Wanting to die at 'five to midnight' - before dementia takes over

- Published

It's not unusual for Dutch patients with dementia to request euthanasia, but in the later stages of the disease they may be incapable of reconfirming their consent - one doctor is currently facing prosecution in such a case. But fear of being refused is pushing some to ask to die earlier than they would have liked.

Annie Zwijnenberg was never in any doubt.

"The neurologist said: 'I'm sorry, but there's no way we can mistake this - it's Alzheimer's," says Anneke Soute-Zwijnenberg, describing the moment her mother was first diagnosed.

"And she said: 'OK, then I know what I want.'"

Anneke's brother Frank chips in: "Maybe she hesitated for five seconds, and said: 'Now I know what to do.'"

They both knew she was referring to euthanasia.

Frank and Anneke (second and third left) during their mother's final moments

You could say Annie's story is a textbook case of how euthanasia is supposed to happen in the Netherlands - with very consistent and clear consent. But there are other cases where the patient's consent is less consistent, and at the final moment, less clear.

Annie's story was featured in a film called Before It's Too Late by the Dutch director, Gerald van Bronkhorst. In the documentary viewers follow her journey through Alzheimer's, ending in her death by euthanasia at the age of 81.

They see a proud woman who brought up three children alone, who enjoyed mountain climbing and had a strong religious belief, laid low by dementia.

"I used to go climbing or skiing or whatever," says Annie in the film. "In the village they said, 'That Annie, she's always on the go.' I'd put my rucksack on in the morning and start hiking. I'd walk all day. Now I can't do anything. I get confused all the time."

Euthanasia and the law

Euthanasia is the act of ending a person's life to relieve suffering - as distinct from assisted suicide (also known as assisted dying), which is assisting a person to kill themselves

Euthanasia is legal in Belgium, Canada, Colombia, Luxembourg and the Netherlands, while assisted suicide is permitted in Switzerland and a handful of US states

In England and Wales it is possible to make an advance decision, external (an advance directive, external in Scotland) to refuse a specific type of treatment in the future if you lose capacity to make the decision for yourself

The NHS says withdrawing life-sustaining treatment because it's in the person's best interests is not euthanasia and can be part of good palliative care

In July 2018 the Supreme Court of the United Kingdom ruled that legal permission is not required to withdraw treatment from patients in a permanent vegetative state

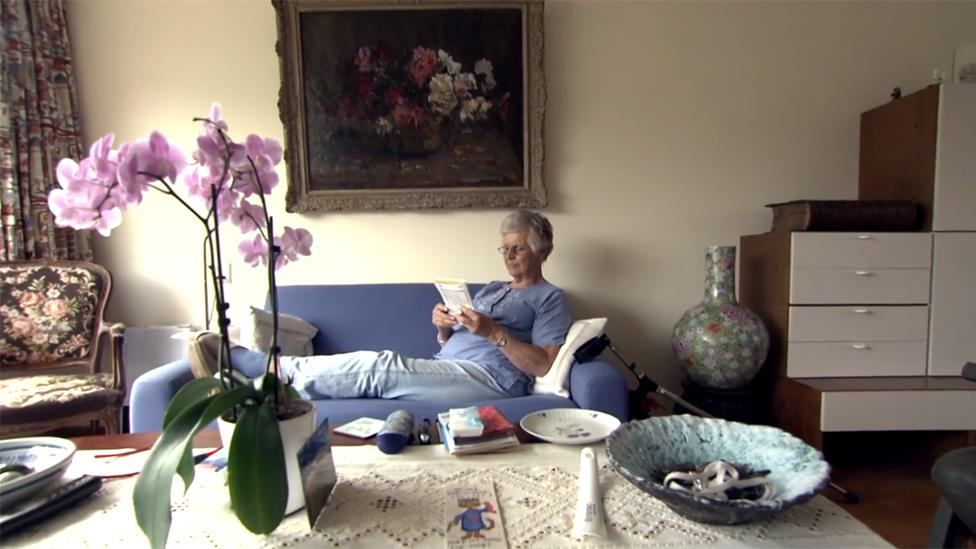

Annie wanted people to understand her decision, so she allowed the camera to film on the day she died.

She is shown sitting on the sofa, looking relaxed and positive. Her three children are with her, joking with the two doctors who've arrived to carry out the euthanasia about a special meal they had the previous night.

