BBC Three

BBC ThreeInside the kids-only rehab that treats video games like cocaine

What happens when you make teenagers abstain from alcohol, drugs and even Call of Duty?

I am in the most intense group therapy session I have ever sat through. It’s a ‘sharing circle’ of 20 people. Everyone except the counsellor leading the session is at least five years younger than me, and they are here because they are trying to rebuild lives that have spiralled out of control.

By sharing their worst behaviour with the group, they hope to change it.

But I am beginning to feel like I am the only one not in possession of a Sphinx-like sense of calm. One member of the group, Eva*, 19, is reading out something she’s written. It’s a list of all the ways her behaviour has hurt the people she loves the most.

“One: a few months ago I told my parents I don't love them,” she says in a deadpan voice. “I hurt them a lot by saying that.

“Two: last year I screamed to my boyfriend that I wanted to kill myself…”

The list goes on and on. Eva recites many things she seems to think she has done wrong: not showing her feelings, being a perfectionist, lacking self-discipline. She doesn’t brush her teeth. She doesn’t play sports. Sometimes she doesn’t shower.

I am struck by Eva’s honesty and, by the end of her reading, I’m starting to feel quite sorry for her.

Kyra, the counsellor leading the session, addresses the circle.

“Who has some feedback? Let’s see some hands,” she says. “Ethan*.”

Ethan, a 17-year-old in skinny jeans, turns to Eva. I wonder if he is about to offer some words of support.

“I’m tempted to just say something obvious like, 'Good share', or whatever,” says Ethan, brushing his hair across his face. “But what were the consequences of your perfectionism? It's a bad thing if you take it to the extreme, but did you really do that? Did it make your life unmanageable?”

“I think so,” replies Eva, cautiously. Her feet are crossed underneath her chair, and she is looking from person to person. Twenty pairs of eyes silently return her gaze.

Kyra looks around, her eyes narrowed. “What feeling do you all think that’s based on?” she asks the room.

There is a pause. Then another teenager, Thomas*, breaks the silence.

“I think your perfectionism is related to being a victim. You don’t realise that you’ve made mistakes, so instead you play the victim role.”

My palms are pressed under my legs, and I notice that they are hot. My phone vibrates noisily. It occurs to me that I haven’t checked it in an hour, and I have to consciously suppress an urge to grab it. I am anxiously holding my breath as I look at Eva.

Eva’s mouth is moving. In the silence, it is possible to hear her making faint pop-pop noises, as if she is about to speak. At first I think she is upset. I sit on my hands and watch, wondering if she is about to cry. My phone buzzes again. I remove it from my pocket without thinking and instantly replace it.

But Eva does not cry. She does not say anything at all. The room watches her silently. I begin to suspect that she is not upset at all: she is actually furious.

Kyra turns back to the group.

“Who here feels self-pity?” she says.

The room erupts into a chorus of ‘sure’ and ‘absolutely’.

“Do you want to change?” Kyra asks Eva.

“Yes, I want to change,” says Eva, a hint of indignation in her voice.

“Are you aware that your behaviour was all about getting attention?” Kyra says to Eva.

There is a pause.

“Not yet,” Eva says quietly. “But I’m going to learn.”

BBC Three / Tomasz Frymorgen

BBC Three / Tomasz FrymorgenTwo hours earlier, I had just arrived at Yes We Can: a mental health facility located down a long, tree-lined boulevard in a quiet corner in the south of the Netherlands. As my taxi approached its imposing black gates, the trees framed a large estate with sprawling, well-manicured grounds. This pristine, cuboid mansion could have been made out of pixelated blocks in Minecraft; or provided the setting for a level of Hitman – the long-running game series in which you play an assassin who ruins glamorous parties by garrotting the waiting staff and dropping a chandelier on the host.

There is a reason video games are on my mind. This clinic is for those aged 13-25 only, and people come from all over the world for its specialist treatment in mental health problems including screen addiction and other behavioural issues that the medical community is unsure of how to classify – let alone treat. Many of the people attending say they are addicted to their smartphones, social media, or video games.

