Told by David Lemke

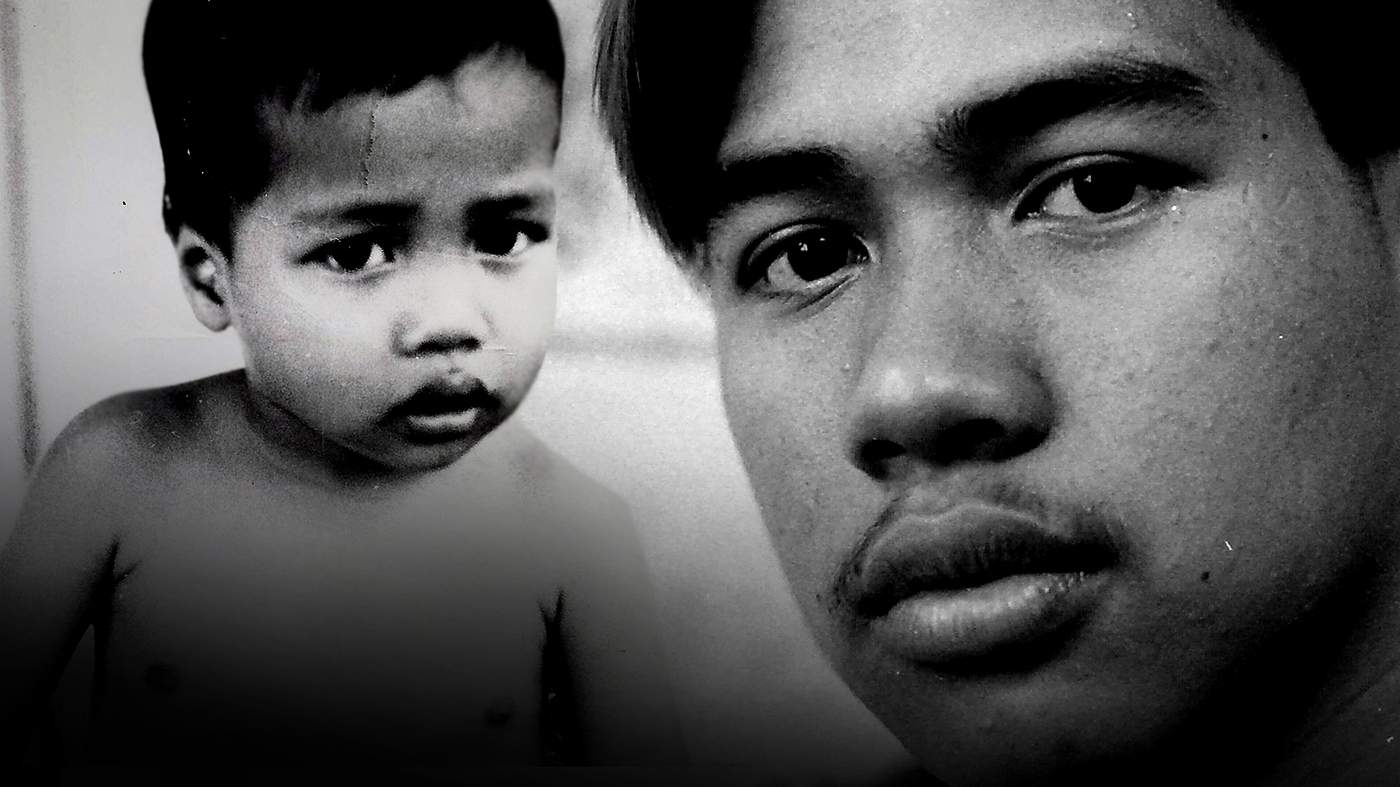

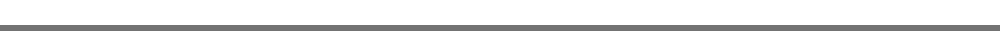

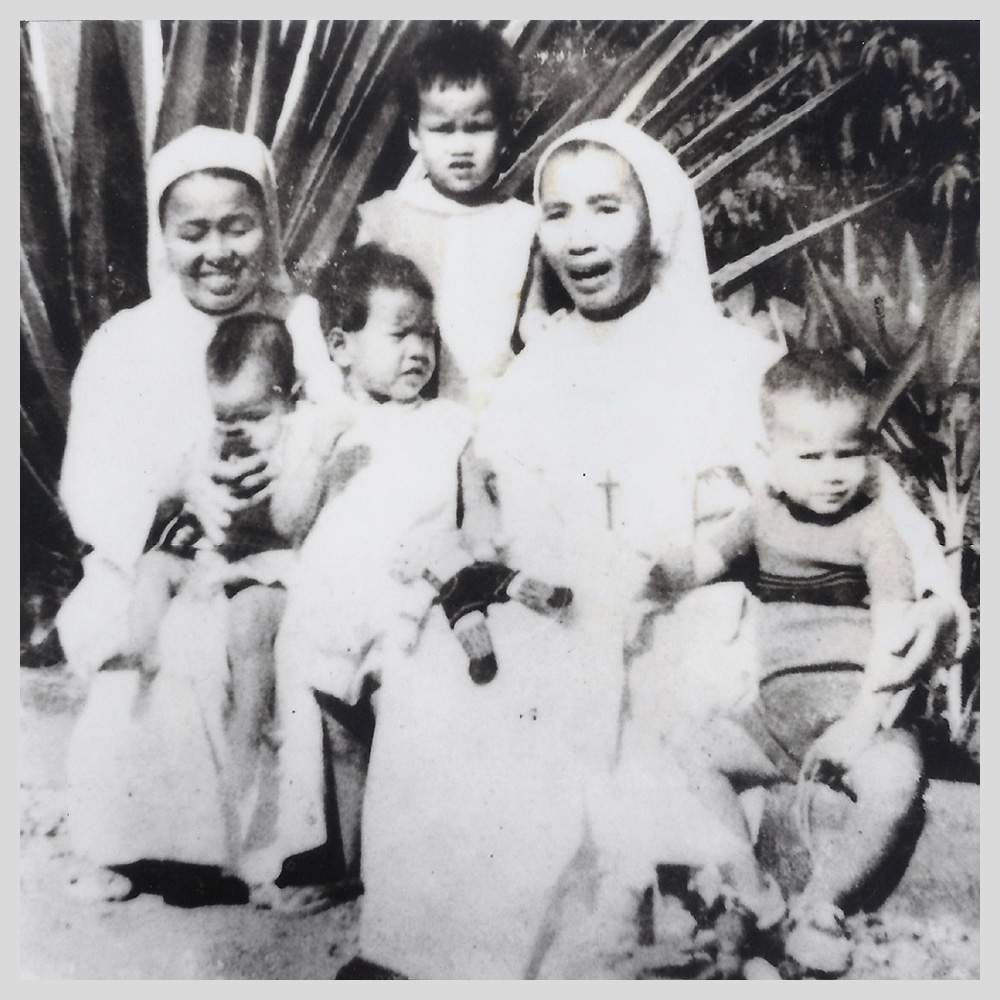

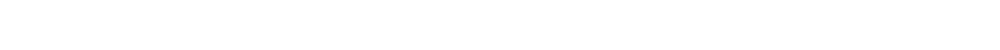

Nguyen Quoc Tuy was born in 1970 or 1971 in Sa Dec, a small town in southern Vietnam’s Mekong Delta.

Tuy - pronounced two-ee - was handed over to the local church, which doubled as an orphanage, when he was just seven days old.

The protracted and bloody Vietnam War - called the American War by the Vietnamese - was still raging in the swampy delta region to the south of Ho Chi Minh City, or Saigon, as it was called then.

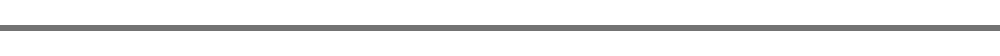

Tuy (r) with the nuns

before he developed polio

When he was one, Tuy contracted the polio virus from contaminated water. The virus attacked the muscles in his legs and left his lower limbs under-developed.

By the time he was three, he was moved to a better-equipped orphanage in Ho Chi Minh City and, because of his health condition, was soon put on an adoption list.

Thousands of miles away, a couple on the west coast of the United States were preparing to give him a new home.

