#Vote100Books: 7 novels by women that deserve your attention

24 May 2018

To mark 100 years since some women in Britain first got the vote, the Hay Festival has assembled a public-voted list of 100 books written by women in the past century. As the list is revealed, BBC Arts spotlights seven titles that deserve to be on everyone's reading list.

Homegoing by Yaa Gyasi (2016)

Homegoing weaves a spectacular epic . . . Gyasi gives voice not just to a single person or moment, but to a resonant chorus of eight generations.Los Angeles Review of Books

Yaa Gyasi’s debut novel opens in Ghana in the 18th Century with two half sisters whose lives diverge down very different paths: Effia is married to a slave trader, while Esi is sold into slavery and transported from West Africa to America.

The ambitious novel travels from the Gold Coast to the slave plantations of Mississippi and the dive bars of Harlem, introducing a new descendant with each chapter. The consequences of the sisters’ fates resonates throughout the bloodline right up to the present day.

Homegoing's title comes from the belief that death allowed an enslaved person’s spirit to travel back to Africa. The book scrutinises the role of West Africa in the slave trade, exploring the trans-Atlantic legacy of those who were taken and those who remained.

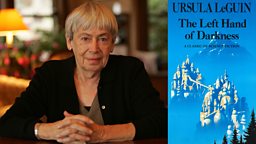

The Left Hand of Darkness by Ursula K Le Guin (1969)

No single work did more to upend the genre’s conventions than The Left Hand of Darkness.The Paris Review

Le Guin is described by Penguin as the “queen of science fiction”. Her 1969 novel The Left Hand of Darkness is set on Winter, a frozen planet populated by genderless beings. Its occupants live in brutally harsh conditions, and take on male or female characteristics once a month when they are in heat. Anyone can become pregnant.

The novel combines science fiction with a classic journey narrative, exploring isolation and exile as two individuals, male visitor from Earth Genly Ai and Winter occupant Estravan, undertake a painfully slow 800-mile journey across the frozen landscape.

Le Guin called Darkness a “thought experiment” in sexual politics. It was the first book written by a female author to win Best Novel at the Hugo Awards, the prestigious literary awards for science fiction.

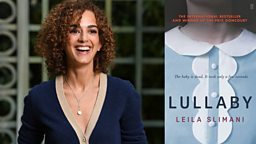

Lullaby by Leïla Slimani (2016)

A dark, unnerving exploration of class and conscience, power and impotence, and how the people with nothing to lose are the most dangerous people of all.The Express

Leïla Slimani’s Lullaby, translated from the French by Sam Taylor, is an unflinching psychological thriller about a professional couple who hire a (seemingly perfect) nanny to look after their two young children and manage their home.

Infanticide takes place in the shocking opening paragraphs, before the book flashes back to the events leading up to the crime. It interrogates moral, social and economic deprivation in Paris and explores society's attitudes to motherhood and identity.

Leïla Slimani knew her book would invite controversy, stating that she was tackling two taboos: child murder and the place of the mother today. In 1916 it won the Prix Goncourt, a French literary prize awarded to the author of "the best and most imaginative prose work of the year".

Persepolis by Marjane Satrapi (2000)

Striking a perfect balance between the fantasies and neighborhood conspiracies of childhood and the mounting lunacy of Khomeini’s reign, she’s like the Persian love child of Spiegelman and Lynda Barry.Salon

Persepolis is an autobiography depicting Marjane Satrapi’s childhood in Iran. Satrapi experienced the overthrow of the Shah’s regime, the triumph of the Islamic Revolution and the brutal effects of the Iran-Iraq War, all in less than a decade.

The graphic novel blends the personal – her family history, her experiences of changing to a gender-segregated school and wearing a veil – with the wider political issues of her homeland, told using simple and stark black and white images.

Drawing on her life in Tehran from age six until she turned 14, Persepolis offers a child’s perspective of living through war, religious upheaval and revolution. It sets out to both challenge the Western view of modern Iran and to represent the Iranians who suffered under various repressive regimes.

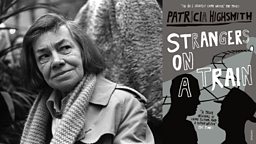

Strangers on a Train (1950)

A writer who created a world of her own - a world claustrophobic and irrational which we enter each time with a sense of personal danger.Graham Greene

Strangers on a Train is a novel often eclipsed by its silver screen adaption, Alfred Hitchcock’s highly successful film of the same name. Highsmith’s debut novel is the story of two men, Guy Haines and Charles Bruno, who meet by chance. Bruno suggests an extreme solution to his travel companion’s relationship problem – he will murder Haines' wife, if he returns the favour and murders Bruno's father.

When his wife is discovered dead, Haines knows Bruno is the guilty party. The pair become locked in a thrilling game of cat-and-mouse as Bruno insists that Haines upholds his part of the bargain. Highsmith creates a dark, shocking and suspenseful work of noir fiction that artfully displays a fascination with the evil lurking behind the mundane.

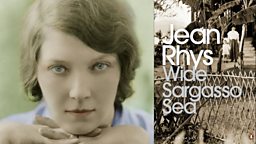

Wide Sargasso Sea (1966)

Wide Sargasso Sea is a prequel and response to a novel often itself found on lists of great works, Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre. Rhys explores the story of Mr Rochester’s first wife, Bertha, referred to in Brontë’s classic as “the madwoman in the attic”.

Rhys looks shockingly closely at the mélange of racism, sexism, classism and personal sadism which drives Rochester.Bidisha

The book humanises Bertha (whose real name, Antoinette, is changed by the unnamed Mr Rochester) and gives voice to her experience of life in the West Indies and her forced marriage to the Englishman, in a time and space where patriarchal laws made her and the women around her entirely dependent on men.

The novel draws attention to the colonialism and slave trade by which both Mr Rochester and Antoinette became wealthy, and explores the tensions of race, colour and status in 1830s Jamaica. It is scattered with foreboding as to the fate that awaits Antoinette in England at the hands of a husband who exploits her physically, emotionally and psychologically.

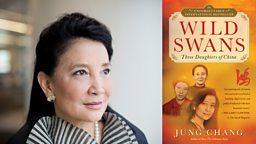

Wild Swans by Jung Chang (1991)

It is impossible to exaggerate the importance of this book.Mary Wesley

Wild Swans is an epic family memoir that tracks the staggeringly different lives of three generations of women living in a rapidly changing China.

Jung Chang’s grandmother, when still a teenager, was given as a concubine to a warlord General. Her mother, daughter of the warlord, was active in the communist movement during the Chinese Civil War and became, along with her husband, a high-ranking official in the Communist Party. Chang herself grew up in the privileged circles of China’s Communist elite but experienced the horrors of the Cultural Revolution first hand when her parents were denounced and she was exiled.

Wild Swans uses the personal stories of one family to vividly illustrate the social and political turmoil of a country. It has been translated into 40 languages but remains banned in China.

The #Vote100Books List

There are multiple lists already in existence that lay claim to "the best 100 books" but they have always swayed in favour of the male author. The public-voted BBC Big Read featured just 35 titles by 27 female authors and The Guardian's 2015 list "The 100 best novels written in English" only included 21 titles by women. To mark the centenary of women winning the right to vote, Hay Festival and The Pool launched the #Vote100Books campaign with the aim of assembling a list of works by women that deserve more attention.

The #Vote100Books list contains several established great literary works (Maya Angelou’s I Know Why The Caged Bird Sings, Margaret Atwood's The Handmaid's Tale) as well as more unusual choices from well-known authors: Sylvia Plath’s Ariel is there but The Bell Jar is not; Agatha Christie's The Body in the Library is the thriller-writer's contribution to the list; A Greater Place of Safety by Hilary Mantel is included but there is no place for her two Booker Prize-winning novels.

With the only criteria for the #Vote100Books list being that books must be written by women, and written in the last 100 years, the final list is eclectic. It covers fiction, non-fiction, poetry, short stories and graphic novels, with children’s fiction (The Gruffalo by Julia Donaldson), recipe books (How to Eat by Nigella Lawson) and feminist manifestos (The Second Sex by Simone de Beauvoir) stacked side-by-side.

As with any selection of books there will always be omissions. To address this, the Hay Festival has assembled a panel of writers including Edith Hall, Shazia Mirza, Allison Pearson, Elif Shafak, Sharlene Teo and Gabrielle Walker to debate what should or shouldn't have been included at the Festival on Monday 28 May 2018.

View The List

-

![]()

The #Vote100Books List

View the list of 100 works by female writers in full, alongside descriptions of each work.