For the first time this year, the World Health Organisation has accepted that they might be right. In June, it formally accepted Gaming Disorder into the International Classification of Diseases (ICD) – a kind of encyclopedia of stuff that can go wrong in humans. The treatment programme at this clinic arguably goes further: it places video games on an equal footing with drugs, alcohol, and gambling, demanding that those who complete its 10-week programme abstain from all of them for the rest of their lives.

Debate over whether smartphones and video games are addictive has raged for almost as long as they have been around. I wanted to see if the people behind this clinic were on to something – or if they ran the risk of framing normal teenage behaviour as harmful.

BBC Three / Tomasz Frymorgen

BBC Three / Tomasz FrymorgenIt’s a subject that founder Jan Willem Poot, 42, feels strongly about. He bounds into my line of sight tapping away on his phone, which he places in a pocket before shaking my hand enthusiastically. He founded the clinic in 2010 to fill what he perceived as a gap in the market for a Dutch mental health facility that offered personalised treatment to young people.

“I was inspired by Barack Obama’s campaign slogan,” he says, smiling.

Jan Willem is a ball of enthusiasm, with piercing blue eyes, a good suit, and glowing skin. He makes regular television and media appearances in the Netherlands. It’s a sharp contrast, I think, to how his life must have been during his teenage years, when he was taking up to eight grams of cocaine every single day. Clean from drugs and alcohol since 2004, Jan Willem founded the clinic to help young people overcome their mental health problems, far away from the reminders of their addictions and behaviours.

So it came as some surprise to Jan Willem when the first young people to arrive at his clinic often said they were hooked on Call of Duty – not cocaine. And for these gaming addicts, the grounds of the Dutch mansion were triggering in a way he had never anticipated.

“Every week we’d go on a hike in the woods,” says Jan Willem, wide-eyed. “And we had multiple kids saying, ‘This looks exactly like I'm in a game of World of Warcraft' – or Battlefield, or whatever.

“They were imagining that, behind every tree or rock, an enemy was lurking, or that behind every hill a whole army was coming."

Jan Willem may not have understood video games, but he had a pretty good grasp of how addiction could warp your world. Physical and emotional abuse had helped nudge him towards drugs and alcohol as a 12-year-old, he says. From the age of 18 to 27, he tried countless treatment approaches. There were four years in rehab, a revolving cast of around 30 psychologists and psychiatrists, multiple diagnoses – ADHD, depression, a form of autism – and numerous relapses.

“I hated psychologists. I hated psychiatrists,” he says. “Everybody who came too close to me, I would push them away.”

He finally kicked the habit at Castle Craig: a mental-health and addiction facility set in a Scottish country house. Jan Willem paid for his treatment with a health insurance plan (mandatory for all Dutch nationals) he’d taken out years earlier. The experience was completely unlike anything he had been through before.

"For six months it was love, warmth, and counsellors who were the biggest pain in the ass ever," he says. "But that [confrontation] was what I so desperately needed."

At 27, Jan Willem was finally clean – and suddenly had his whole life ahead of him.

So he threw himself into business. He started an outdoor activity company for teenagers. Within three or four years he was taking more than 10,000 teenagers hiking in the woods.

But he never forgot his struggles with addiction, and five years into his recovery he decided to to open a mental health clinic in his home country.

Yes We Can started as a facility for 120 Dutch nationals, whose places are paid for by a mix of insurance companies and local government (the Netherlands has a healthcare system that is entirely state-funded for under-18s, with a means-tested contribution for uninsured low-earning adults). In August 2017, they welcomed 24 fee-paying internationals for the first time – and the UK has become their biggest global customer.

Jan Willem had a clear vision for his clinic. It would treat young people using everything he had learned – with a few important differences. It would be a space for young people only, and it would treat mental health issues in whatever form they arrived. The clients would be 'fellows' – not patients – and they would have to stick to a strict schedule, which included at least two hours of exercise, lots of group activities, and two sharing meetings a day. The point of it was to foster 'connection' between young people, who may – like Eva – have alienated themselves from their friends and family, or had no social skills whatsoever.

The clinic takes the view that addiction is a disease, and that addicts will often swap one addiction for another – meaning they have to give up all other addictive substances for good. Other 12-step programmes such as Alcoholics Anonymous consider this to mean drugs and alcohol – but here the definition has been expanded to include gaming. Upon completion of the programme, screen use – laptops, phones, and social media – is permitted, but has to be monitored.