"We went to a three/four-star restaurant," Frank tells me later.

"I asked her, 'What do you want to do before you die?' We had a beautiful meal, laughed and cried. There was no tomorrow that evening. It was so special.

"But then you go home. It was very hard to get any sleep the night before."

Anneke describes finding a letter that her mother wrote that night.

"She wrote a letter to God, asking him to take care of her children. She knew that if there was a God it would be a really warm forgiving God."

Frank adds: "She said, 'It's a pity I can't send an email back to my children to tell them what it's like.'"

The film shows the doctor taking great care to make sure that Annie is fully aware that she is choosing to die by euthanasia. He asks her several times if she is sure she knows what she is doing.

"You're sure you want to drink the mixture I'll give you?" the doctor asks. "You know it will put you to sleep and you won't wake up again?"

Annie says: "I thought it through once again last night, from start to finish and back, and in the end this is what I want. Purely for myself. This is what's best for me."

She does not hesitate when she is handed a glass of clear liquid, containing a lethal dose of sedative. She drinks it, complaining only about the bitter taste.

Her family is shown hugging her as she goes to sleep for the last time.

"She drank the cup," remembers Frank later. "But it took a while."

"The sleep was getting deeper and deeper," adds Anneke. "It was very gentle."

But a couple of hours went by and Annie was still sleeping. This led to a surreal scene, described to me by Gerald van Bronkhorst, who was filming.

"She was asleep on the couch, and then she started snoring. And the family started to say: 'I'm hungry, shall we have a sandwich?' So we're all chewing around this lady, who's sleeping on the couch, and dying. But this shows how normal life takes over, even in a situation like this."

Worried that Annie might actually wake up, the doctors eventually gave her a lethal injection.

"It was 20 seconds, and then she was gone," says Frank.

Frank and Anneke say they always supported their mother in her decision, despite any reservations they felt about it.

"It's hard to see your mother die from euthanasia, but it was not our decision - it was her decision," says Anneke.

"There is no right or wrong decision. It's hard to decide you want to die but it's as hard to decide, I think, that you want to live. She hated it when someone said: 'It's so brave that you made this decision.' She said choosing to live with dementia is just as brave."

Frank adds: "A good friend of mine said, 'You have to stop your mother - as a son you have to stop her.' I said, 'No I'm not going to, I support her.' His mother said [to me], 'You're killing your mother, you're murdering your mother if you go on with this…' It's hard to hear."

Arguments like this are common among families and friends and reflect the wider debate which began in the Netherlands in the 1970s, when doctors first started carrying out so-called "mercy killing" fairly openly. The arguments continued in the run-up to the legalisation of euthanasia in 2002, and have never really stopped.