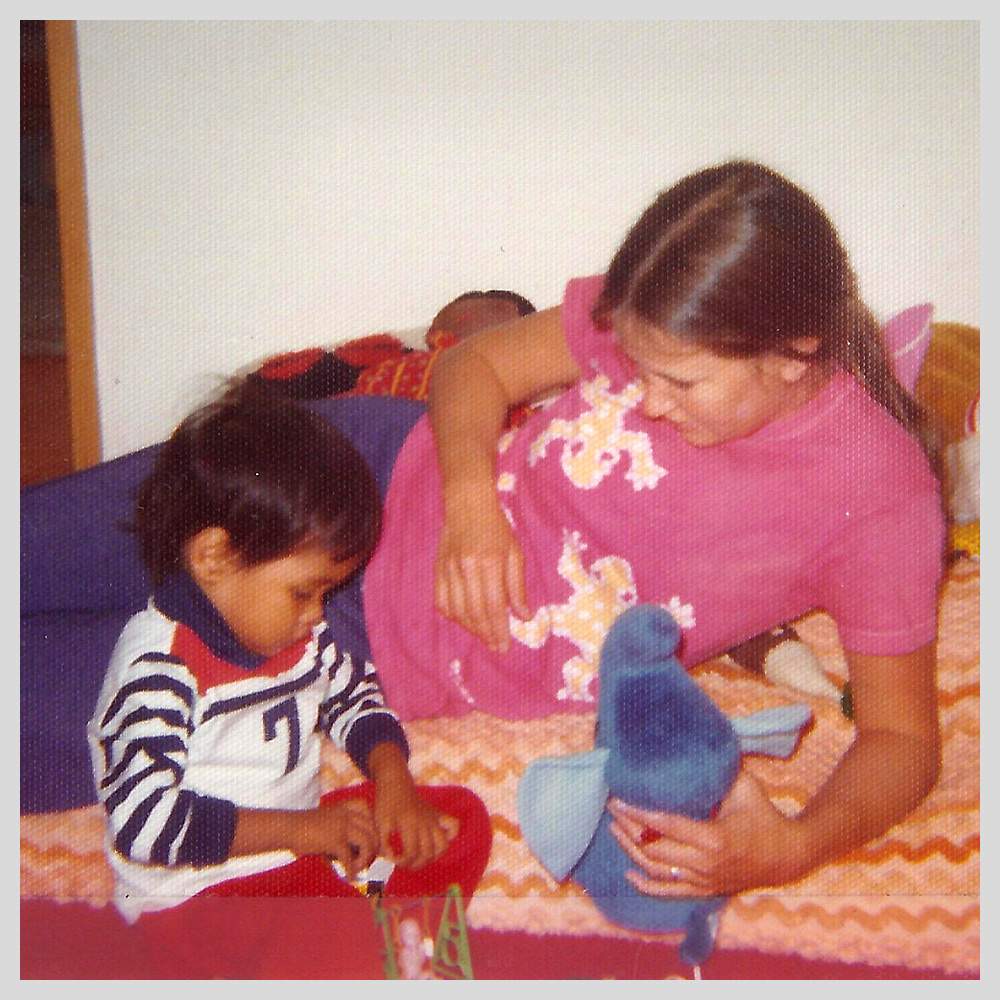

Thomas and Tuy hang a Christmas stocking

‘Diabolically intelligent’

Tuy’s early days in Berkeley, northern California, were not easy.

His anxieties had been well noted by staff at the orphanage, and being in a new environment did little to allay his fears.

Instinctively, Tuy would either save or hide every bit of food he was given.

Kristin with Tuy

“He kept extra food in a bag that a family friend made for him, and he carried that bag wherever he went,” says Kristin.

“He also hid the toys he wanted to keep track of in heater vents, so he could find them later.

“For the first six months, I carried him everywhere to make him feel secure.”

Gradually, Tuy began to open up and trust his new parents and siblings.

He also became more confident as he overcame the daily physical challenges he faced because of the lack of muscles in his legs.

Kristin recalls a visit to a park in the hills above Berkeley, when Tuy was watching his brothers and sisters having fun in a playground.

She observed as he crawled over to the ladder of a slide, climbed up by himself, looked around from the top and then slid down on his own.

“It was at that moment I knew he would be OK, and that challenges for Tuy were just things to overcome.”

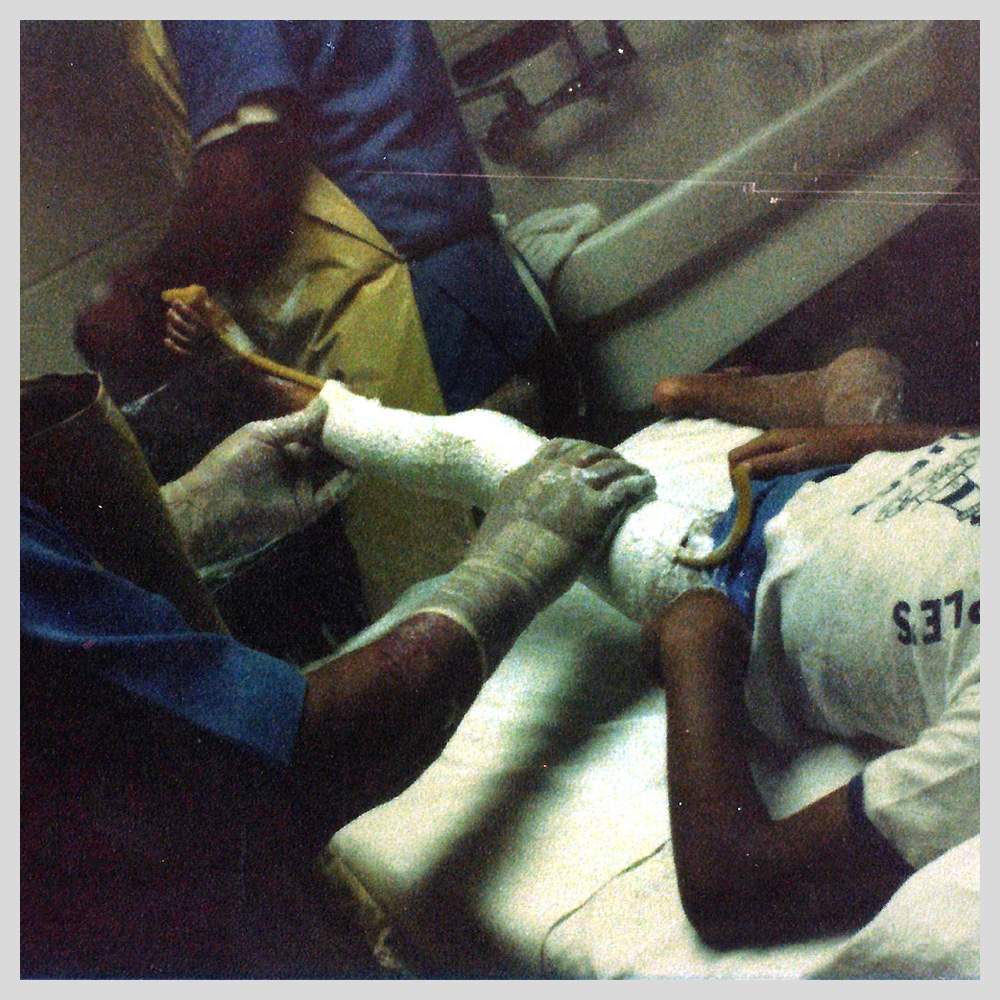

Tuy had to have major corrective surgery because his legs began to grow but the muscles and nerves did not.

Tuy's corrective surgery

He got around on crutches and leg braces, picked up spoken English quickly, and before turning six had learned how to hike, bike, climb and ski using outriggers (forearm crutches with ski tips mounted to the base).

Yet as Tuy entered California’s education system, new obstacles impeded his progress. Teachers assumed he was lazy. “I’d read a sentence in class, and then I’d be done,” says Tuy.

Both Kristin and Thomas were perplexed as to why Tuy fell behind in basic reading.

“One night my mom had a theory,” says Tuy. “She came into my room and handed me one of my reading books upside down. I could read it fine.

“That’s how we went on to discover that I was severely dyslexic.”

With affection, his siblings describe their brother as “diabolically intelligent”.

“When all the other kids went out to play, I had to do something else,” says Tuy.

“I got really good at chess. I started carving and whittling wood. I read almanacs like you wouldn’t believe - just to have conversation material at dinner time.”

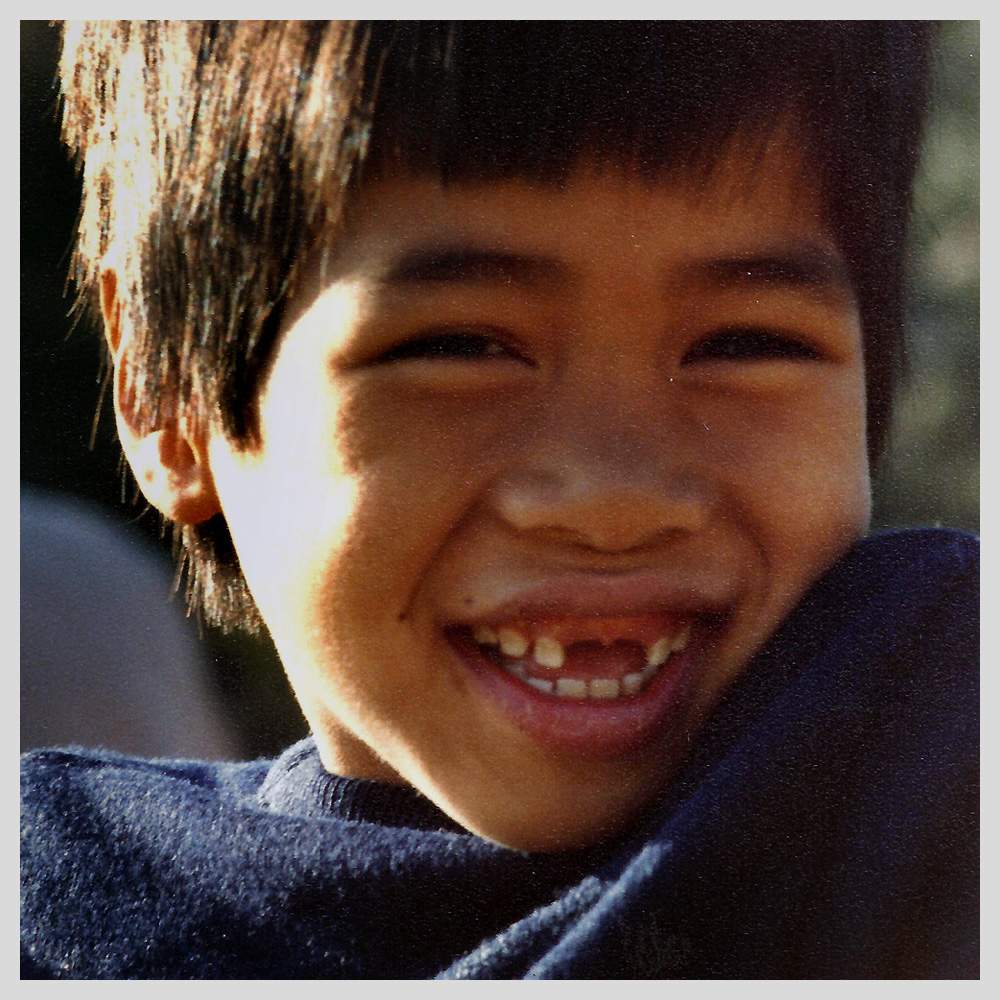

But Tuy’s interest in building things and problem-solving gradually affected his performance in high school.

“He would take wire coat-hangers from home and skip math classes to make bar puzzles - the type you have to physically manipulate to solve,” says Kristin.

“Though this impressed his friends, his grades in the missing classes were less impressive. It became clear that a big public high school didn’t give him the support or opportunities to learn that he was going to need.”

So, after a spell at a local private school in nearby Oakland, Tuy moved out of the family home.

He travelled more than 2,000 miles to Big Island in Hawaii - where he had spent summers with his family - to attend a much smaller private boarding school.

There, Tuy felt more independent - and island life suited him. He identified so strongly with Hawaiian culture that he used to pass himself off as an islander.

He even set up a shop in the school dormitory selling noodles, sweets and fizzy drinks to make some cash on the side.

Good Morning Vietnam!

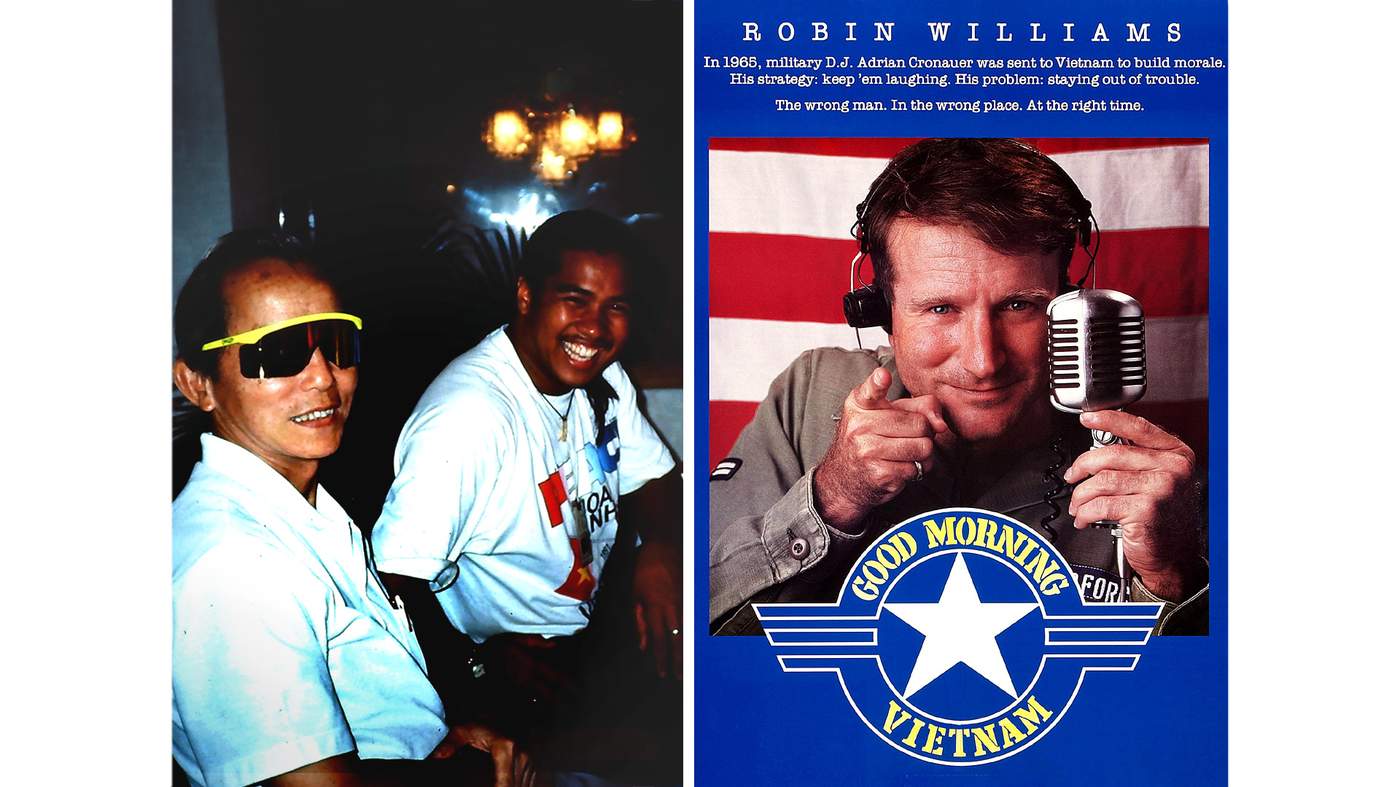

Tuy readily admits he became aimless and easily distracted as a young adult. But in 1991, he got the chance to travel to Vietnam with Kristin.

His parents had always been open about where he had come from and Kristin had taken him on previous trips to Asia, but this was the first time since the war that they - as American civilians - had the opportunity to visit Vietnam.

Kristin was helping to organise the first peace walk in Vietnam to protest against America’s trade embargo.

The trip mixed US war veterans with peace workers and returning overseas Vietnamese.

“In 1991, Vietnam was a totally different place compared to today,” says Tuy.

“It’s hard to describe, but there’s something about returning to your country. Up until then, Vietnam wasn’t really a conscious feeling for me. But as we landed, the experience became overwhelming.

“The Hanoi airport was really small at the time. You walked from the plane to the terminal. I stopped half-way and kissed the ground. It was just something I felt I had to do.”

Planting a peace pole in Ho Chi Minh City

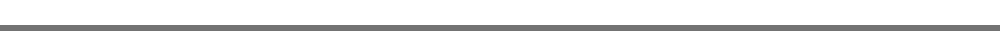

Of all the planned marches, perhaps the strangest one was in front of two curious monkey families on Monkey Island - one of the 1,600 islands in Ha Long Bay, a Unesco heritage site.

Tuy remembers how they all had dinner that evening on the bay’s main island of Cat Ba.

Ha Long Bay, Vietnam

“We were all sitting at our tables, and our Vietnamese hosts, including an army general, invited me to join them to eat.

“We all ended up drinking quite a lot. I had a cassette of the soundtrack to the Robin Williams’ film - Good Morning Vietnam. I convinced them to play that, sitting with this general and getting drunk off cheap Russian alcohol.

“It was bizarre and awesome all at once.”

Tuy and Kristin had hoped to head into the Mekong Delta - Tuy’s birthplace - after the peace walks were over, but travel restrictions against foreigners meant that was impossible.

The visit had a lasting effect on Tuy. He felt that a whole new world had opened up to him.

Unfinished business

Back in the US, Tuy dived head first into as much Vietnamese culture as he could - including getting to know the adopted Vietnamese children of some friends of his parents.

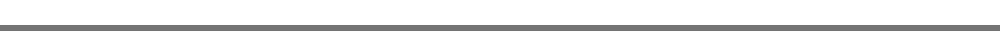

The DeBolt family - also based in northern California - became widely known in the US for raising a large family of adopted children, seven of whom were disabled and from Vietnam.

One of those was among the thousands of babies and children who were airlifted out of Vietnam in the last days of the war.

They went on to be adopted by families in the US, Canada, Australia and Europe.

Tuy fitted right in. He became close friends with Ly, Tich and David.

They spent their time hanging out, playing a Vietnamese card game called Tin Lin, eating Vietnamese food and drinking café sua da (iced coffee with plenty of sweetened milk).