Stefan handles communications for the international wing, which houses young people from more than 15 different countries. He greets me outside the front door.

The NHS does not provide funding for young people from the UK, so the ten-week residential programme costs £50,000. It sounds like quite a lot of money, I say.

“Yes, it can be very hard on the parents,” says Stefan. “Some of them have discussed selling their second homes.”

BBC Three / Tomasz Frymorgen

BBC Three / Tomasz FrymorgenThe clinic claims that more than 70% of young adults that complete its programme don’t need any specialised mental healthcare after treatment – a success rate that counsellor Kyra puts down to its confrontational methods.

“The kids learn the most from them themselves. They're each other's best critics,” says Kyra.

I ask Kyra about the confrontation that took place with Eva where she was told that she was playing the victim.

“Usually the first two weeks we just let them settle in,” she says. “But Eva had a lot of therapy before she came here.”

So she knows what to say to paint herself in the best possible light? I ask.

“She knows exactly what to say," Kyra says. "In her case, we confronted her with it soon. But usually, the confrontation starts around the end of week three.”

So do you break them down to build them up again, I ask?

“Well, I wouldn't say break them down, but I would say confront them with their own behaviour. Most kids, when they come in, think, ‘I don't need to be here because I'm not as sick as everyone else is’.”

The approach might sound tough – but Kyra says it works because the kids share many problems. For instance, “95%” have fairly low self-esteem, she says; almost all of them find it difficult to voice their emotions; most of them feel that they haven’t been heard; and most of them feel they don’t belong.

BBC Three

BBC ThreeIn the woods, the kids have begun their first group activity of the day: a treetop assault course. Thomas, who earlier called Eva out for being a victim, is not exactly enjoying it.

“It’s so wobbly!”

It is the day before Thomas’s 20th birthday. He is strapped into a safety harness and suspended halfway up a ladder in a forest.

“I can’t do it! I hate heights.”

Thomas starts choking back tears. He is approximately 20 feet off the ground, two steps from the treetop platform. It’s the furthest he’s ever been – but it’s not as far as he wants to go.

“You can do it Thomas!” shouts James, from London, who is here to address issues including drug use, partying, and violence. James is tackling the course in reverse. To up the challenge, he has also been blindfolded. I watch as he arches his leg like a pony, stretching for the swaying platforms in front of him.

Eva, who started the course a little earlier than Thomas, is ignoring the wooden platforms and making her way through the course using the guide ropes that connect them.

Thomas climbs back down the ladder and rubs his face. I walk over to him. At more than six feet tall, he towers over me. He's breathing heavily, his cheeks pink. I ask him why he has come here.

“Primarily a gaming addiction,” he says, fiddling with his climbing harness. “But also an eating disorder and perhaps an addiction to porno too. Well, that’s still up for debate.”

Thomas is in his sixth week at the clinic. He was first in contact with the team two years ago – but he decided he didn’t want to go into treatment.

“I was like, 'I'm not going to sit between a bunch of alcoholics and drug addicts just because I like video games',” he says.

But when Thomas couldn’t get his gaming under control, his opinion changed. He decided to try it. So far, Thomas has been pretty happy with his progress – but he found deleting his gaming accounts hard.

“I was sweating and crying,” he says. “Even though it was a problem, I still have good memories of playing games and meeting people on there.”

Over the last six weeks, Thomas has learnt to enjoy being outdoors – something he rarely experienced when he was gaming for 16 hours a day.

He has mountain biked through caves, hiked in the woods, and braved his fear of heights at an indoor climbing wall. And he was particularly taken with a wild bird show.

“I fully expected that to be kind of lame,” he says. “But it was so much fun. They pulled out a bald eagle! It was beautiful.”

I am impressed by Thomas, who seems thoughtful, self-aware, strong and vulnerable. At an age when many other 19-year-olds are in their first few years away from home, drinking and partying to excess, he is imagining a very different future to the one he was facing even a year ago.

“I know that even if I'm completely happy in my life, I can't start drinking alcohol,” he says. “That's a thing here. If you're addicted to gaming, you’re not allowed to ever drink again either.”