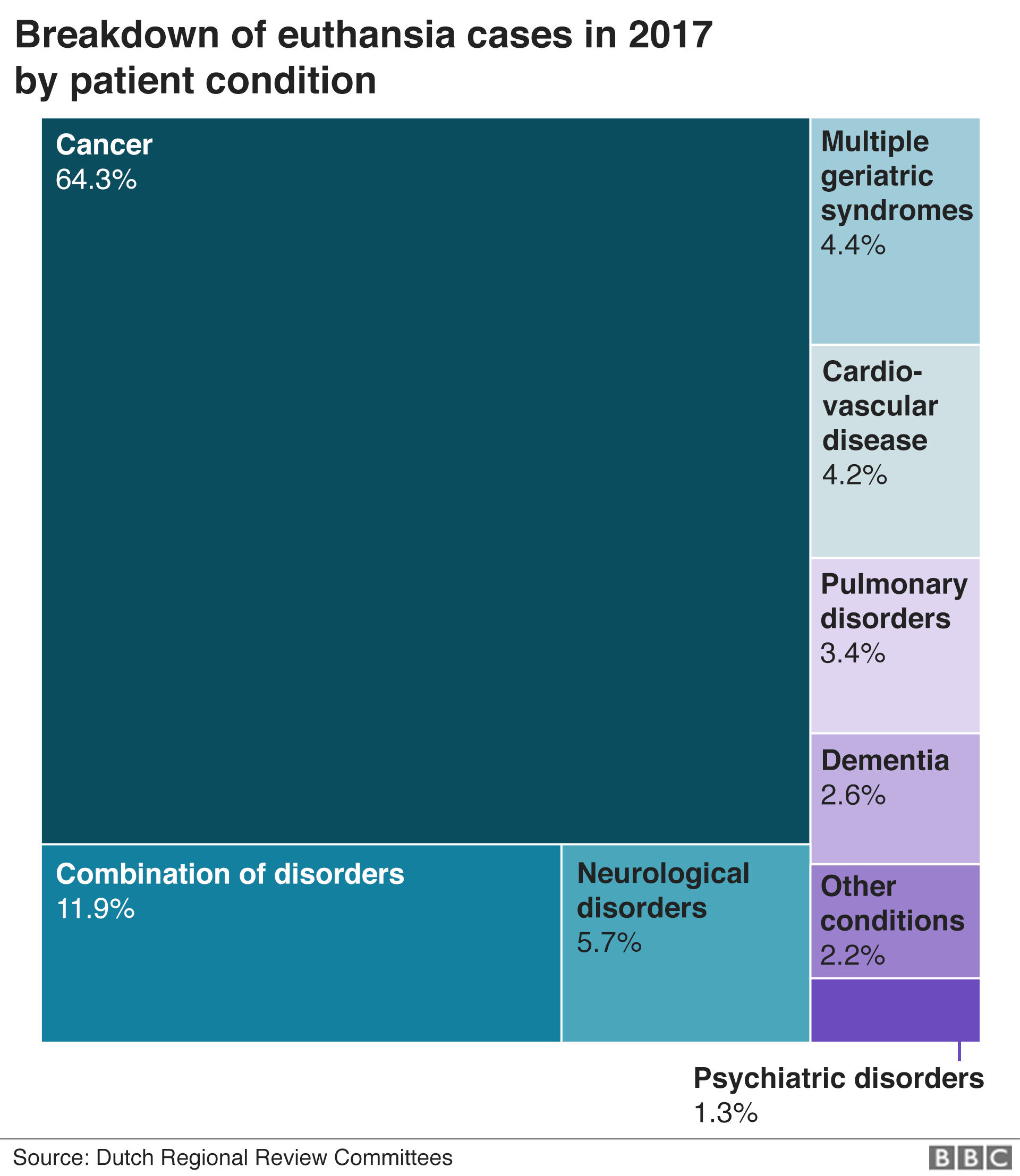

The number of those opting for euthanasia has grown steadily, particularly in the past 10 years. In 2002, the Dutch authorities were notified of 1,882 cases; 15 years later the figure was 6,585.

In order to satisfy the law on euthanasia, patients must convince a doctor that their decision is completely voluntary, that their life has become, or will become, one of "unbearable suffering without prospect of improvement", and that there is "no reasonable alternative". An independent assessment must then be made by another doctor.

The first recorded case of a patient with dementia being given euthanasia came about in 2004, two years after the law changed.

But euthanasia cases involving dementia patients almost always take place in the earlier stages of the disease, because it's hard to convince a doctor that the patient has the capacity to understand their decision to die in the later stages.

In 2017, 166 early-stage dementia patients died by euthanasia, and only three with late-stage dementia.

Despite this, medical ethicist Berna van Baarsen believes that a shift is under way and that in future there will be more.

She used to sit on a committee that reviewed every case of euthanasia in one region of the Netherlands but resigned, saying that troubling cases were being approved too easily.

"I have seen the shift," she says. "The problem is that the shift is very difficult to catch. But it is happening. It's happening under your nose, and in the end you realise there has been a shift."

She thinks there is an over-reliance on written declarations, or living wills, which patients who might want euthanasia often give to their doctor in the early stages of a disease.

"You can write down what your fears are. What you don't want to experience. But it is a wish. It is an expression of fear, and as we know, people change.

"In the beginning they say: 'Oh no, I don't want to live in an old people's home.' Or, 'I don't want to be put in a wheelchair,' and it happens. People always find ways to cope. That's a beautiful thing about being human."

So she argues that before helping someone to die, doctors must always check that this is still the patient's wish. And with late-stage dementia patients, this is not always possible.

"If you can't talk to a patient, you don't know what the patient wants," she says.

