400th Anniversary of the Mayflower

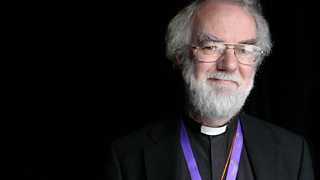

Radio 4's Sunday morning service with the Right Reverend Nick McKinnel, Bishop of Plymouth.

Four hundred years ago this week, a small ship set sail from Plymouth to the New World. Its passengers were in search of a better life. Some were seeking religious freedom, others a fresh start in a different land. The Right Reverend Nick McKinnel, Bishop of Plymouth, reflects on the story of the Mayflower and the significance of this voyage for today's world.

Producer: Dan Tierney.

Readings:

Exodus 14: 21-22; 26-30

Hebrews 11: 13-16 and 12:1-2

Introit:

They that in Ships unto the Sea down go (Psalm 107), from “They that in Ships unto the Sea down go: Music For the Mayflower” (Resonus), performed by Passamezzo

Hymns:

Guide Me O Thou Great Redeemer (Cwm Rhondda)

Eternal Father, Strong to Save (Melita)

Who Would True Valour See (Monk’s Gate)

(sung by St Martin's Voices, directed by Andrew Earis)

Anthems:

Never Weather Beaten Sail (Thomas Campion) from “They that in Ships unto the Sea down go: Music For the Mayflower” (Resonus), performed by Passamezzo

O Sing unto the Lord a New Song (Thomas Tomkins), performed by The Tallis Scholars

Drop, Drop Slow Tears (Orlando Gibbons), performed by Voces8

Instrumental music:

The Inconstancy of the World (Anonymous)

Love's Constancy - Corydon's Resolution (Thomas Ford)

The Bird’s Dance (Anonymous)

(from “They that in Ships unto the Sea down go: Music For the Mayflower” (Resonus), performed by Passamezzo)

Last on

More episodes

Previous

Sunday Worship-400th Anniversary of the Mayflower

INTRODUCTION

BISHOP NICK: I’m standing at the entrance to Sutton Harbour in Plymouth by the Mayflower Steps. They have been smartened up by the City Council for this anniversary, flags are flying, the railings gleaming, because it was from near here four hundred years ago this week that a small ship, not much larger than a modern double-decker bus, set sail from Plymouth into the Western Approaches. On board were 102 passengers and around 30 crew. Today, more than 30 million people can trace their ancestry to them.Nine and a half perilous weeks later, after a stormy crossing, the Mayflower arrived off Cape Cod. Shortly afterwards they found a place to settle across the bay in a little harbour already by chance called Plymouth.

Many of those travellers are better called Separatists than Puritans. They wanted to be ruled not by bishops or the state but to look to the scriptures for their faith and inspiration, embracing the spirit of the reformers and holding the courage of their own convictions. Persecution by the established church had bred in them a deep concern for liberty of conscience and freedom of thought and worship.

The rest is history – or at least history laced with generous doses of mythology, for this was not the first English colony in North America; within six months nearly half of the settlers had died; and they were largely saved by local Native Americans who spoke English and were able to instruct them in the art of survival. Ultimately, the growth of the colonies came at a cost to the indigenous people. But within a few generations the story of the Mayflower Pilgrims had come to encapsulate the vision and origins of the United States of America. Four hundred years ago it may have been, but it resonates with our world today. There are still those undertaking perilous journeys across the sea in search of a new life; still those in parts of the world who face persecution and even death because of their faith in Christ and their determination to serve him. And recent protests on both sides of the Atlantic have shown that this is a moment seek greater understanding about our colonial past.

OPENING PRAYER

A Prayer: Gracious God, our heavenly Father, as we remember this morning those who ventured across the seas in search of new freedoms, grant us the courage and vision to hear your call in our day. Open our eyes to the truth that sets us free, and open our hearts to the cry and suffering of so many in our world as we look to that day when we can rejoice in the peace and justice of your Kingdom, through Jesus Christ, our Lord, Amen.

HYMN –Guide me O Thou Great Redeemer

BISHOP NICK: Those aboard the Mayflower were conscious that they walked in a great tradition of pilgrims. We can hear now from Stephen Tomkins, the author of “The Journey to the Mayflower: God’s Outlaws and the Invention of Freedom”.

STEPHEN TOMKINS: It’s often said that the Mayflower pilgrims sailed to North America to escape religious persecution. It’s true that many members of their Separatist movement had suffered imprisonment and death in England for their faith. But after three of their leaders were executed in 1593, the Separatists took refuge in Leiden in the Netherlands, and there they enjoyed freedom of religion for 27 years before the Mayflower sailed. So, if they no longer needed to escape persecution, why did they take the dreadfully dangerous course of migrating to North America? They went because of a Bible story.Then Moses stretched out his hand over the sea. The Lord drove the sea back by a strong east wind all night, and turned the sea into dry land; and the waters were divided. The Israelites went into the sea on dry ground, the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left.

STEPHEN TOMKINS: In the book of Exodus, God’s people, the children of Israel, are slaves in Egypt. It’s the land of their birth, but a godless place of oppression, where they are subjected to cruelty and violence, by an unholy regime. So, in the story of the Exodus, God leads the Israelites out of Egypt, across the sea, to the promised land, where they will be free and prosper.

Then the Lord said to Moses, “Stretch out your hand over the sea, so that the water may come back upon the Egyptians, upon their chariots and chariot drivers.” So Moses stretched out his hand over the sea, and at dawn the sea returned to its normal depth. As the Egyptians fled before it, the Lord tossed the Egyptians into the sea. The waters returned and covered the chariots and the chariot drivers, the entire army of Pharaoh that had followed them into the sea; not one of them remained. But the Israelites walked on dry ground through the sea, the waters forming a wall for them on their right and on their left. Thus the Lord saved Israel that day from the Egyptians.

The Separatists believed that they were the people of God in their own day, just as the Israelites were in the Bible. They were suffering in the same way – England was the new Egypt. And so they believed that God was leading out of that land of chains and blood, across the sea to freedom, in the Netherlands.

The problem was that the Netherlands did not turn out to be much of a promised land. They enjoyed religious freedom there, but they lived in poverty, they suffered splits and scandals, life was hard, their numbers declined. What did these struggles mean? They looked again at the story of the Exodus and remembered that after God led Israel out of Egypt they had wandered for many years in the wilderness – a time of testing – before the Lord led them again, through the waters of the Jordan, finally, into the promised land.

So the Separatists concluded that, following the same pattern, they too had another journey to make before they reached the place to which God was calling them. After the Separatists settled in New England, many other Puritans followed. And many of them were determined to establish a new, improved version of the all-encompassing state church of England, enforced on all citizens. The Separatists, however, remained true to their vision. Their church in America, as it had been in England, was a voluntary community, a gathering for those who chose to worship together, a place of freedom. It was also one episode in what became a vast colonial enterprise that was not always about freedom and non-violence – indeed far from it. Nevertheless, those of us who value the freedom of religion and thought that exists today – and see it being denied to people in various parts of the world - have good reason to look back with gratitude to those dissidents who paid a steep price for it 400 years ago – and continue to do so – whether by facing prison and death at home, or by embracing the life of exiles.

MUSIC – Never Weather Beaten Sail (Thomas Campion)

READING - Hebrews 11: 13-16 and 12: 1-2A reading from the letter to the Hebrews. All of these died in faith without having received the promises, but from a distance they saw and greeted them. They confessed that they were strangers and foreigners on the earth, for people who speak in this way make it clear that they are seeking a homeland. If they had been thinking of the land that they had left behind, they would have had opportunity to return. But as it is, they desire a better country, that is, a heavenly one. Therefore God is not ashamed to be called their God; indeed, he has prepared a city for them.

Therefore, since we are surrounded by so great a cloud of witnesses, let us also lay aside every weight and the sin that clings so closely, and let us run with perseverance the race that is set before us, looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of our faith, who for the sake of the joy that was set before him endured the cross, disregarding its shame, and has taken his seat at the right hand of the throne of God.

HYMN – Eternal Father, Strong to SaveREFLECTION

BISHOP NICK: A few years ago I made a visit to Calais with a charity called Safe Passage which works to help those legally entitled to live in the UK. It was soon after the Jungle had been demolished and I vividly recall the extraordinary number of people of all ages emerging from woodland onto a desolate industrial estate around lunchtime.

Through desperation or aspiration they had risked their lives in little boats or hidden in trucks, crossing continents in a bid to find security and hope. Whatever the politics, it was difficult not to be moved by their plight, and by the compassionate humanity of the volunteers from across Europe who were providing food and tents.What is it like to leave everything behind to begin again in a foreign land? Liliane Uwimana now reflects on her own family’s journey to a new life here in Britain.

LILIANE UWIMANA: I am a mother of 4 children’s, 2 boys and 2 girls. My journey started in 2005 coming from Rwanda to UK to join up with my husband. Because of the genocide that happened in Rwanda, we had to leave and find a refuge here. We were granted a family reunion after waiting for almost 5 years. My boys were 7 and 5years old then. Coming to the UK with no language and young children who have not seen the father for a long time was hard.The second part of my journey was adapting to the cultural, language and weather. It has been so hard to find my feet in England. After learning a language from scratch, I have managed to finish University in business management, supporting my husband to start and grow his business here in Plymouth. I have been blessed to sit on the board of trustees for a school where I first learned English. In all the ups and downs, I have seen my faith in God making its way in our lives and doing wonders that only he can do. I am a strong believer of the verse in Jeremiah which says: ““I know the plan I have for you”, declares the Lord, plans to prosper you and not to harm you, plans to give you hope and a future.”

BISHOP NICK: That was Liliane Uwimana. The historian Tom Holland writes that “Christianity has two deeply subversive ideas at its heart: that all people are equal and that the weak are heroic”. Those ideas flow from the ministry of Jesus walking the roads of Galilee teaching, healing, praying until the powers of his day denied his “freedom of religion” as on the cross he laid down his life for his friends, making possible the forgiveness and grace that we can know today.

In response to that grace and alongside their vision of a new land, the Pilgrims determined to live out the values of their faith with the creation of a fairer society. While still aboard the ship they drew up the Mayflower Compact to form what they called their “civic body politic”, the arrangements for the sort of community they would become. It fits on a side of A4 and is perhaps their most significant legacy, setting in train an approach which came to influence the American Declaration of Independence and the UN Declaration of Human Rights.

The author Kate Caffrey describes their achievement in these words: “The system of laws and management set up by the Pilgrims may not seem startlingly democratic today, but it was a great advance on anything seen before then. They made a plantation, and kept it going despite death, disease, terror, storm and tempest on the spot, exploitation and swindling from within and without. They dealt fairly with one another and with all they met. Steadfast endurance in trials, inspiring leadership, dauntless faith sustained them. They created one of the best-ordered and most successful colonies ever known”.

They were conscious of those who had gone before, the people of Israel journeying to Canaan, the strangers and pilgrims desiring a homeland and in the words of the Epistle to the Hebrews “looking to Jesus the pioneer and perfecter of their faith” who had prepared “a better country, that is a heavenly one”. The Christian journey still requires courage of heart, independence of mind and piety of spirit and those who embark upon it can still draw inspiration from those who set out from these shores four hundred years ago to become the founders of a mighty nation.

MUSIC - O sing unto the Lord a new song (Thomas Tomkins)

BISHOP NICK: Despite the noble ideals of the separatists, the legacy of the Mayflower makes us confront an uncomfortable truth – that the freedom and aspirations of one group of people can come at a cost to another. The story of the Mayflower lays bare the complexity of human experience. Many colonisers inflicted death and destruction on the indigenous peoples, taking land, bringing further disease and betraying the trust of those who had offered hospitality to the first arrivals. Their story is one also to be told - by Dr Kathryn Gray, Associate Professor in Early American Literature at the University of Plymouth.

KATHRYN GRAY: When the Mayflower passengers set sail for North America in 1620, they took a patent, a legal document, which gave them authority to settle a parcel of land in North America. These political arrangements took no account of the Indigenous people already living in the region.

By 1620, Indigenous coastal communities were aware of European arrivals and interventions: the Dutch were developing trade in the region; and printed accounts of Indigenous men taken captive from the shoreline and forcibly removed to Europe, were circulating in the early decades of the 17th century. For the Wampanoag, the tribe closest to the colonists, geographically and, later, diplomatically, the impact of European disease was beginning to take its toll. The place called Patuxet, a village devastated by disease just a few years before the Mayflower arrived, became the chosen site of the Plymouth Colony. William Bradford, an early Governor of the colony, commented years later that ‘God cleared a space for us in the wilderness.’ This clearing came at a human cost; the providential errand had visible and unrelenting consequences for Indigenous people.

The first settlers of the Plymouth colony relied on the Wampanoag for food, in the first instance; for translation, as they integrated in the region, economically and diplomatically; and for protection, through a Peace Treaty that, at least ostensibly, agreed to mutual protection. The arrival of many more settlers, and the emergence of many more colonial settlements in the New England area in the decades that followed, meant that relatively local conflicts, tensions and violence caused by settlement at Plymouth, soon developed into a crisis across the region. Conflicts called the Pequot War, of the 1630s, and King Philip’s War, of the 1670s, had devastating impacts on Indigenous people.

The arrival of the Mayflower in North America 400 years ago is a point of connection, not necessarily beginning. It connects the religious experiences of the Separatists in England and Leiden, with England’s colonial ambitions in North America, and all of this connects with centuries of Indigenous history and culture that western traditions are only just beginning to understand. Over the centuries, the voices and perspectives of the colonists have dominated the ways in which this past constructs a narrative of national origins. At this moment of reflection, 400 hundred years later, and thanks to the work of numerous Indigenous leaders, scholars, artists and curators, the significance of this point of connection is productively and permanently transformed, revealing the deep and complex entanglements of our shared histories.

MUSIC - Drop, Drop, Slow Tears (Orlando Gibbons)PRAYERS

BISHOP NICK: In our prayers we bring before God the needs of our troubled and complicated world.

For those who bear the privilege and responsibility of government, we pray for wisdom and compassion, that in a world where so many are migrants and refugees, the nations of the world may work constructively for the good of all. Lord, in your mercy, hear our prayerWe pray for those who at this moment are risking their lives to escape violence, hunger or persecution, that they may find the peace and security they crave. Lord, in your mercy, hear our prayer.

We think of those whose freedom of worship is curtailed by the authorities, and those who are persecuted or imprisoned for their faith, asking that they may be given courage and strength to uphold them in their time of need. Lord, in your mercy, hear our prayer.And for those of us with comfortable lives and secure homes, grant us your Holy Spirit that we may have a better understanding of the predicament of others, and give us that kindness of heart and generosity of spirit that seeing need, we may never pass by on the other side. Lord, in your mercy, hear our prayer.

BISHOP NICK: For the times we have failed to live up to our own ideals, we pray for courage and humility as we strive for a more just and equal world. Lord, in your mercy, hear our prayer.This we ask in the name of him whose Son became a refugee and had no place to call his own, even Jesus Christ our Lord, Amen.

THE LORD’S PRAYEROur Father, who art in heaven, hallowed be thy name; thy kingdom come, thy will be done, on earth as it is in heaven. Give us this day our daily bread and forgive us our trespasses as we forgive those who trespass against us. Lead us not into temptation but deliver us from evil. For thine is the kingdom, the power, and the glory, for ever and ever, Amen.

HYMN – Who Would True Valour See

FINAL BLESSING

BISHOP NICK: Almighty God, whose Son Jesus Christ is the Way, the Truth and the Life, grant that we may walk in his way, rejoice in his truth, and live his risen life, and may the blessing of God almighty, the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit rest upon you and all for whom you care, this day and always, Amen.

FINAL MUSIC – The Bird’s Dance (Anonymous)

Broadcast

- Sun 13 Sep 2020 08:10BBC Radio 4