Still, Thomas seems to be enjoying himself. Half an hour later, the kids are in a makeshift karaoke booth that they have built out of wooden beams, rope and a tarpaulin. I marvel as Thomas grabs the mic and performs a word-perfect rendition of Rap God by Eminem: a six-minute, 1,500-word rap that features some of the rapper’s fastest verses.

The other kids cheer him all the way through.

BBC Three / Tomasz Frymorgen

BBC Three / Tomasz FrymorgenThere is something about watching the karaoke that I find strange for reasons I don’t immediately understand. Then I realise it’s obvious: this is a group of teenagers and twenty-somethings who are completely sober, singing in a tent in broad daylight. In this moment, they seem younger than their age – and I almost forget that they’re all dealing with their own issues.

As young people from wealthy families able to afford private treatment, the international fellows are in some ways fortunate. People from disadvantaged backgrounds face a higher risk of mental health problems, and far fewer treatment options. While the Dutch government funds treatment at the clinic for people from all backgrounds, the NHS does not have an arrangement in place with Yes We Can. The clinic's £50,000 price tag puts it on a par with some of the UK’s upmarket residential rehabilitation facilities, like celeb favourite The Priory, placing it well out of the reach of all but the wealthiest.

And there is mounting evidence that young people of all backgrounds in the West are facing a crisis in mental health. In recent years there has been a sharp increase in anxiety disorders and depression. Statistics released this week by NHS England show that nearly one in four young women have a mental illness, with emotional problems such as depression and anxiety the most common. The number of referrals to child and adolescent mental health services in England has increased by 26% over the past five years, Education Policy Institute research suggests.

Professor Jean Twenge suspects there may be a common denominator. In her book iGen the psychology professor argues that teen behaviours and emotional states underwent a dramatic change after 2012. That year, she wrote, also happened to be exactly the moment when the proportion of Americans who owned a smartphone surpassed 50 per cent.

Young people are “on the brink of the worst mental health crisis in decades,” she wrote, “[and] much of this deterioration can be traced to their phones.”

Prof Twenge found a correlation between the rise in smartphone use and a rise in depression and loneliness among young people. She also said that after 2007 – the year the iPhone was released – young Americans experienced a fall in socialising, a fall in dating, and even less sex.

Teenagers have more free time than ever before, she wrote. “So what are they doing with all that time? They are on their phone, in their room, alone and often distressed.”

I wanted to know how Prof Twenge could be so sure that smartphone use really was the cause of higher rates of depression in young people, so I emailed her.

She pointed me to two recent studies into social media use. The studies compared the wellbeing of participants who took a break from social media – or severely limited their use of it – to the well-being of those who didn’t. They found that the people who ditched social media for a while felt happier (or at least a little less sad).

"Twice as many high users of devices [like phones] versus low users are unhappy, depressed, or anxious," she says.

Not everyone agrees, however. Dr Pete Etchells, a reader in psychology at Bath Spa University, argues that Prof Twenge’s work shows a link between smartphones and depression – but not that one causes the other. He warns that we run the risk of medicalising behaviours that are not recognised mental health issues, such as screen addiction and social media addiction, and over-diagnosing ones that are – such as gaming addiction.

“We attach the word ‘addiction’ to something that looks like harmful use when really we don't have a good handle on what that actually is,” he says.

Research into screen addiction, social media addiction, and gaming disorder is still in its infancy.

“You can easily see how obsessively using cocaine or heroin could cause you harm,” he says. “But the research into gaming addiction doesn't do a good job of distinguishing between people who are highly engaged in playing them, but don't suffer any problems as a result, and people who do.

“But nobody is saying that there is not a certain group of people for whom playing video games is problematic."

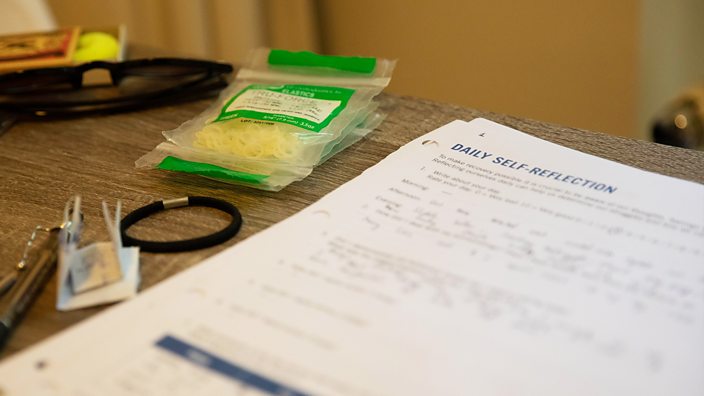

BBC Three / Tomasz Frymorgen

BBC Three / Tomasz FrymorgenI wonder if Dr Etchells is right. Perhaps there is a risk of over-diagnosis. By the time I am halfway through my visit, I have met a lot of young people with a range of serious problems. Are they 'sick enough'? What does 'sick enough' look like, anyway?

And then I sit down to interview Ethan, the 17-year-old from London in the skinny jeans. Ethan has been at the clinic for almost 10 weeks. He is friendly and charismatic – totally different, he says, to the person he was when he arrived.

“I was terrified of everyone,” he says.

Ethan talks to me with the unflinching honesty characteristic of everyone I meet there. He takes me through his daytime routine before joining.

“I would wake up at maybe six in the afternoon,” he says. “I used to stay awake during the night. It's more comfortable. Less people around. When my parents were sleeping I’d go downstairs, grab something to eat.”

What would happen if you met your parents? I ask.

“Very simple,” he says. “I’d just ignore them.”

I can feel my phone vibrating again. It feels like a flurry of WhatsApp messages. For a moment I am totally distracted. I consciously refocus my attention on Ethan.

Ethan spent a lot of time crying in his room. He had panic attacks. He would self-harm. He used drugs – “anything that I could get my hands on” – and played video games through the night. At 15, he dropped out of school.

“I thought I was screwed for life,” he says.

Ethan’s behaviour didn’t even make sense to him at first. His parents were loving, he says, but they didn’t know what to do with him. Then it emerged that Ethan had been keeping something from everyone: he’d experienced serious childhood trauma.

“I just kept that in and told myself it was fine,” he says. “I avoided it because I couldn't face it.”

When Ethan checked in for treatment, he found he was finally able to talk about his experience and connect with people his own age.

“For me, what worked was the fact that they could observe my behaviour all the time," he says. "Instead, of just coming in once a week [to see a therapist], preparing for that and then bullshitting my way through.

“I can't bullshit my way through here,” he says.

BBC Three / Tomasz Frymorgen

BBC Three / Tomasz FrymorgenThe interview is over. Ethan leaves the room. It occurs to me that although the people I have met have been exceptionally open about their behaviour, until my encounter with Ethan I did not know much about their backgrounds at all. The clinic's UK fellows are privileged in some ways – but no amount of wealth can mollify childhood trauma, which is a significant risk factor for substance use and mental illness.

Jan Willem returns to the room with his phone in hand, prodding at it with his thumbs. I check my own phone and feel a mix of disappointment and shame when I see a blank screen staring blankly back at me. I had imagined the vibrations. I am a deluded millennial with no friends.

Do you get a little rush of pleasure when you receive a notification? I ask. Jan Willem smiles.

“Yes I do! Absolutely,” he says.

But do you see that as a sign of addiction? How do you protect kids from that? I ask.

“We sometimes suggest that the kids disconnect from social media,” says Jan Willem. “But we never advise a total abstinence from it.”

“Because out there – in the world – they will need their phones and laptops. I've got a Facebook account and I've got a LinkedIn account which I’m using mostly for my business. And I'm an addict. But I have to use them as well.”

I cradle my own phone in my palm, which is recording our conversation. The screen lights up. A notification. I am conscious of an overwhelming urge to check it.

Does that make me an addict? Am I hooked on WhatsApp? If I didn’t go to work could I spend several hours sending selfies on Snapchat? And could I transfer that to gaming, alcohol, drugs?

I look to Jan Willem and try to imagine a life in which I am consuming eight grams of cocaine a day.

Better to stick to Instagram, I think, pocketing my phone.

*Some names have been changed

If you have been affected by issues raised in this article support is available.