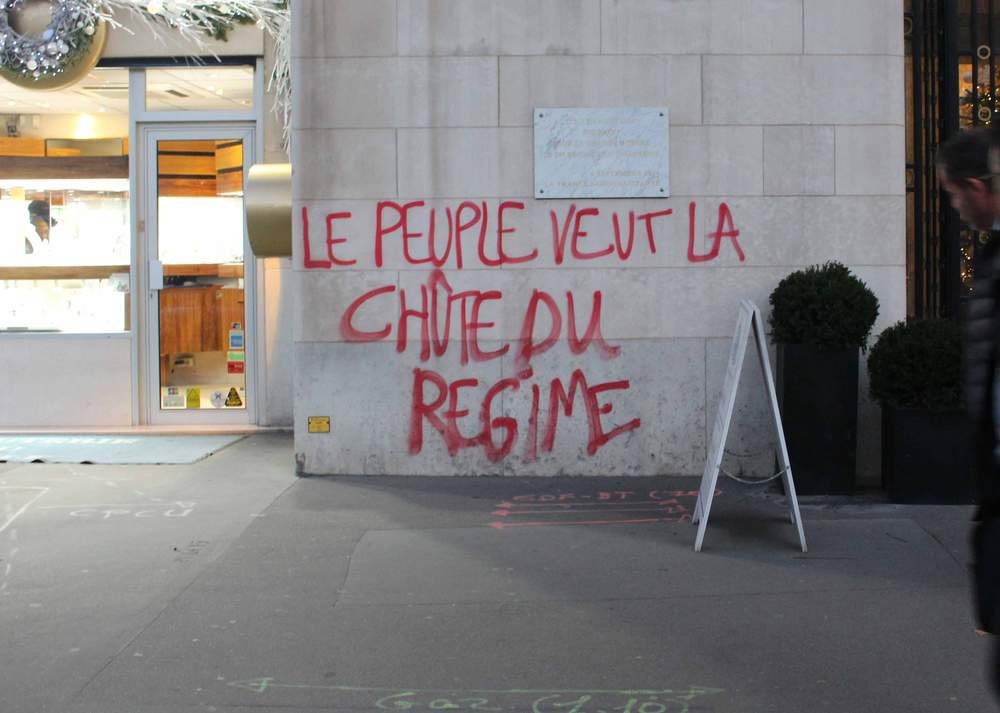

This sense of unfairness emerges time and again in the graffiti that has appeared on walls and monuments in Paris. Much of it calls for the resignation of Macron, or simply the “fall of the regime”. On the Republic’s famous monument at Republique, someone has changed the revolutionary right of “universal suffrage” to read “universal suffering”.

Graffiti reads: "The people want the fall of the regime"

If the roots of protesters’ frustration lie in the big economic shifts of the 1980s, how far did Macron himself encourage it to bloom into open opposition?

“In the last election, many people voted to change their situation and they still find themselves here, so they’ve started to get frustrated,” says protester Antonin Olles. “They’ve realised that those who govern them don’t know what real life is like - for them, poverty is just a set of numbers.”

Despite his warnings against populist nationalism, there have been times when President Macron seemed unaware of the tensions swirling beneath the surface of French society, leading to criticism that he’s aloof and out of touch.

At a public event at the Elysee Palace earlier this year, he told a 25-year-old gardener who complained of not finding work that he would easily find a job if he applied to hotels, restaurants or construction sites. “[If] I crossed the street, I’d find you one,” the president told him. “So go ahead.”

After four weeks of national protest, he addressed the nation in a bid to satisfy demonstrators and drain the movement of momentum. What he offered was the most significant climb-down of his presidency so far - a monthly bonus of 100 euros for those on the minimum wage, an end to tax and social charges on overtime and workers’ annual bonuses, and a freeze in some pension charges.

Protestors take notes as they watch French President Emmanuel Macron's speech on TV on 10 December 2018

There was also an admission that he had sometimes got things wrong. “I know some of the things I’ve said have hurt you,” he said - but there was no formal apology and no change in the government’s economic course. Further reforms planned for next year - on pensions and unemployment insurance - are still set to go ahead.

Instead, the president’s response was to look for solutions at the local level. He announced an unprecedented national debate - on the environment, immigration, decentralisation and political disengagement. He also said he wanted to meet France’s mayors “region by region” to build the basis of a “new contract with the nation”.

La Penne-sur-Huveaune's town hall

The town hall at La Penne-sur-Huveaune, 20 minutes’ drive from La Ciotat, is painted salmon pink. Three huge French flags hang from the poles above the entrance. Dangling from one of them is a hi-vis motorist’s jacket, a gilet jaune.