So in 1993, when Ly was flying to Vietnam to get married, Tuy agreed to join his friends for a three-month stay.

This time, he would be able to travel within Vietnam more freely than he had done with the 1991 peace marchers.

He also had unfinished business in the Mekong Delta.

“I just wanted to see the town of Sa Dec and the first orphanage I had been put in,” he says.

“I hoped to simply thank the nuns there and, in a way, seeing the people of that region would be like seeing my mother and father.”

Tuy and his friends stayed at a hotel in Ho Chi Minh City, and the owners - a retired army officer and his wife - offered to help rent a car and drive Tuy, Tich and David into the remote Mekong.

Bad roads and washed-out bridges meant the journey was much more difficult than they’d imagined.

Travelling through Vietnam was not easy, and for a disabled person it was just that much harder. So it was decided that the hotel owners would venture ahead with Tuy’s papers by boat to Sa Dec, to visit the orphanage.

A few hours later, they returned with news.

The nun who had signed Tuy’s paperwork - Sister Desiree - was now living in the nearby city of Can Tho. Finding her proved to be relatively easy.

While she couldn’t offer any information about his parents, she did offer to be his godmother.

David and Tuy meet Sister Desiree (r)

“Sister Desiree was awesome,” says Tuy. “I didn’t think I was going to find anyone - so just finding the nun who’d signed the birth certificate was incredible.”

For the next two and a half months, Tuy stayed with his friends in Da Nang, a coastal city in central Vietnam. He was having a great time, but felt torn.

His desire to see Sa Dec for himself remained strong, and so he decided to make one more attempt to get there before leaving Vietnam, to finally close that chapter of his life.

Three days before his flight back to the US, Tuy left Ho Chi Minh City once again with his friends and the same hotel owners.

This time, after more than five hours of driving on pothole-riddled roads, they made it.

The arrival of this unusual group of disabled Vietnamese-Americans created an immediate buzz. The local market almost stopped trading, as people began to crowd around the front gates of the orphanage.

Tuy remembers saying hello to the children, and sitting on the cracked concrete benches looking at the faded orange paint on the walls.

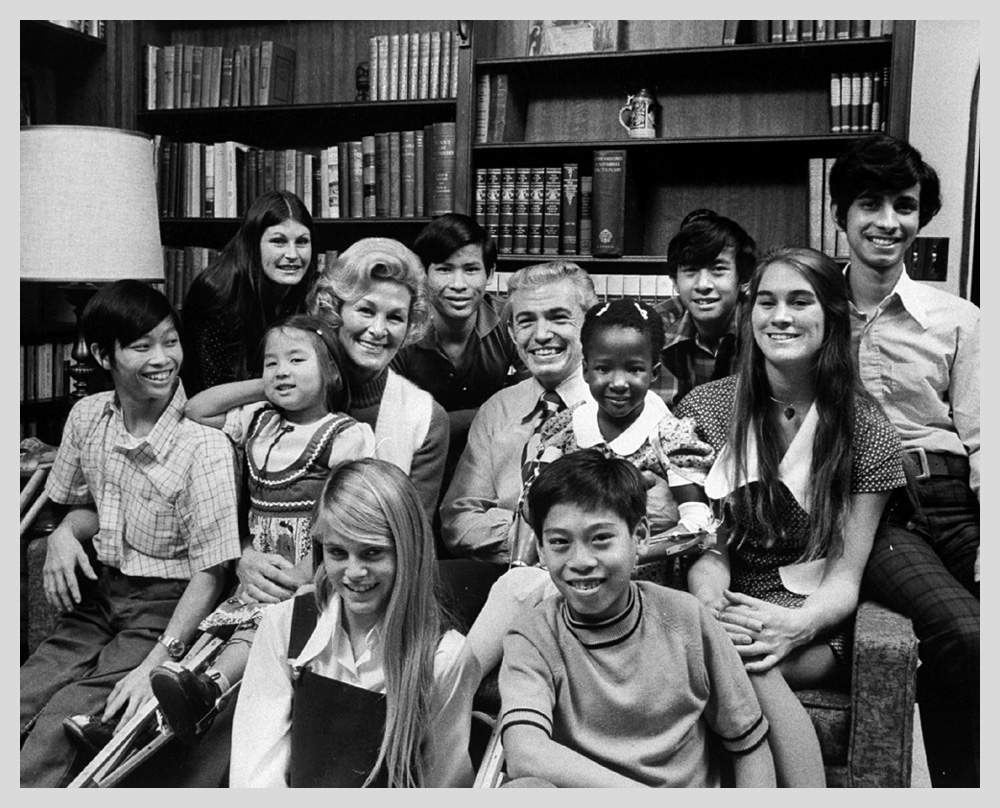

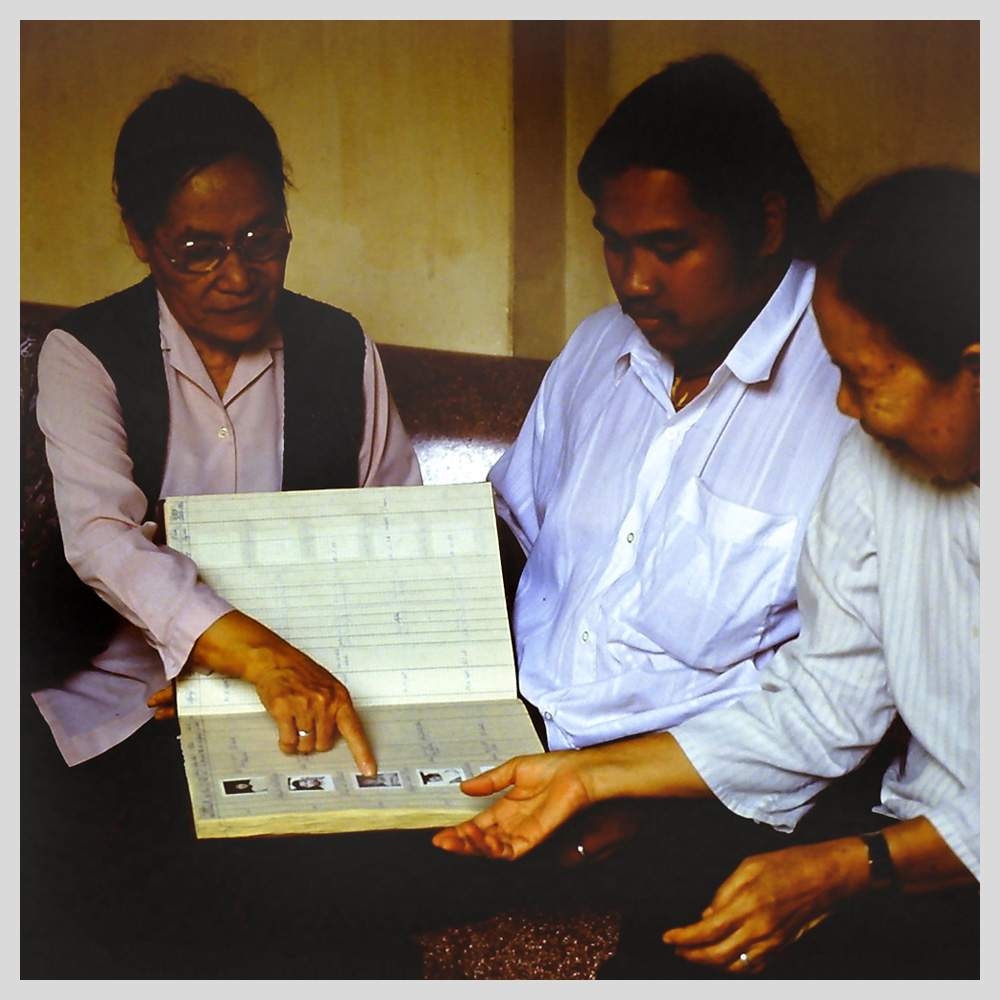

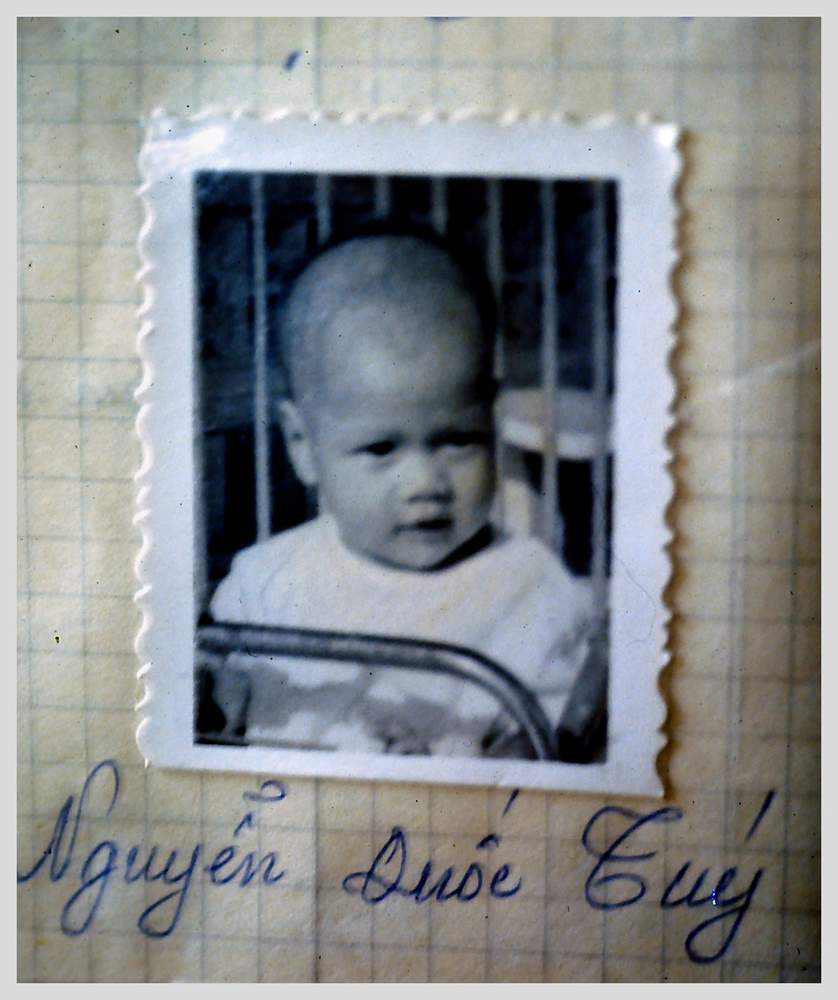

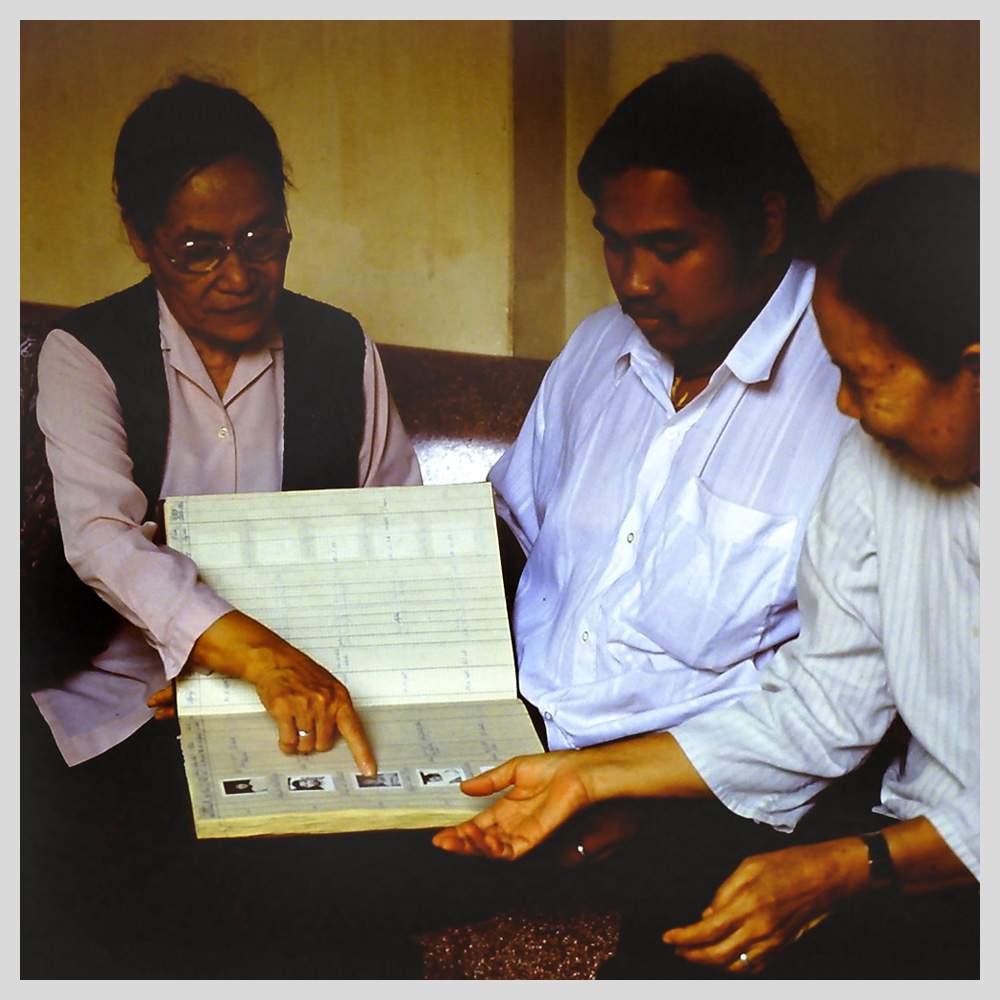

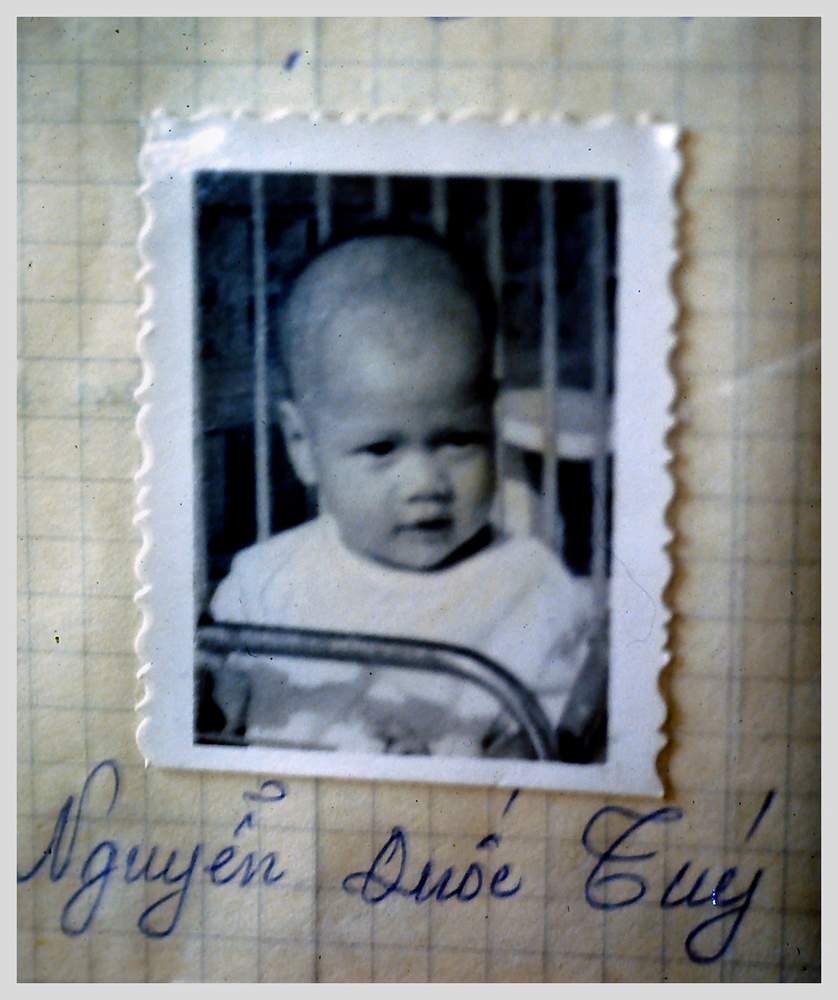

The nuns presented Tuy with a ledger of all the orphans who had stayed with them.

Turning the pages, Tuy arrived at entry 313 and saw his baby photo with the name Nguyen Quoc Tuy - the same as on his birth certificate.

Written underneath was: “mother/father - unknown”.

Tuy's entry in the ledger

“I thought that was astonishing, that they still had these records and my name in Vietnamese was indeed the correct one,” says Tuy.

Outside, the excitement on the street was growing.

“Some in the crowd outside had started to come into the church courtyard to get a look. My story was spreading like wildfire through Sa Dec.”

At one point, a woman came into the church - the nuns clearly knew her. She was introduced to Tuy as Phien, and was shown the baby photo in the ledger.

Tuy was told that in the orphanage, older children were put in charge of the younger ones. Phien, it turned out, had cared for him when she was seven years old.

It was pure coincidence that she was in town that day. She’d been heading to hospital to see a sick relative, but had stopped at the orphanage to visit the nuns.

Phien began to speak quite animatedly to the nuns - but Tuy didn't speak Vietnamese and had no idea what was being said.

David, Tuy’s Vietnamese friend from the DeBolt family, began to interpret.

And what he began to reveal, Tuy says, made “my head feel like it was boiling”.

Phien, it turned out, had information about Tuy’s mother.

She was still alive.

I just wanted to see the town of Sa Dec and the first orphanage I had been put in,” he says.

“I hoped to simply thank the nuns there and, in a way, seeing the people of that region would be like seeing my mother and father.”

Tuy and his friends stayed at a hotel in Ho Chi Minh City, and the owners - a retired army officer and his wife - offered to help rent a car and drive Tuy, Tich and David into the remote Mekong.

Bad roads and washed-out bridges meant the journey was much more difficult than they’d imagined.

Travelling through Vietnam was not easy, and for a disabled person it was just that much harder. So it was decided that the hotel owners would venture ahead with Tuy’s papers by boat to Sa Dec, to visit the orphanage.

A few hours later, they returned with news.

The nun who had signed Tuy’s paperwork - Sister Desiree - was now living in the nearby city of Can Tho. Finding her proved to be relatively easy.

While she couldn’t offer any information about his parents, she did offer to be his godmother.

David and Tuy meet Sister Desiree (r)

“Sister Desiree was awesome,” says Tuy. “I didn’t think I was going to find anyone - so just finding the nun who’d signed the birth certificate was incredible.”

For the next two and a half months, Tuy stayed with his friends in Da Nang, a coastal city in central Vietnam. He was having a great time, but felt torn.

His desire to see Sa Dec for himself remained strong, and so he decided to make one more attempt to get there before leaving Vietnam, to finally close that chapter of his life.

Three days before his flight back to the US, Tuy left Ho Chi Minh City once again with his friends and the same hotel owners.

This time, after more than five hours of driving on pothole-riddled roads, they made it.

The arrival of this unusual group of disabled Vietnamese-Americans created an immediate buzz. The local market almost stopped trading, as people began to crowd around the front gates of the orphanage.

Tuy remembers saying hello to the children, and sitting on the cracked concrete benches looking at the faded orange paint on the walls.

The nuns presented Tuy with a ledger of all the orphans who had stayed with them.

Turning the pages, Tuy arrived at entry 313 and saw his baby photo with the name Nguyen Quoc Tuy - the same as on his birth certificate.

Written underneath was: “mother/father - unknown”.

Tuy's entry in the ledger

“I thought that was astonishing, that they still had these records and my name in Vietnamese was indeed the correct one,” says Tuy.

Outside, the excitement on the street was growing.

“Some in the crowd outside had started to come into the church courtyard to get a look. My story was spreading like wildfire through Sa Dec.”

At one point, a woman came into the church - the nuns clearly knew her. She was introduced to Tuy as Phien, and was shown the baby photo in the ledger.

Tuy was told that in the orphanage, older children were put in charge of the younger ones. Phien, it turned out, had cared for him when she was seven years old.

It was pure coincidence that she was in town that day. She’d been heading to hospital to see a sick relative, but had stopped at the orphanage to visit the nuns.

Phien began to speak quite animatedly to the nuns - but Tuy didn't speak Vietnamese and had no idea what was being said.

David, Tuy’s Vietnamese friend from the DeBolt family, began to interpret.

And what he began to reveal, Tuy says, made “my head feel like it was boiling”.

Phien, it turned out, had information about Tuy’s mother.

She was still alive.

“She lives quite far away and it may take a while, but she can go and bring her back here to meet you,” David told him.

“I was going numb,” says Tuy. “I had no idea how long I had to wait. I was happy, scared and sad.

“’Who is she? Why is she? What is she?’ I thought. ‘What will it take to prove to her I am who I am, or vice versa? Is it a scam to take advantage of me? If it is, what do I do? If it isn’t, how will I handle it?’”

As they waited, Tuy watched as his friends ate lunch. Afterwards they gathered on the front steps of the church.

“Time was slow, and yet also a blur,” Tuy says. “I remember just looking back and forth across the sea of faces in the gathered crowd.”

Eventually, a commotion began at the gates. What seemed to be the town’s entire population was parting for a small group of people inching their way forward.

When the group reached the front, a small old lady wearing glasses popped out in front of Tuy.

In a rush, Tuy blurted out the sentence in Vietnamese that his friends had been trying to teach him.

“Con trai của mẹ đã xa nhà 20 năm nhưng bây giờ con ấy đã trở về.”

In English it translates as, “Your son has been gone for 20 years, but now he has returned.”

There was a moment of silence, before the people at the front of the crowd started gesturing to Tuy.

“People began pointing at a second lady who had stepped out from behind the first one,” he says. “The lady I spoke to first wasn’t the right one!”

“It was dead quiet, until someone in the crowd yelled out, ‘So which one is your kid?’” says Tuy’s friend Tich. “People laughed, and that broke the tension.”

The second woman walked over to Tuy and grabbed him by the back of the head, pulling him down to her level. She parted his hair, which at that time was quite long.

“I have this birthmark on my head,” says Tuy. “It’s one of the reasons why I had grown long hair, to hide it.”

When the lady saw the mark, she released him and hit him on the arm proclaiming: “This is my son!”

“Everybody cheered,” says Tuy. “I still had no idea what was happening or what was being said - so David and Tich translated for me.

“It was in that instance, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that this woman proved to me that she was my mom and that I was her son.

“It was something only a mother could possibly know.”

“She lives quite far away and it may take a while, but she can go and bring her back here to meet you,” David told him.

“I was going numb,” says Tuy. “I had no idea how long I had to wait. I was happy, scared and sad.

“’Who is she? Why is she? What is she?’ I thought. ‘What will it take to prove to her I am who I am, or vice versa? Is it a scam to take advantage of me? If it is, what do I do? If it isn’t, how will I handle it?’”

As they waited, Tuy watched as his friends ate lunch. Afterwards they gathered on the front steps of the church.

“Time was slow, and yet also a blur,” Tuy says. “I remember just looking back and forth across the sea of faces in the gathered crowd.”

Eventually, a commotion began at the gates. What seemed to be the town’s entire population was parting for a small group of people inching their way forward.

When the group reached the front, a small old lady wearing glasses popped out in front of Tuy.

In a rush, Tuy blurted out the sentence in Vietnamese that his friends had been trying to teach him.

“Con trai của mẹ đã xa nhà 20 năm nhưng bây giờ con ấy đã trở về.”

In English it translates as, “Your son has been gone for 20 years, but now he has returned.”

There was a moment of silence, before the people at the front of the crowd started gesturing to Tuy.

“People began pointing at a second lady who had stepped out from behind the first one,” he says. “The lady I spoke to first wasn’t the right one!”

“It was dead quiet, until someone in the crowd yelled out, ‘So which one is your kid?’” says Tuy’s friend Tich. “People laughed, and that broke the tension.”

The second woman walked over to Tuy and grabbed him by the back of the head, pulling him down to her level. She parted his hair, which at that time was quite long.

“I have this birthmark on my head,” says Tuy. “It’s one of the reasons why I had grown long hair, to hide it.”

When the lady saw the mark, she released him and hit him on the arm proclaiming: “This is my son!”

“Everybody cheered,” says Tuy. “I still had no idea what was happening or what was being said - so David and Tich translated for me.

“It was in that instance, beyond a shadow of a doubt, that this woman proved to me that she was my mom and that I was her son.

“It was something only a mother could possibly know.”

And my father?

“Through the tears I asked who my father was and if he was here too,” says Tuy.

“She told me he was Filipino.

“That hit me in the face like a slap. When I was in Hawaii all the locals used to tell me I looked Filipino and it felt like they were challenging me.

“I had identified solely as being Vietnamese, but it turns out they were right all along.”

Tuy says he and his birth mother, Nguyen Thi Be, sat for a while and talked - with his friends interpreting.

“I was totally just grooving off her speaking. I had so much to say, but wasn’t able to. I actually felt ashamed and shy - I was culturally inept.

“She told me how when I was born, she was extremely ill and not able to care for me. Fearing for her own life, she arranged for me to be taken to the church.

“When she recovered she tried to get me back, but she said the nuns had told her that the rules were once a child had been given up, it could not be returned.

“When the war was over, my mom lost all hope of ever seeing me again.”

Thi Be gave Tuy a name and a place regarding his father - Fantaleon Sanchez and the city of Calamba in the Philippines.

Six months after the mother-son reunion, Tuy landed in the capital Manila, joining his adopted father Thomas, to look for his birth father.

Thomas, a baritone vocalist, had been booked to perform with the country’s national philharmonic orchestra - it seemed an ideal opportunity to search.

It was 1994, the internet was in its infancy, and they had no idea exactly how to start looking in Calamba - which at the time had a population of about 200,000 people.

The driver who took them the 30 miles or so from Manila suggested stopping at the local municipal offices.

“Right as you enter the building there’s a missing persons bureau,” Thomas recollects.

“Although no-one was technically missing, the officer at the desk - named Benito - took the photo that Tuy had brought of his Vietnamese mother and older sister.

“Benito informed us he would speak with every neighbourhood barrio, a type of captain who looks after local affairs. And that was it. We left.”

“I felt good that we had found that place,” says Tuy, “but honestly, it was like going through all those feelings again.

“From cloud nine, to hoping but not knowing. I really wanted to find him, but I honestly didn’t think it would happen.”

Thomas honoured his performance commitments and then flew home. Tuy had a few days to himself in Manila, before he also would return to the US.

Then there was a phone call from Benito.

