Da Vinci decoded: Secrets of Leonardo at a city near you

31 January 2018

Marking 500 years since Leonardo da Vinci's death, 144 of the Renaissance master's greatest drawings in the Royal Collection are being shared across twelve UK cities. WILLIAM COOK admires these extraordinary works displaying Leonardo's secrets of anatomy, engineering and art.

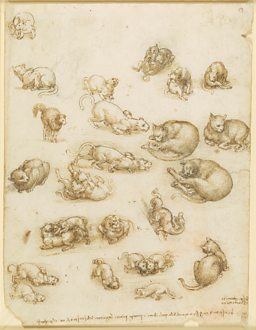

Leonardo da Vinci completed only about 20 paintings in his lifetime. Many of his greatest works were left unfinished, or destroyed. Yet he made hundreds of drawings covering an incredible array of subjects, from anatomy to botany, from sculpture to architecture, and now you can see a selection of them up close and personal, in a museum or gallery near you.

Leonardo's drawings cover an incredible array of subjects, from anatomy to botany, from sculpture to architecture.

Her Majesty the Queen owns around 550 Leonardo drawings, a collection that’s been in the Royal Family ever since the 17th Century.

Usually they’re tucked away at Windsor Castle, but this summer, to mark 500 years since Leonardo’s death, around 200 will be displayed at the Queen’s Gallery in Buckingham Palace (a smaller version of this exhibition will then travel to the Queen’s Gallery in Holyroodhouse in the autumn).

But you don’t need to wait until summertime to see some of these drawings. Ahead of the Buckingham Palace show in May, twelve museums and galleries all around the UK are mounting their own mini-exhibitions, each comprising twelve drawings from the main collection.

How the Queen came to own this priceless haul is a bit of a mystery. When Leonardo died in 1519, he left the contents of his studio to his pupil, Francesco Melzi. When Melzi died, around 1570, Leonardo’s drawings were acquired by a sculptor called Pompeo Leoni, who took them to Madrid.

Leoni divided these drawings into two albums. After Leoni died, in 1608, one album ended up in the Biblioteca Ambrosiana in Milan; the other was bought by Thomas Howard, Earl of Arundel (it may have been brought to Britain by Charles I, who went to Madrid in 1623 to find a bride and came back with a load of art instead). The album in Milan is bigger, but the one that Howard bought is the most comprehensive collection, by far.

We know Howard had these drawings in 1630, but by 1690 they were in Whitehall Palace, in the royal collection of William III. How did they end up there? No-one knows for sure, but the most likely explanation is that they were given to Charles II by Howard’s grandson, the Duke of Norfolk, to curry favour with the Merry Monarch after the Restoration.

Until the late 19th Century, when the Windsor collection was first published in reproduction, Leonardo was really a semi-mythical figure.

Nobody paid much attention to these drawings until the 1830s, when they wound up in the new Royal Library at Windsor Castle. Here at Windsor they were properly catalogued, the accompanying manuscripts were transcribed, and only then did their true importance finally emerge.

“Most of what we know about Leonardo comes from the Windsor Collection”, says Martin Clayton, Head of Prints & Drawings at the Royal Collection, and the curator of this show.

“Although it was known about, and was mentioned by early biographers, it isn’t until the late 19th Century that this collection is first published in reproduction and the notes are translated. Until that point, Leonardo was really a semi-mythical figure.” His Last Supper (not the Mona Lisa) was his only painting that was widely known.

So what makes these drawings so special? Above all, it’s their sheer quality. A lot of artists’ drawings are merely vague outlines for future projects. A lot of these drawings are preparatory studies, but Leonardo is such a brilliant draughtsman that even his roughest doodles are remarkable. “Leonardo used drawing as a way of investigating the world,” says Clayton.

These drawings are in fantastic condition – as if they were drawn yesterday.

If these drawings were by any artist, they’d be well worth seeing, but the fact that they’re by Leonardo makes them uniquely precious. There are so few Leonardo paintings, his drawings have added worth. Some are outlines for works which were never completed, or which no longer survive. Others are finished artworks in their own right.

“These drawings are in fantastic condition – as if they were drawn yesterday,” says Clayton.

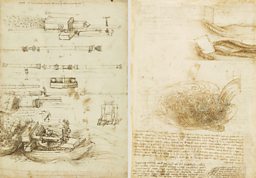

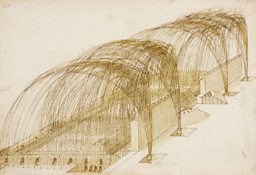

The other thing that sets them apart is their extraordinary range. It’s like leafing through an encyclopedia. He wrote illustrated treatises on everything from the flow of water to the growth of plants. He drew maps and landscapes, machines and weapons, even costumes for masquerades. He planned a canal for the River Arno which would link Florence to the sea.

Not all of da Vinci's designs stand up to 21st Century scrutiny. His flying machines couldn’t have flown – he didn’t understand aerodynamics; his gunboat would have capsized the moment its gun was fired.

Each of these compact exhibitions contains several masterpieces, drawings that are so precise and powerful.

However, even his unworkable ideas were visionary, and for every madcap scheme he came up with plenty that made perfect sense. He performed 30 dissections in his lifetime, making discoveries about the human body centuries ahead of his time.

What you’ll see in your local gallery in February is only a small selection, but each of these compact exhibitions contains several masterpieces - enough to whet your appetite ahead of the show in London in May.

Yet, on second thoughts, maybe an exhibition of 12 Leonardo drawings is an even better idea than an exhibition of 200? These drawings are so precise and powerful, you shouldn’t hurry past them.

Rather than rushing through them all this summer, far better to savour a dozen at your leisure, and marvel at the immaculate draughtsmanship of this amazing all-rounder.

”What we know about Leonardo today, how we think of him as the great Renaissance Man, who was equally skilled in all areas - that really is a modern understanding,“ says Clayton. ”So much of what he attempted in his life was never completed. It’s only surviving in the drawings.“ And it’s these drawings which made his reputation as the ultimate Renaissance Man.

Leonardo da Vinci – A Life in Drawing is at the following venues from 1 February to 6 May 2019.

And then at The Queen’s Gallery, Buckingham Palace, London from 24 May to 13 October 2019, and at The Queen’s Gallery, Palace of Holyroodhouse, Edinburgh from 22 November 2019 to 15 March 2020.

A Life in Drawing - Venues

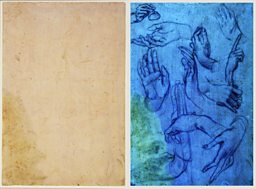

Hidden Leonardo revealed under UV light

A new light on Leonardo

Andrew Graham-Dixon views drawings by Leonardo da Vinci that have been lost for centuries.

Royal Collection highlights on BBC Arts

-

![]()

King of the collectors

An exhibition reunites the treasures amassed by Charles I for the first time in 370 years.

-

![]()

Art as power tool

How Charles II, the 'Merry Monarch', overruled austerity to project power through art.

-

![]()

The Padshahnama

This extraordinary work of Mughal painting was acquired by George III.

-

![]()

Royal armour

An incredible suit of armour created for Henry, Prince of Wales in 1608.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms