Morag Connelly watched as the bottle was dropped into the River Clyde.

The water was quite calm and as the bottle bobbed around on the surface, she wondered if it would make it out to sea.

Morag Connelly

Inside it she had sealed a copy of the dreadful story that had brought her and 24 others to Victoria Harbour in Greenock that Saturday afternoon in early April - the story of seven young stowaways, all but one of whom had been starved, brutalised and eventually abandoned on floating ice, thousands of miles from home.

John Paul - Morag’s great-great-grandfather - was one of them.

Unlike two of his young companions, he survived. But the horror of his experiences was passed down through the generations.

“If we ever complained about being cold in the winter my father would say, ‘Just think of John Paul, he walked on the ice in his bare feet,’” says Morag, a retired deputy headteacher.

“It was always something that was said in bad weather.”

Stowing away

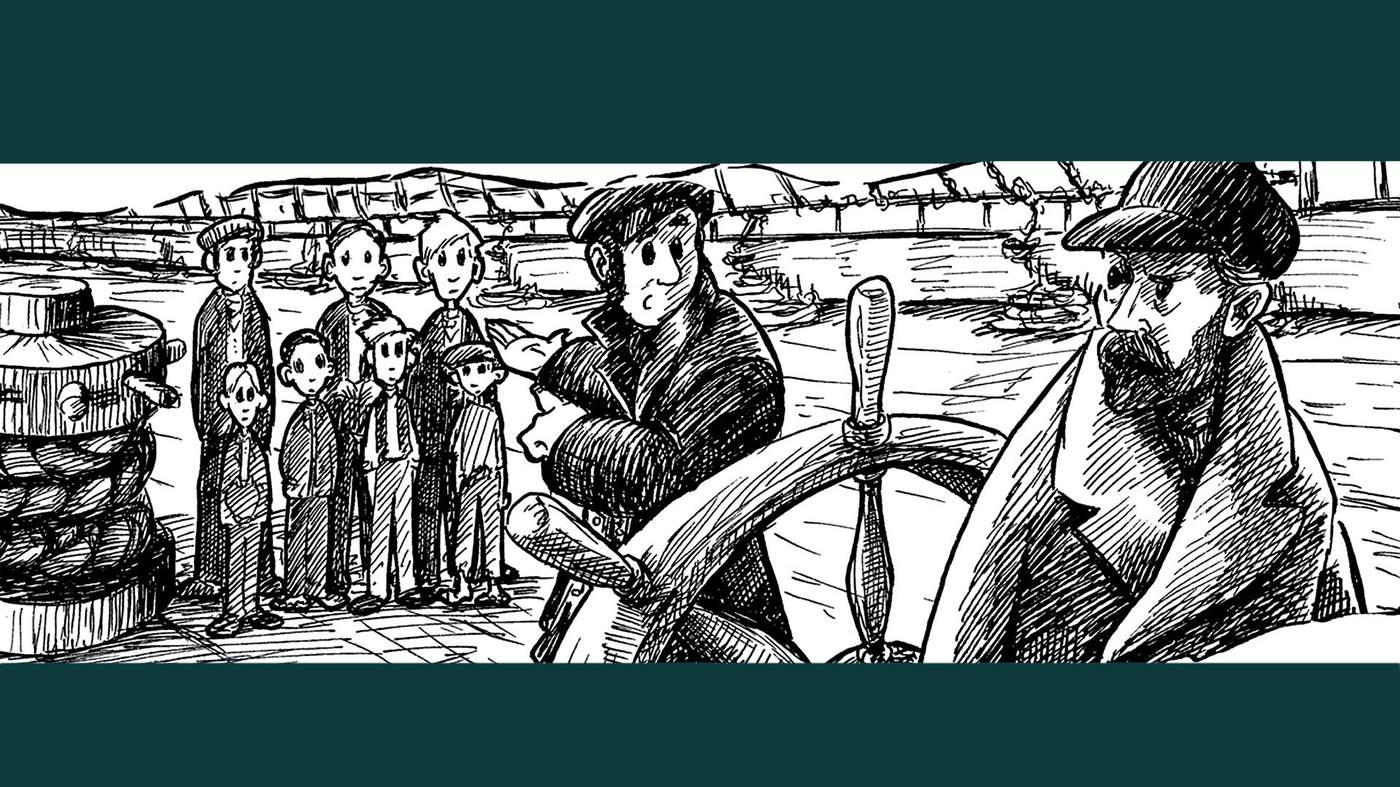

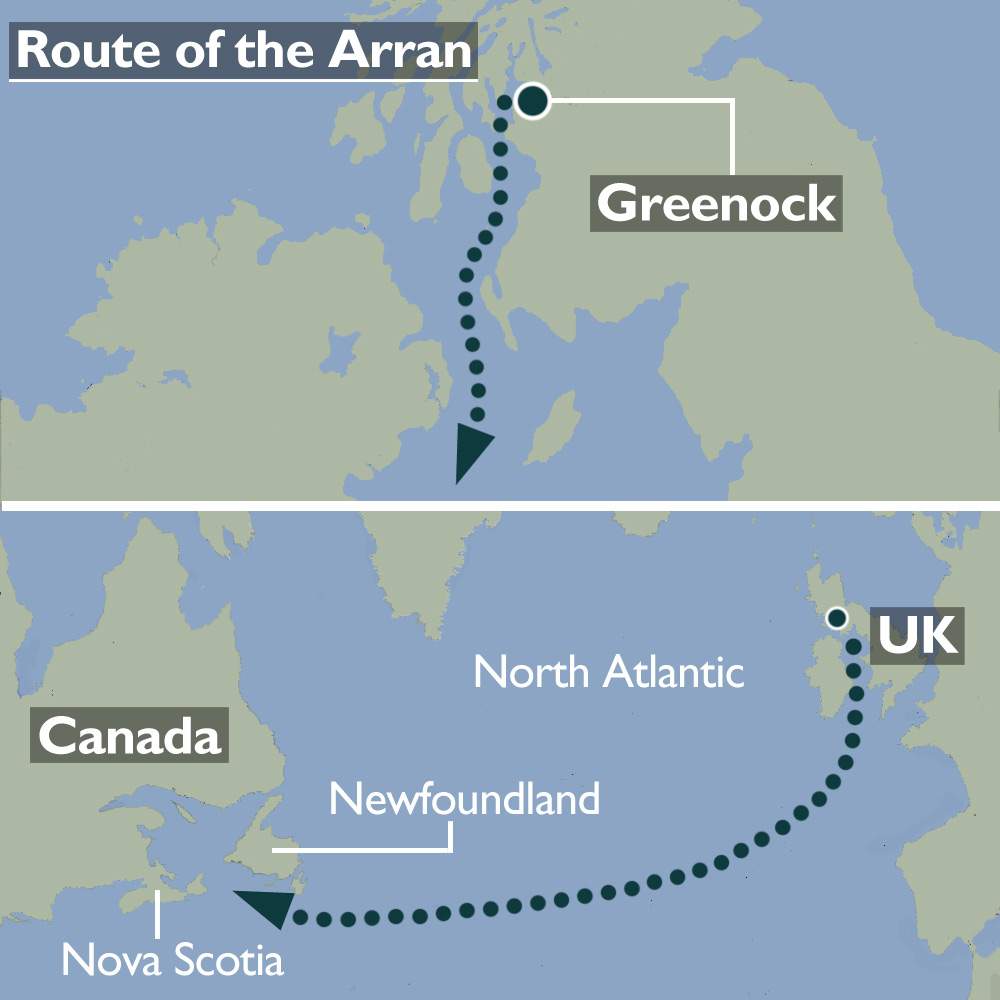

As a boy of 12, John Paul had hidden away on a ship called the Arran, which on 7 April 1868 sailed from the quayside where Morag and other descendants, including John Paul’s 90-year-old granddaughter, Ria, were now standing.

The ship was carrying a cargo of coal and oakum - a fibre made by painstakingly untwisting old ropes - and was heading across the Atlantic Ocean to the Canadian province of Quebec.

Nobody knows why John Paul and the others decided to stow away, but his descendants say it was common in those days for Greenock boys to smuggle themselves on to ships in the harbour, seeking adventure and hoping to escape from the poverty of their childhoods.

Ships were routinely checked for stowaways and any found would be sent back ashore on tugs - but John Paul wasn’t found.

The Arran sailed down the Firth of Clyde and into the Irish Sea towards the Atlantic.

Dry land was by now far behind and the tugs had long since cast the ship loose. As the ship’s carpenter prepared to batten down the hatches John Paul and another boy, 11-year-old Hugh McEwan, were finally discovered.

Then five more stowaways emerged.

It was too late to send them back.

‘A rarely told story’

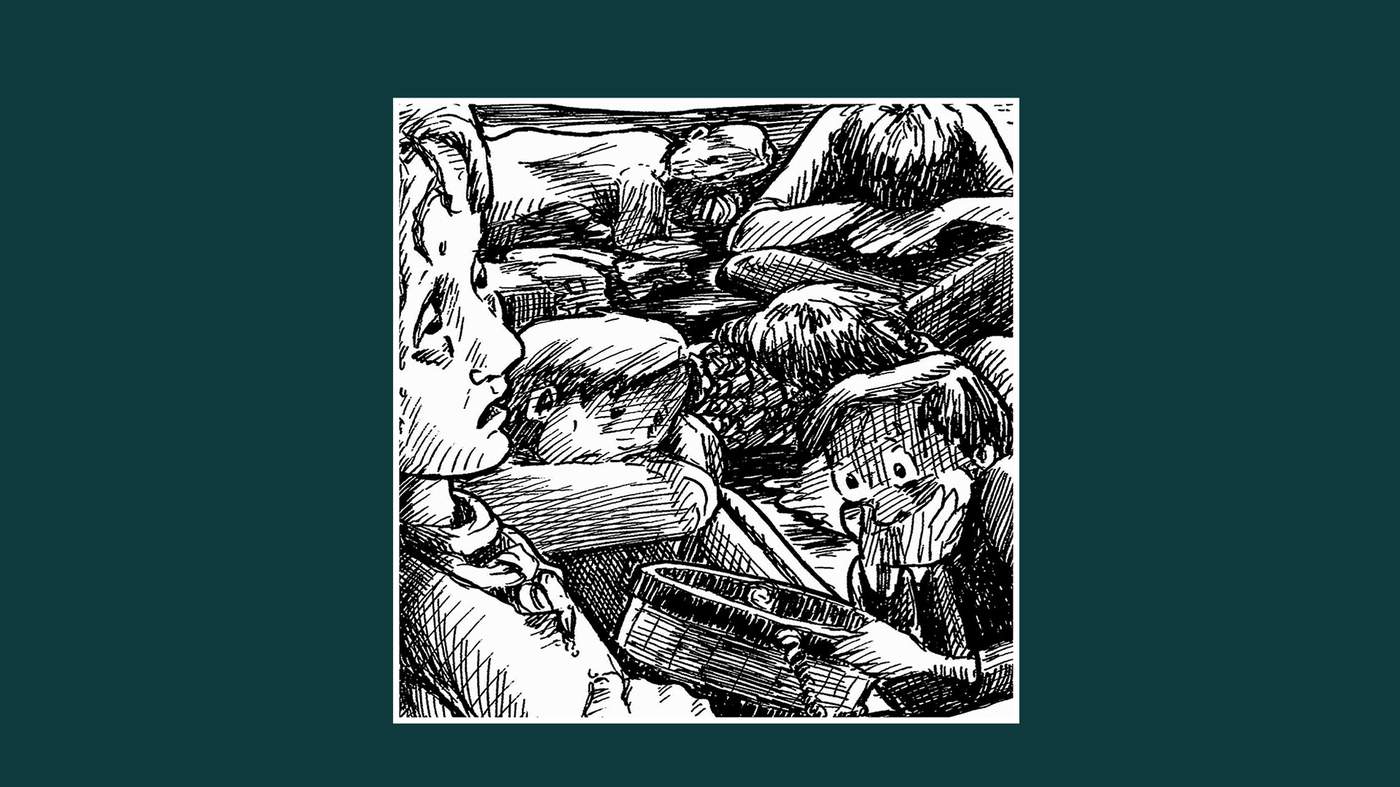

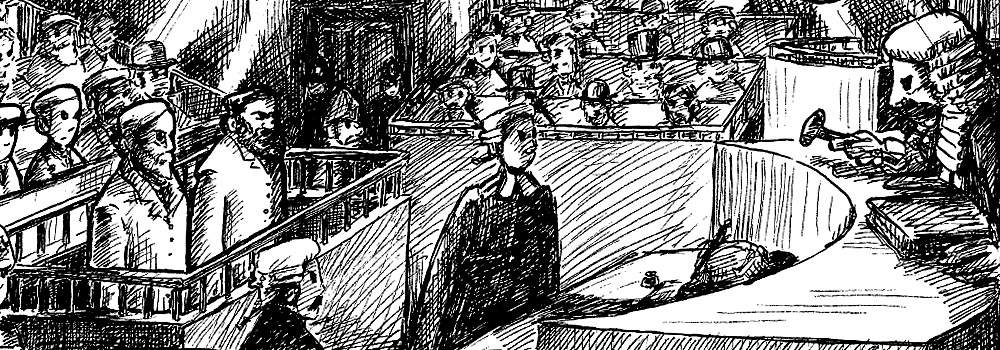

These illustrations come from a graphic novel created by pupils of Ardgowan primary school in Greenock, with Magic Torch Comics writer Paul Bristow and artist Mhairi M Robertson.

The aim was to bring the story to a new, younger audience. “We look at the folk tales and stranger things that are associated with the area - the stories that have fallen out of the telling,” Paul says.

From then on they were only given a few ship’s biscuits to eat each day, so that even with the few scraps slipped to them in kindness by the cook, and the potato and turnip peelings they scavenged here and there, they had barely enough to survive.

So they stole whatever they could lay their hands on from the ship’s stores - currants, oatmeal and more biscuits - but were heavily punished when caught.

Once, when a grain barrel was found to have been opened, they immediately fell under suspicion. As punishment they were handcuffed together and given nothing to eat for an entire day.

Hunger was not the stowaways' only problem. They were also unprepared for the harsh conditions of the North Atlantic.

“The boys were thinly clad, and were not able to stand the severe cold,” one of the ship’s crew wrote to his family in Greenock after the ship had reached Quebec, nearly two months later.

“The men could hardly stand it, let alone them. Two of the little ones had bare feet.”

John Paul was one of the boys without shoes, the other was Hugh McGinnes, also 12 years old.

The two of them would disappear below deck together to escape from the bitter cold, but whenever the ship’s mate realised they were missing he would drag them out and beat them.

The stowaways

- Hugh McEwan, 11

- John Paul, 12

- Hugh McGinnes, 12

- Peter Currie, 12

- James Bryson, 16

- David Brand, 16

- Bernard Reilly, 22

Another of the boys was singled out for particularly brutal treatment, which began when the crew and other stowaways complained that he was dirty.

“He made me take off my jacket, waistcoat, and shirt, leaving only my semmit [vest] on. The coil was about half an inch thick. The mate flogged me for about three minutes and the blows were very painful,” 16-year-old James Bryson said later.

“I was screaming. The mate made me strip off the rest of my clothing. I was then made to lie down on the deck.

“One of the crew was ordered to draw water in a bucket. Several buckets of water were thrown at me.”

“The weather was very cold. The captain then scrubbed me with a hair broom all over my body. The mate was standing over me with a rope in his hand, with which he threatened to strike me if I tried to run away.

“The mate then took the broom and scrubbed me harder than the captain. After the scrubbing was finished, I was ordered to the forecastle. I was naked at the time. When I had been there for about an hour my semmit was returned. I suffered very much from exposure.”

On another occasion, having been caught stealing currants from the ship’s store, James Bryson was lashed with the lead line - a rope with a lead weight at its end used to determine the depth of water - and then made to strip naked and sweep the decks.

A sailor called James Harley witnessed the torture.

“I saw Bryson's skin after he had been flogged and it resembled tartan,” he told an Edinburgh court months later, when the mate and captain were put on trial. “It was red and white.”

Bryson may have been the only one who was punished in this barbaric way, but all except one of the stowaways - 12-year-old Peter Currie, whose father was a friend of the ship’s mate - were regularly beaten.

From then on they were only given a few ship’s biscuits to eat each day, so that even with the few scraps slipped to them in kindness by the cook, and the potato and turnip peelings they scavenged here and there, they had barely enough to survive.

So they stole whatever they could lay their hands on from the ship’s stores - currants, oatmeal and more biscuits - but were heavily punished when caught.

Once, when a grain barrel was found to have been opened, they immediately fell under suspicion. As punishment they were handcuffed together and given nothing to eat for an entire day.

Hunger was not the stowaways' only problem. They were also unprepared for the harsh conditions of the North Atlantic.

“The boys were thinly clad, and were not able to stand the severe cold,” one of the ship’s crew wrote to his family in Greenock, after the ship had reached Quebec nearly two months later.

“The men could hardly stand it, let alone them. Two of the little ones had bare feet.”

John Paul was one of the boys without shoes, the other was Hugh McGinnes, also 12 years old.

The two of them would disappear below deck together to escape from the bitter cold, but whenever the ship’s mate realised they were missing he would drag them out and beat them.

The stowaways

- Hugh McEwan, 11

- John Paul, 12

- Hugh McGinnes, 12

- Peter Currie, 12

- James Bryson, 16

- David Brand, 16

- Bernard Reilly, 22

Another of the boys was singled out for particularly brutal treatment, which began when the crew and other stowaways complained that he was dirty.

“He made me take off my jacket, waistcoat, and shirt, leaving only my semmit [vest] on. The coil was about half an inch thick. The mate flogged me for about three minutes and the blows were very painful,” 16-year-old James Bryson said later.

“I was screaming. The mate made me strip off the rest of my clothing. I was then made to lie down on the deck.

“One of the crew was ordered to draw water in a bucket. Several buckets of water were thrown at me.”

“The weather was very cold. The captain then scrubbed me with a hair broom all over my body. The mate was standing over me with a rope in his hand, with which he threatened to strike me if I tried to run away.

“The mate then took the broom and scrubbed me harder than the captain. After the scrubbing was finished, I was ordered to the forecastle. I was naked at the time. When I had been there for about an hour my semmit was returned. I suffered very much from exposure.”

On another occasion, having been caught stealing currants from the ship’s store, James Bryson was lashed with the lead line - a rope with a lead weight at its end used to determine the depth of water - and then made to strip naked and sweep the decks.

A sailor called James Harley witnessed the torture.

“I saw Bryson's skin after he had been flogged and it resembled tartan,” he told an Edinburgh court months later, when the mate and captain were put on trial. “It was red and white.”

Bryson may have been the only one who was punished in this barbaric way, but all except one of the stowaways - 12-year-old Peter Currie, whose father was a friend of the ship’s mate - were regularly beaten.

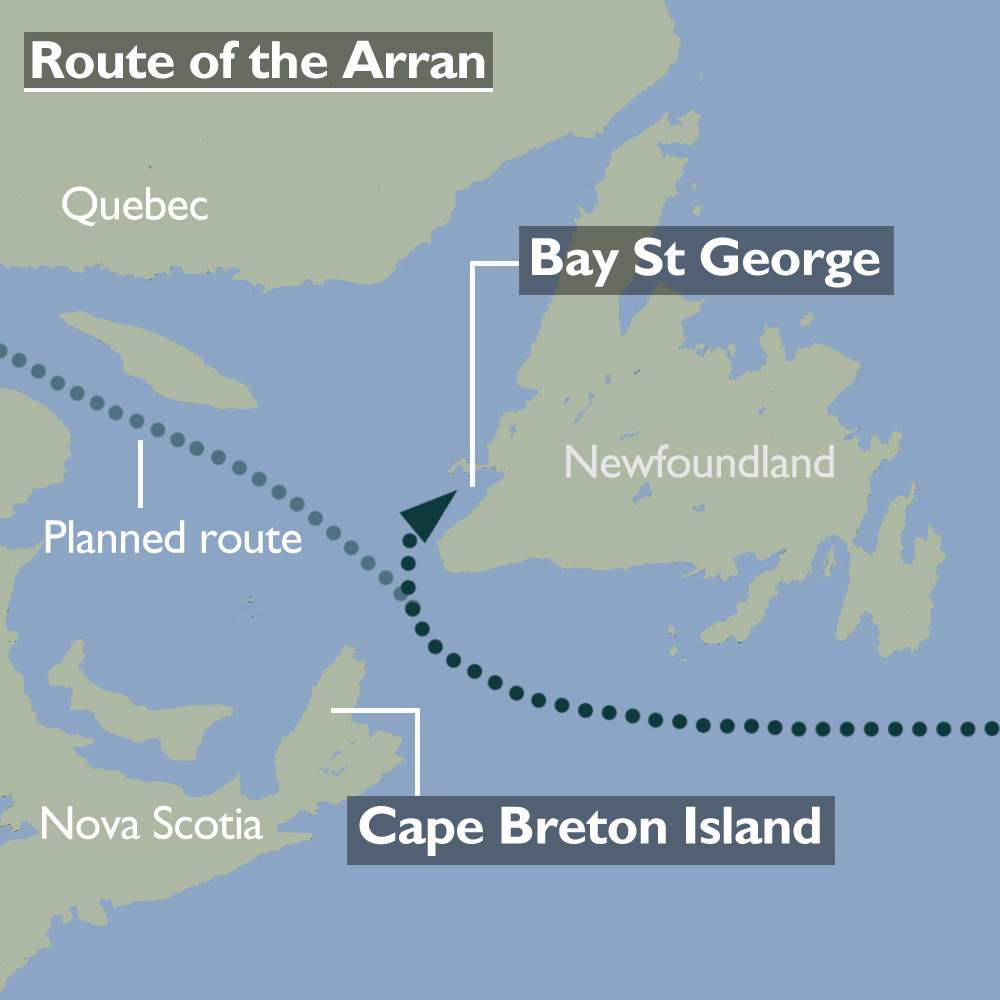

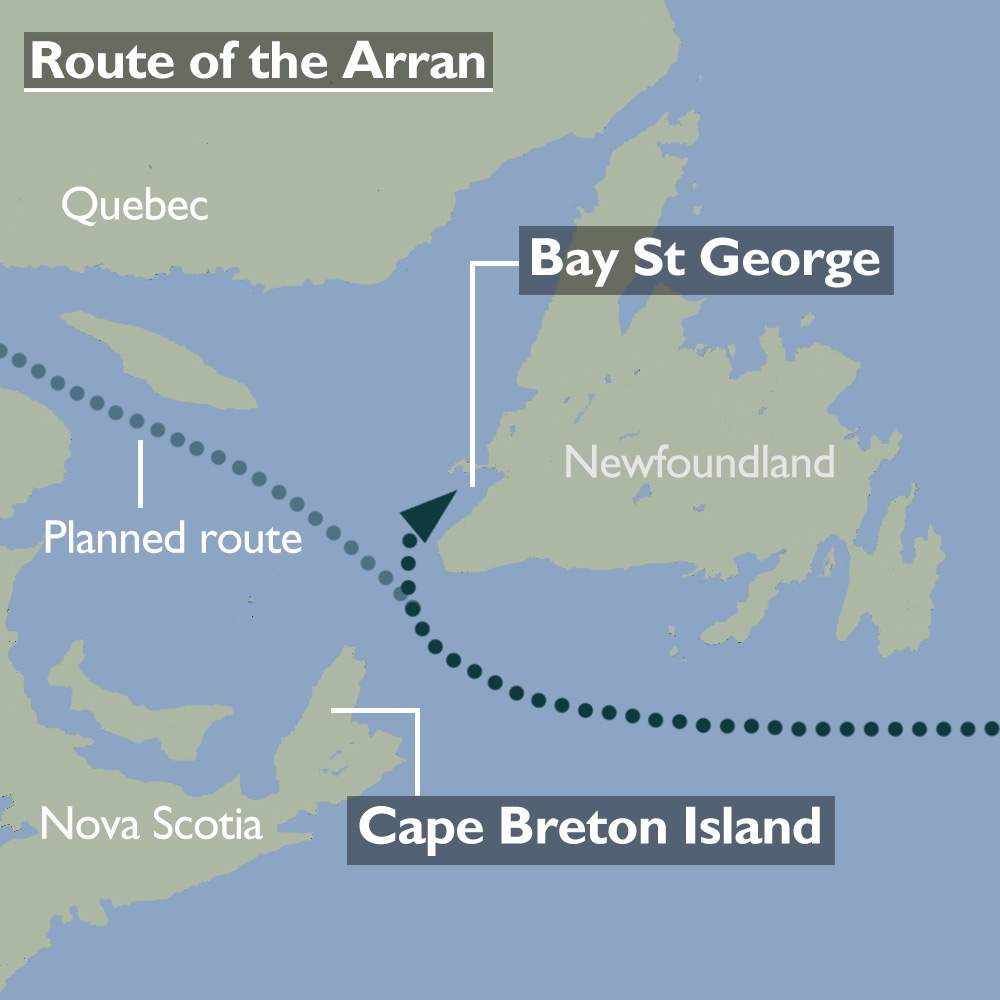

About a month after setting sail, the Arran ran into floating ice between Cape Breton Island and Newfoundland, and on 9 May the ship drifted into Bay St George, off Newfoundland's west coast, and became trapped.

With the ship going nowhere, 22-year-old Bernard Reilly - the eldest of the stowaways, who had dreams of making it to Nova Scotia to work on the railways - persuaded James Bryson that it might be worth trying to cross the ice to escape the misery on board the ship.

The younger boys were terrified of the idea, but the captain then ordered that all the stowaways except Peter Currie were to be put overboard.

“I heard the three little boys crying when they were asked to go,” seaman George Henry said in court.

“The ice was broken and rough-looking. Two of the boys were barefooted when they left the ship. The clothes of two of them were very ragged. The distance between the ship and the land, according to the best judgement I could form, was from 10 to 15 miles.

“It appeared to me rather unlikely that those without shoes would ever reach the land.”

Between eight and nine o’clock in the morning the stowaways set off across the ice. The ship’s mate threw each a biscuit as they left.

The floe was made of slabs of various sizes, some as big as a football pitch, others much smaller. Reaching the end of one, the stowaways had to jump on to the next.

Hugh McEwan, who had been poorly since leaving Greenock and had been seen spitting blood during the voyage, soon started to lag behind. He slipped into the freezing water once and was pulled free by James Bryson. When he fell in a second time he managed to crawl out himself. But each time he grew weaker.

“I saw him fall in the last time. I was in the water too,” John Paul said in court.

“He was kicking and trying to get out. He caught hold of me. I kicked and he let me go, then I got out by scrambling on the edge of the ice. I saw his head as the ice closed over it. I did not hear him cry. The ice covered over him, and I never saw him again.”

Some hours later, Hugh McGinnes sat down on the ice, his bare feet sore and swollen. He was overcome by exhaustion.

“We urged him to come along with us, and said if he did not he would be frozen,” James Bryson said.

“He said he could not come any further. We left him there with nothing to protect him - no greatcoat, nothing but his ragged, frozen clothes.”

As the remaining four stowaways neared land, the large slabs of ice became rarer. But they struggled on, each in turn slipping and falling into the water, their clothes freezing solid to their bodies.

They reached the end of the ice as the sun was going down.

They could see a few houses on the shore, but a channel of water and drift ice up to a mile wide lay between them and dry land.

Bernard Reilly, the 22-year-old, and 16-year-old David Brand tried to paddle ashore on pieces of ice, using a batten taken from the ship.

John Paul and James Bryson, frozen, famished, exhausted and weak, were stranded.

They shouted out for help in the hope that someone would hear them.

About a month after setting sail, the Arran ran into floating ice between Cape Breton Island and Newfoundland, and on 9 May the ship drifted into Bay St George off Newfoundland's west coast and became trapped.

With the ship going nowhere, 22-year-old Bernard Reilly - the eldest of the stowaways, who had dreams of making it to Nova Scotia to work on the railways - persuaded James Bryson that it might be worth trying to cross the ice to escape the misery on board the ship.

The younger boys were terrified of the idea, but the captain then ordered that all the stowaways except Peter Currie were to be put overboard.

“I heard the three little boys crying when they were asked to go,” seaman George Henry said in court.

“The ice was broken and rough-looking. Two of the boys were barefooted when they left the ship. The clothes of two of them were very ragged. The distance between the ship and the land, according to the best judgement I could form, was from 10 to 15 miles.

“It appeared to me rather unlikely that those without shoes would ever reach the land.”

Between eight and nine o’clock in the morning the stowaways set off across the ice. The ship’s mate threw each a biscuit as they left.

The floe was made of slabs of various sizes, some as big as a football pitch, others much smaller. Reaching the end of one, the stowaways had to jump on to the next.

Hugh McEwan, who had been poorly since leaving Greenock and had been seen spitting blood during the voyage, soon started to lag behind.

He slipped into the freezing water once and was pulled free by James Bryson. When he fell in a second time he managed to crawl out himself. But each time he grew weaker.

“I saw him fall in the last time. I was in the water too,” John Paul said in court.

“He was kicking and trying to get out. He caught hold of me. I kicked and he let me go, then I got out by scrambling on the edge of the ice. I saw his head as the ice closed over it. I did not hear him cry. The ice covered over him, and I never saw him again.”

Some hours later, Hugh McGinnes sat down on the ice, his bare feet sore and swollen. He was overcome by exhaustion.

“We urged him to come along with us, and said if he did not he would be frozen,” James Bryson said.

“He said he could not come any further. We left him there with nothing to protect him - no greatcoat, nothing but his ragged, frozen clothes.”

As the remaining four stowaways neared land, the large slabs of ice became rarer. But they struggled on, each in turn slipping and falling into the water, their clothes freezing solid to their bodies.

They reached the end of the ice as the sun was going down.

They could see a few houses on the shore, but a channel of water and drift ice up to a mile wide lay between them and dry land.

Bernard Reilly, the 22-year-old, and 16-year-old David Brand tried to paddle ashore on pieces of ice, using a batten taken from the ship.

John Paul and James Bryson, frozen, famished, exhausted and weak, were stranded.

They shouted out for help in the hope that someone would hear them.

The rescue

It’s May 2018 and spring has finally arrived at Highlands on the southern shore of Bay St George.

The days are getting warmer and there’s only a dusting of snow left now on the tops of the hills.

The Arran may have expected such conditions when it arrived here 150 years ago, instead of the wintry scene that awaited it.

“I have seen the sea covered in ice like that many times - it’s a combination of a cold winter and certain winds that blow ice into the bay,” says Taylor Chaffey, president of the local historical society.

“But when the boys were put over the side the ice was already decomposing with the spring temperatures so they didn’t have anything very solid to walk on - it really was a very cruel thing to do.”

Highlands was once a busy agricultural and fishing community where fishermen lived in little cabins on the beach. There is no harbour, so they fished with boats that were hauled up on a slipway.

One of those living here in 1868 was Catherine Ann MacInnis and it was she who saw the boys in the fading daylight, or heard their cries, and raised the alarm.

Her great-great-grandson, Don MacInnis, discovered this when he answered the door one sunny summer’s day about 25 years ago, and found in front of him a man from British Columbia, a descendant of one of the Arran stowaways who was searching for a member of the MacInnis family.

“Catherine Ann was my great-great-grandmother,” says Don.

“But I didn’t know anything about this horrendous story - that six boys had been thrown off a ship here and that two of them had perished on the ice. The story had been lost to our family. It was quite a shock.”

Catherine Ann’s family had emigrated to Newfoundland from Loch Morar in the Scottish Highlands in the 1850s and it is thought that her husband, Alexander, would have been among the local men who set out in a boat to rescue the boys.

“It’s not easy to see four little boys from a mile away especially at 7.30pm in the evening,” Don says.

“If they’d arrived, say, a half hour later, they probably wouldn’t have been seen at all - they were really, really fortunate to survive.”

The four frostbitten stowaways recuperated in the villagers’ homes.

Blinded by the glare of the ice, it was almost a week before they were able to see properly. It took almost a month for John Paul’s badly lacerated feet to heal.

The bodies of Hugh McGinnes and Hugh McEwan, who had perished on the drift ice, were never found.

At some point Don told the story to his old friend, Taylor Chaffey.

“Why didn’t I know something about this?” Taylor says.

“This is not something that we can allow to be lost. We need to find a way to make sure that this part of our history is saved.”

And so, like Morag Connelly in Greenock, Don and Taylor in Highlands, Newfoundland, made plans to commemorate the events that took place here.

Don designed a bronze plaque which was placed on his great-great-grandmother’s grave during a day of commemorations organised by the local historical society.

A piper led a 100-strong crowd down to the spot from where Catherine Ann is thought to have spotted the boys, and the great-grandson of the stowaway David Brand - who emigrated to Australia and established a successful engineering firm there - gave a speech, before three information kiosks telling the story of the stowaways and their rescue were unveiled.

David Brand VII and Taylor Chaffey

“What a great day,” says David Brand VII, a retired Presbyterian minister who travelled from New South Wales with his wife and son to take part in the celebrations.

“The sun shone into every heart. We are so glad we came from Australia to share in this, the memories will last forever.”

Homecoming

When the Arran eventually arrived in Quebec, one of the crew sent a letter home to Greenock describing the campaign of cruelty that the stowaways had been subjected to.

The news spread quickly around the town.

A telegraph was then sent from Scotland asking for more information and the reply came that four of the six boys who had been put down on the ice had survived - three of them were still in Newfoundland, but the fourth, Bernard Reilly, had already set off to look for work in Nova Scotia.

Almost six months after stowing away, the three remaining boys arrived back in Scotland by boat.

“One of the boys believed to be alive was named Hugh McGinnes, whose mother is a widow and resides in Nicholson Street, Greenock,” the Scotsman newspaper reported on 5 October 1868.

“The poor woman went down expecting to meet her son, when she received the painful information that he had died on the ice from exhaustion. Another lad, named [John] Paul, who was believed to have perished, has returned.”

What happened to the other survivors?

- James Bryson emigrated to the US, where he became a tram conductor

- David Brand started a ship engineering firm in Queensland, Australia, where he died in 1897

- Peter Currie, the stowaway who was not put overboard, died of tuberculosis two years after returning home

- Bernard Reilly, who went to Nova Scotia, may have never returned to Scotland

The Arran was wrecked on Sand Island in the Gulf of Mexico in 1886 while sailing from Greenock to Mobile, Alabama

The boys had arrived home just in time to appear as the main witnesses at the trial of the captain and the mate at the High Court of Justiciary in Edinburgh.

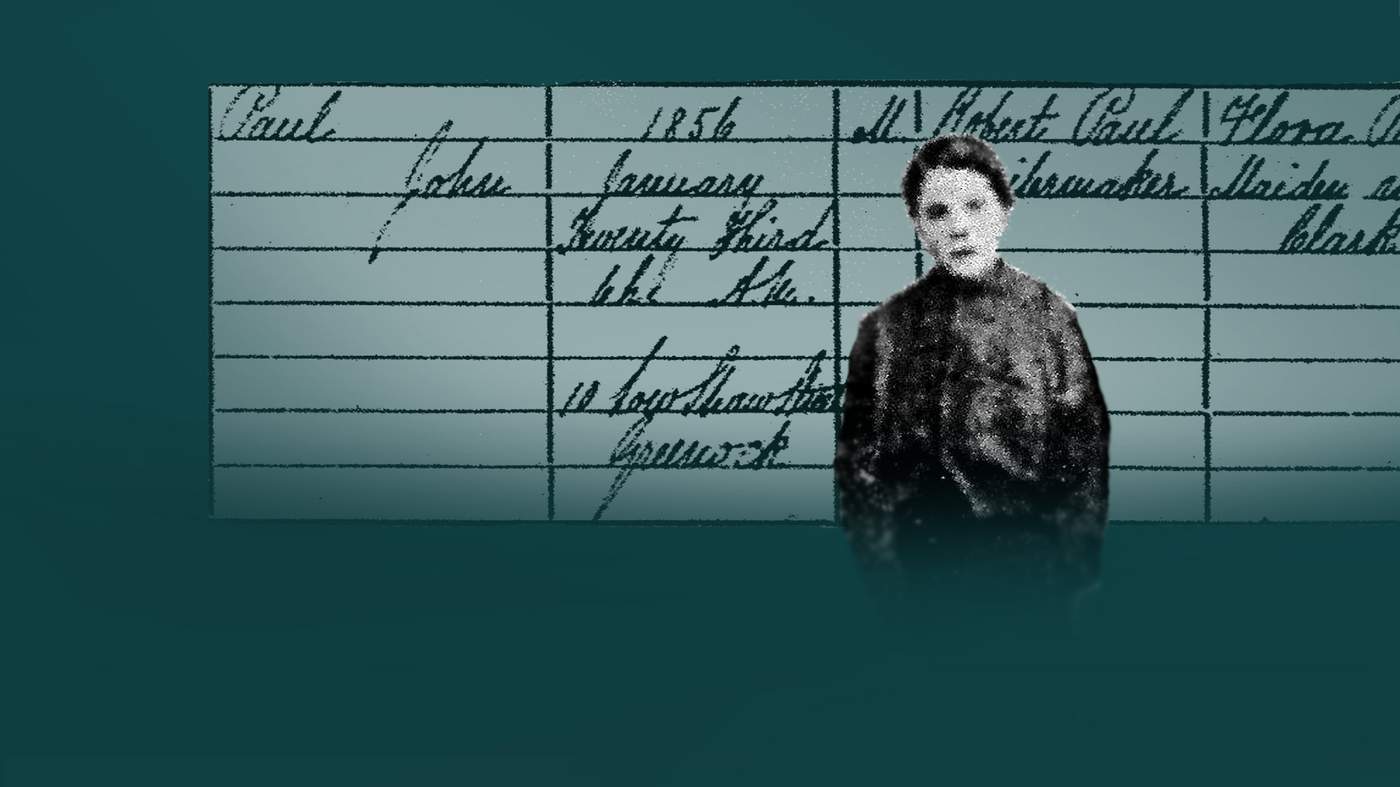

The only known picture of John Paul shows him standing between David Brand and James Bryson, three days after their return

On its final day (25 November 1868) the Scotsman newspaper reported that “the courtroom was again crowded, and many persons waited outside for several hours in the hope of gaining admission.”

James Kerr, the mate, was found guilty of assault and sentenced to four months in prison. The captain, Robert Watt, was charged with culpable homicide - roughly equivalent to the offence of manslaughter in English law - and sentenced to 18 months.

“The verdict was received by the audience with loud hisses,” said the Scotsman’s story the following morning.

Both men went back to their jobs and sailed for many years after leaving prison.

The grave

“I remember how on a winter's night my little granny would tell us John Paul's story,” says Ann McVey Haldane. “It's always been there in our family.”

Ann and Morag are second cousins - their grandfathers were brothers. But although they knew one another well years ago they haven’t seen each other for decades. Ann left Greenock 28 years ago when her husband got a new job near Basingstoke.

In making the journey south, she was in fact following in the footsteps of her great-great-grandfather, John Paul, roughly a century earlier.

Seven years after his dreadful experience at sea, the 19-year-old John Paul married and started a family. He had become a riveter, like his father before him, and rose to the rank of foreman in Greenock's shipyards. But after his wife died, in her 40s, he left for Southampton.

At a certain point, Ann McVey's parents also made the journey south, to be near their daughter.

“And when Dad came down here he started to bang on about John Paul - it reawakened something in him,” Ann says. “‘He's in Southampton,’ he'd say, ‘you need to find him.’”

It was family legend that John Paul was buried somewhere in an unmarked grave - there was an element of shame about it, Ann says, so she wanted to find him, for her father, and to put things right. “I can remember my wee granny tutting and saying, ‘Pauper's grave, unmarked,’” she says.

Ann eventually discovered that John Paul had been buried in Southampton’s St Mary Extra cemetery.

After several unsuccessful attempts, Ann found her great-great-grandfather’s plot, not far from where two large conifer trees lean in from opposite sides of the path. “Finally, there he was in his unmarked grave,” she says.

“I stood at the grave and thought about the terrible ordeal John Paul had suffered as a child. I thought about his missing fingers and toes - he lost a few due to frostbite. I thought about the child who stowed away on a ship just looking for adventure, and I said out loud, ‘You daft wee boy, what were you thinking?’”

Like her grandmother, Ann assumed that her great-great-grandfather had died a poor man since no headstone was ever placed on his grave.

So when another of John Paul’s descendants in the US uncovered a newspaper article describing a grand funeral, with a polished elm coffin covered in beautiful flowers and wreaths, and the large number of people who had assembled at the cemetery to pay their respects - including more than 100 members of the Boilermaker’s Society in full regalia - Ann was very surprised.

No-one knows why a stone was never placed on John Paul’s final resting place, but Ann and some of John Paul’s other descendants thought the 150th anniversary of his ordeal at sea was the right moment to erect a headstone.

“When you stand there in that desolate little space, it’s desperate,” Ann says. “We don’t want anything lavish, just something simple that says who John Paul was and maybe refers to the Greenock Stowaways so somebody at some point could research this history that was part of this life.”

But even though the plot has been unmarked for more than 100 years, Ann discovered that no stone can be installed without permission from the legal owner of the grave. So who was the owner?

Ann made some calls to Southampton City Council. She asked whether the owner of John Paul’s grave was the Boilermakers Society - but was told it wasn’t. “I called again and ran through all of John Paul's children as possible owners of the grave. No joy,” she says.

“Then I sat down at the computer and looked at the entries in my family tree and could see there was one more logical guess I could make. The person who purchased John Paul's grave was his second wife, Blanche Martindale Paul.”

Ann knows that Blanche outlived at least two more husbands - but has been unable to find any record of Blanche’s death or any will, so Ann cannot prove to whom, if anyone, she bequeathed her estate.

This may well ensure that John Paul’s final resting place remains unmarked forever.

“Unfortunately there are no exceptions to the rules regarding transferring burial rights. The correct procedures must be adhered to,” a spokesman from Southampton City Council said. “We are unable to consider that the grave be transferred to descendants of John Paul without following transfer procedures.”