“He told me that he’d found my father. The guy had been in Vietnam during the war, he was 65 and his name was actually Pantaleon Mance - similar sounding to the Fantaleon Sanchez my mom had recalled.

“I was told he would come visit me where I was staying [in Manila] at 8am the next day.”

The cold sweats that Tuy had experienced just six months prior in Sa Dec had returned.

After a sleepless night, Tuy put on a traditional Filipino shirt which he had bought, and waited patiently.

“It was quite different from meeting my Vietnamese mom,” he says.

“Because my agenda was that he had to prove to me that he was my father. If his answers were not correct, then the meeting would be over.”

As the two men chatted, it became clear that Pantaleon had the same agenda.

Questions were asked - and answers given. At some point, it became apparent that they were father and son.

“With Dad, it was just us - alone. Two people - two men - who could communicate. With Mom, it was a spectacle, and we could only talk in simple English and gestures.

“We rented a car and went to Calamba to meet my half-sisters, Tess and Faye, and then to Pantaleon’s friend’s house to celebrate.

“I remember the emotions overwhelming me in the car, which I think was quite hard for him.

“Two days later, he and his children saw me off at the airport. My life was in total upheaval - I had huge choices to make…”

The start of a new life

It wasn’t just in the Philippines where Tuy had relatives he never knew existed. In Vietnam, he also had an extended family.

In addition to his birth mother, Thi Be, he had one older full biological sister called Phuong and five younger half-siblings.

Tuy with some of his Vietnamese family, 1993

Thi Be’s second husband had recently died after being bitten by a snake in the rice fields. The family was in debt and lived in extreme poverty.

“They were living in a shack with a dirt floor and no electricity, whereas I was living a lottery life, going to art school in California,” he recalls.

Tuy's mother's house in Sa Dec, 1993

Tuy’s emotional ties with Vietnam and his relatives there strengthened.

For the next few years, his visits continued, and gradually his life became more focused on Vietnam than the US.

He built a small hotel near Ho Chi Minh City’s airport with some new Vietnamese friends. He also bought a house in Da Nang, and threw himself into learning Vietnamese.

On his trips to Sa Dec, Tuy says he always helped out - but never spoiled - his siblings. Slowly but surely, Thi Be and the family began to climb out of poverty.

Tuy also worked with his friend David Dang - one of the DeBolt family adoptees who had kept his original surname.

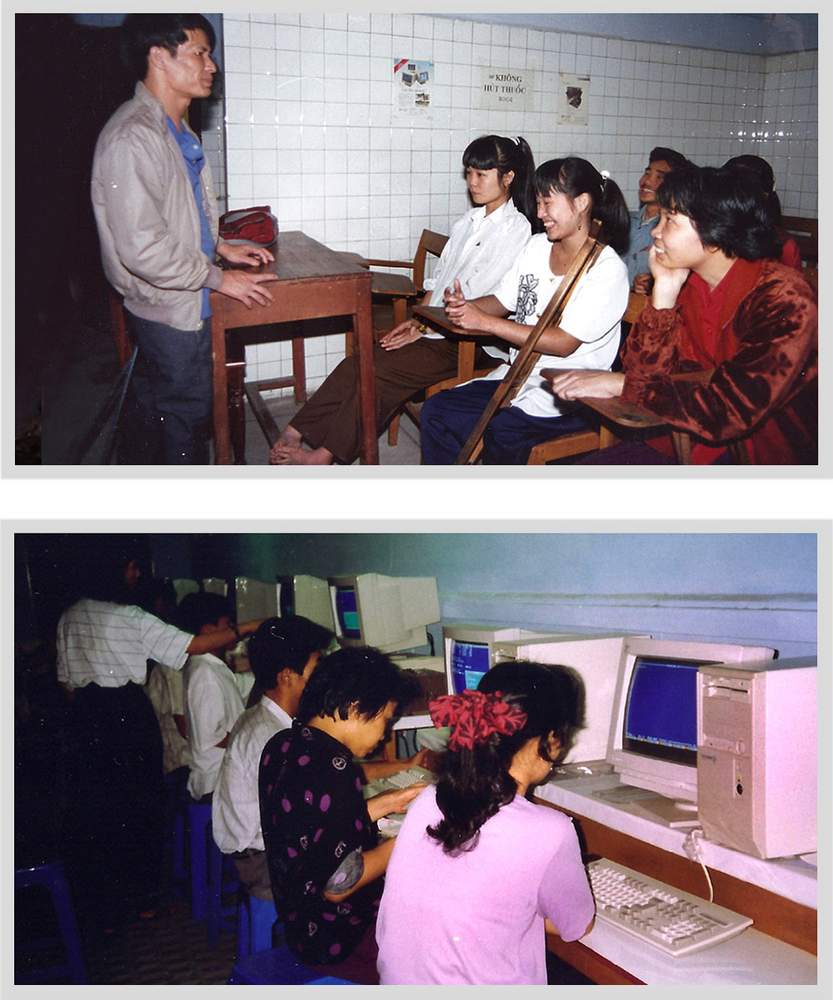

David had founded Ablenet - a non-profit organisation - with a mission to bring used desktop PCs from the US to Vietnam. A school was also set up to teach Vietnamese people with disabilities how to use - and programme - computers.

Ablenet classes

“Back then, if you were disabled you were a drain on the family,” says Tuy.

“You only had disabled workshops where the men would fix bicycles and the women were seamstresses or made arts and crafts.”

The Ablenet team meet Tuy's mother for lunch

Ablenet brokered US partnerships with some of Silicon Valley’s biggest names. But after a few years, partly because of increasing Vietnamese red tape, David closed the company.

And then in 1996, Tuy was hurt in a car accident in the US.

Clinton

Until the car accident, because of the lack of muscle strength in his legs, Tuy had been able to get around using crutches and leg braces.

But the accident forced him into a wheelchair permanently.

Tuy suffered a serious tear to a rotator cuff - the group of four muscles that come together as tendons, to hold the arm and shoulder together.

For two years, as the full extent of his shoulder damage became clear, Tuy was unable to travel outside the US.

But one afternoon in October 2000, Tuy got a call from David Dang, and was made an offer too good to turn down.

Because of their work with Ablenet, they were invited to join an IT delegation shadowing then US President Bill Clinton’s historic trip to Vietnam.

President Clinton would become the first serving US president to visit the country since Richard Nixon had travelled to South Vietnam in 1969.

IT delegation in Hanoi

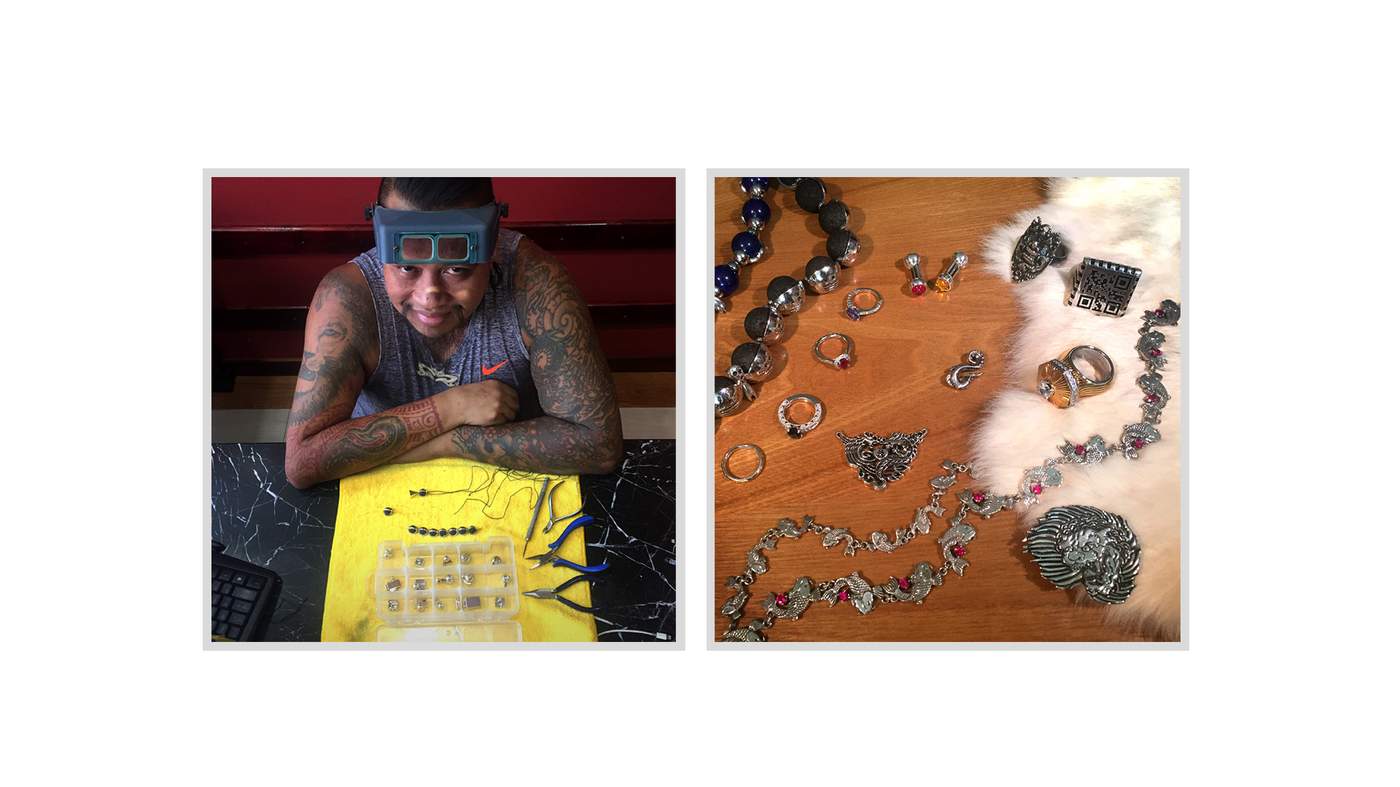

Tuy’s childhood creative streak had stayed with him and, since the mid-1990s, he’d been welding, building wheelchairs and designing jewellery.