Christine Capdeville is the Communist mayor of La Penne-sur-Huveaune. When I ask her what she thinks of President Macron’s solution to the crisis, she laughs.

Mayor of La Penne-sur-Huveaune, Christine Capdeville

“President Macron has ignored us from the moment he came to power,” she says. “And now, all of a sudden, he wants us to come to his rescue!

“Can I be honest with you,” she asks. The idea of a national consultation is “absolute rubbish. We’re going to get a piece of paper asking for our grievances, and that’s it. Then everything will carry on just like before.”

The call has gone out for another day of national protest - the fifth consecutive weekend for the gilets jaunes, or “Act 5” as it’s being called. Franck is already planning to come back to Paris with his friends to see more of the action.

The violence he saw last week near Republique will stay with him for the rest of his life, he says. But he liked the atmosphere: “Everyone is together, we are all one, a very good team. It’s not every day you see that.”

That sense of unity among the protesters is what has given the movement its energy, and its power.

Sylvie and Christophe arrived on the Champs-Elysees last Saturday by 09:00. I met them walking up the near-empty boulevard towards the Arc de Triomphe with a group of friends.

“She’s far left,” Christophe told me, “and I’m far-right - and we’re here together for the gilets jaunes!”

“That’s what Macron doesn’t like,” he continued. “That we’re united. He’s brought back solidarity among the French. He’s turned everyone against him. We’re united in combat - at least for now. After that, who knows?”

Student Sylvie

“Our strength is that we’re apolitical,” Sylvie said. “Maybe later when there are new presidential elections, we’ll put together a leaflet, but for the moment we don’t need a leader - that’s our strength.”

Are you scared there might be violence here today, I asked her?

“No,” she replied. “We have nothing left to lose.”

President Macron won last year’s election by cannibalising France’s traditional centre-right and centre-left parties. It deepened splits within the remaining opposition - and has helped keep the political opposition in check ever since.

Now, that divided opposition has been replaced by a social movement that has also united people from left and right, in the same way that Macron did - along with many of those who are disillusioned with traditional politics altogether.

Bruno Bonnell is an MP and founder member of the president’s party, La Republique En Marche. He says the gilets jaunes could emerge as the new opposition to Emmanuel Macron.

MP Bruno Bonnell

“This [movement] looks like ours did originally,” he said in the lobby of the National Assembly. “I remember En Marche when people were saying we had no programme and we didn’t know where we were going. We were debating in bars and cafes, trying to reinvent the world.

“This movement is more about resistance, it’s populist like the Five Star movement or Podemos, but if they gather effectively with leaders and representatives, then we’ll finally face a clearer opposition.”

He says he had visited protest sites many times to ask, specifically, what demonstrators wanted, but that every proposal he made was rejected.

“We are now beyond that. It’s a political conversation, not a conversation about money or compassion.”

Some protesters see a future as a political party. But so far, diversity has been the movement’s appeal - the right of each of its 10,000 members to speak only for themselves. Distrust of representatives is so strong that even the few spokespeople to emerge have come under heavy criticism, even death threats.

But without a leader, or a cohesive agenda, what future does this movement have?

“The leader ought to be the president of France,” Anthony Joubert, one of the founders of the movement, says. “It’s he who has to understand us. He should be spending his time listening, instead of creating a situation where restaurants can charge 15 euros for a bottle of water. As things stand the gilets jaunes are leading ourselves. We are an assembly. We are a national assembly.”

Back at the barricade at La Ciotat, Antonin Olles has gravitated towards the makeshift barbecue as some of the protesters watch a few small piles of sardines crisp on the coals.

There is talk about the next protest - some in La Ciotat say they’re planning to demonstrate here, rather than make the trip up to Paris.

Protesters cook sardines at the tollbooth between La Ciotat and Aubagne

Many have cautioned against dismissing this movement too quickly, even if the level of protest and violence in the capital falls. “The absence of a complete eruption last Saturday doesn’t mean the protest is easing,” cautioned the daily Le Figaro earlier this week. “[The president] won’t win over the country by pulling out his cheque-book or flaunting his intellect, he needs to open his heart.”

“We want a second French revolution,” Olles says. “We want to show the rest of Europe that the people have some power.”

France was seen from the outside as having avoided a populist revolution 18 months ago - but the election of Emmanuel Macron simply papered over France’s problems. Fixing them will take a whole lot more.