But if Berna van Baarsen is right that the pendulum has been swinging in favour of euthanasia for patients with late-stage dementia, the prosecution of a doctor involved in one such case may push it back in the opposite direction.

The case involved a 74-year-old woman who had signed a written declaration saying she wanted euthanasia, but only when she said she was ready. And she had also said, at other times, that she did not want to die by euthanasia.

The doctor, who worked in a nursing home, put a sedative into the woman's coffee without telling her. Then the woman woke up while the doctor attempted to give her a lethal injection.

She had to be restrained by relatives while the euthanasia was completed, although the level of restraint used is disputed.

Find out more

Listen to the documentary Living and Dying with Alzheimer's on BBC Sounds

Jacob Kohnstamm, co-ordinating chairman of the Dutch review committees, which examine every euthanasia case, says it is clear the doctor overstepped the mark.

"The commission said the written declaration wasn't good enough, and the doctor should have stopped the procedure the moment the patient got up," he says.

The committee ruled that the doctor had not acted with due care, and referred the case to prosecutors.

The case will be watched closely when it comes to trial because it may help to clarify the circumstances when dementia patients can die by euthanasia.

But while for many doctors this will be welcome, it is an unnerving prospect for those who are prepared to carry out euthanasia even on people with advanced dementia - such as Annie Zwijnenberg's doctor, Constance de Vries.

She is content to end the lives of patients who may find it difficult to express their wishes, as long as they were always very clear about their wishes when they could express them.

Constance de Vries: "I try to be very, very, very sure about what I'm doing"

It's important to have a long-term relationship with the patients and their families, she says, to enable her to talk to them about their written declaration, and observe over a long period of time an unwavering desire for euthanasia.

She tells me about one such case.

"The lady was very unhappy; she was crying, and yelling, and not eating, and not sleeping, and aggressive to other people. When you saw her, you saw how unhappy she was. And she always had it in the statement: 'When I don't recognise my grandchildren any more, then I want to die.'"

As the moment when she could no longer recognise her grandchildren had arrived, Constance de Vries proceeded with euthanasia, with the support of the woman's family.

"When I gave her a glass of fruit juice, I said, 'When you take it, you will sleep forever.' She looked at her daughter, and the daughter said, 'It's OK mum.' And she took it. I don't know if she did understand fully, but I know what we did was OK, so unhappy was she."

I ask her if the first prosecution of a doctor for ending a patient's life by euthanasia makes her worried about being involved in such cases?

"This is making me worried, yes," she says. "I'm a little bit afraid of the judgement afterwards. So I try to be very, very, very sure about what I'm doing."

But does she have any intention of stopping?

"No," she says, adamantly.

She does concede, though, that the case may make it harder for patients with late-stage dementia to get euthanasia in future. And if this happens, it could also have a knock-on effect for those with early-stage dementia who want euthanasia at some point in the future.

Many of them already worry that if they wait too long they'll be denied it.

The fear has become so commonplace that a shorthand phrase has been adopted for the perfect time to have euthanasia - "five to midnight". Just like Cinderella, everyone wants to wait until the last possible moment before they leave the party - until five to midnight - but many feel that it's too risky to leave it that long.

It's the one regret Anneke and Frank express about the death of their mother, Annie.

"She was very afraid that even when she had the law on her side, or she had the doctors on her side that there would be a point that somebody would say: 'OK, but sorry you're too far gone now, you can't make this decision any more, so sorry you're too late,'" Anneke says.

Annie herself talks about it in Gerald van Bronkhorst's film, which alludes to her fear in its title, Before It's Too Late.

"Yesterday I spoke to a former neighbour on the phone," Annie says. "She said, 'But I don't understand. You can still do everything can't you?' I said, 'Well the point is, first of all I can't. And second, if I wait until the moment has come to stop it'll be too late. I won't be allowed to do euthanasia any more.'"

Images from Before It's Too Late courtesy of Gerald van Bronkhorst

You may also be interested in:

In January 2018 a young Dutch woman drank poison supplied by a doctor and lay down to die. Euthanasia and doctor-assisted suicide are legal in the Netherlands, so hers was a death sanctioned by the state. But Aurelia Brouwers was not terminally ill - she was allowed to end her life on account of her psychiatric illness.

Read: The troubled 29-year-old helped to die by Dutch doctors

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, YouTube, external and Twitter, external.