Before he travelled, he made a line of commemorative pins which he planned to hand out to some of the presidential delegation.

Tuy admired Bill Clinton and it was his dream to meet him - but as the trip neared its end he hadn’t even been able to catch a glimpse of the president, other than on television.

On the last day of the visit, Tuy wheeled up to Ho Chi Minh’s City Hall on a whim. An IT business lunch was scheduled inside, and Tuy managed to blag his way in.

There was no lift, so Tuy crawled up the staircase pulling his chair behind him.

He mingled at the event for a time and then, because he was in his wheelchair, made his way out through a back room in the hope of finding an easier route to street level.

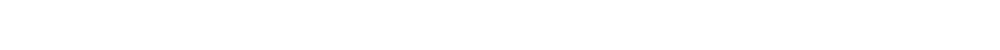

He suddenly found himself in the company of Senators John Kerry and Loretta Sanchez, and Transportation Secretary Norman Mineta.

Senator John Kerry with Tuy

Tuy being Tuy, he introduced himself and they chatted. He learned that President Clinton was about to give a speech in the lobby downstairs.

This was Tuy’s chance.

He raced down to the small area beside the main staircase and sure enough, people were setting up a podium. He parked his wheelchair in front and waited.

By the time Bill Clinton came out, the lobby was packed.

Tuy recalls how the president spoke about his hopes for “normalisation” between Vietnam and the US - and how the internet would help future Vietnamese businesses.

He also mentioned, says Tuy, how much he loved pho - a traditional Vietnamese noodle soup.

At the end, the president moved towards the front row of the crowd to shake hands.

With a big smile, Tuy grabbed the president’s hand with both of his - as is the way in Vietnamese culture when meeting someone important. Bill Clinton, in return, grabbed Tuy’s hands in the same fashion.

“I had a speech hastily made up in my mind,” says Tuy.

“I said that I had been watching Vietnam change for nine years, and I wanted to thank him for normalising relations.

“I told him I was born here, but had gotten polio and been adopted by a family in America and grown up in Berkeley.

“I went through my whole history as fast as I could, including the peace walk in ’91, and how I had found my Vietnamese family in ’93.

“I said it was due to his decision to normalise relations with Vietnam that so many more overseas Vietnamese could now return and be reunited with their families, their culture and their motherland.

“I thought he’d release my hand at this point, but instead he replied that it was people like me who made the whole trip worthwhile and he was glad to have done it.”

Tuy says the president then asked if he could have a photo with him - and called his official photographer over.

That long handshake made the national evening news that night in Vietnam.

Again - just like the day he was reunited with his birth-mother in Sa Dec - Tuy was a mini-celebrity.

The house of photographs

A hundred photos that tell a hundred stories are dotted along the walls of a large, modern house in Sa Dec.

They all revolve around Tuy’s adventures. It’s almost as if Forrest Gump had a real-life Vietnamese counterpart.

There are snapshots from when Tuy was first reunited with Thi Be - and the time he took her and his older sister to the Philippines in 2008 to be reunited with his biological father Pantaleon.

There are also pictures of the Vietnamese woman Tuy married in 2016.

Huong - or Katie as she is also known - was introduced to Tuy by a mutual friend after she had returned from a four-year business course in Japan.

She ended up working for Tuy at his custom jewellery business.

One thing led to another, and the couple fell in love.

Huong and Tuy

Now, for the first time in five years, Tuy’s entire extended Vietnamese family have come together for a feast.

It's being held in the home of Tuy's older sister Phuong.

Tuy built the house for his mother, Thi Be, but she now stays with him and Huong in their apartment in Ho Chi Minh City.

As I sit out back with Tuy, sipping steaming-hot Vietnamese green tea from tiny cracked jade-coloured porcelain glasses, he is keen to stress that a story of an adoptee meeting his biological parents is nothing new.

But the story that isn’t told, he says, is what comes next.

That’s the long process of integration, the challenges that face the adoptee as he or she tries to bond with their new family.

And likewise, the family getting to know their long-lost son, daughter, brother or sister.

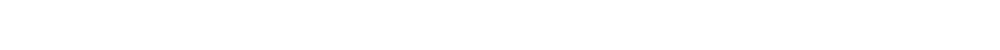

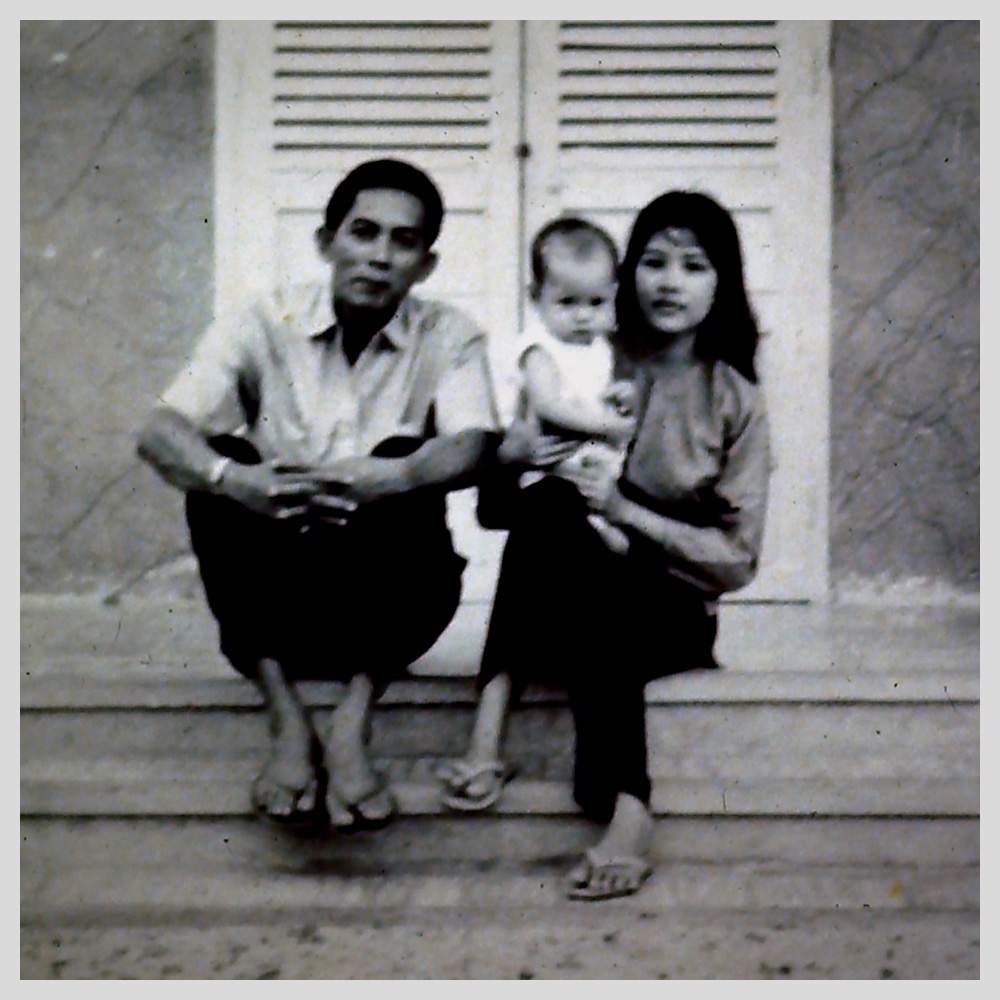

Tuy's biological father and mother - with baby Phuong

Tuy cherishes his extended family in Vietnam, the US and the Philippines - and in 2016, at his wedding, he fulfilled one of his life goals by bringing members from all three branches together.

Thomas, Thi Be, Huong and Tuy

After eating and drinking, the entire family sits together in the living room.

Tuy, his siblings, mother and aunts all speak of the trials they have faced together. His younger half-brothers and sister explain how scared they were of Tuy at first - and how hard it was to understand him and his character.

Tears flow freely as the whole family talk about their shared history.

“Tears of joy or sadness?” I ask. Without hesitation, and in unison, they respond “vui”.

Translated into English, it means “happiness”.