Homeless on streets: Figures fall but 'root causes' remain

- Published

Newcastle rough sleepers tell their stories

There were 4,677 people sleeping rough in England in autumn 2018, according to official estimates.

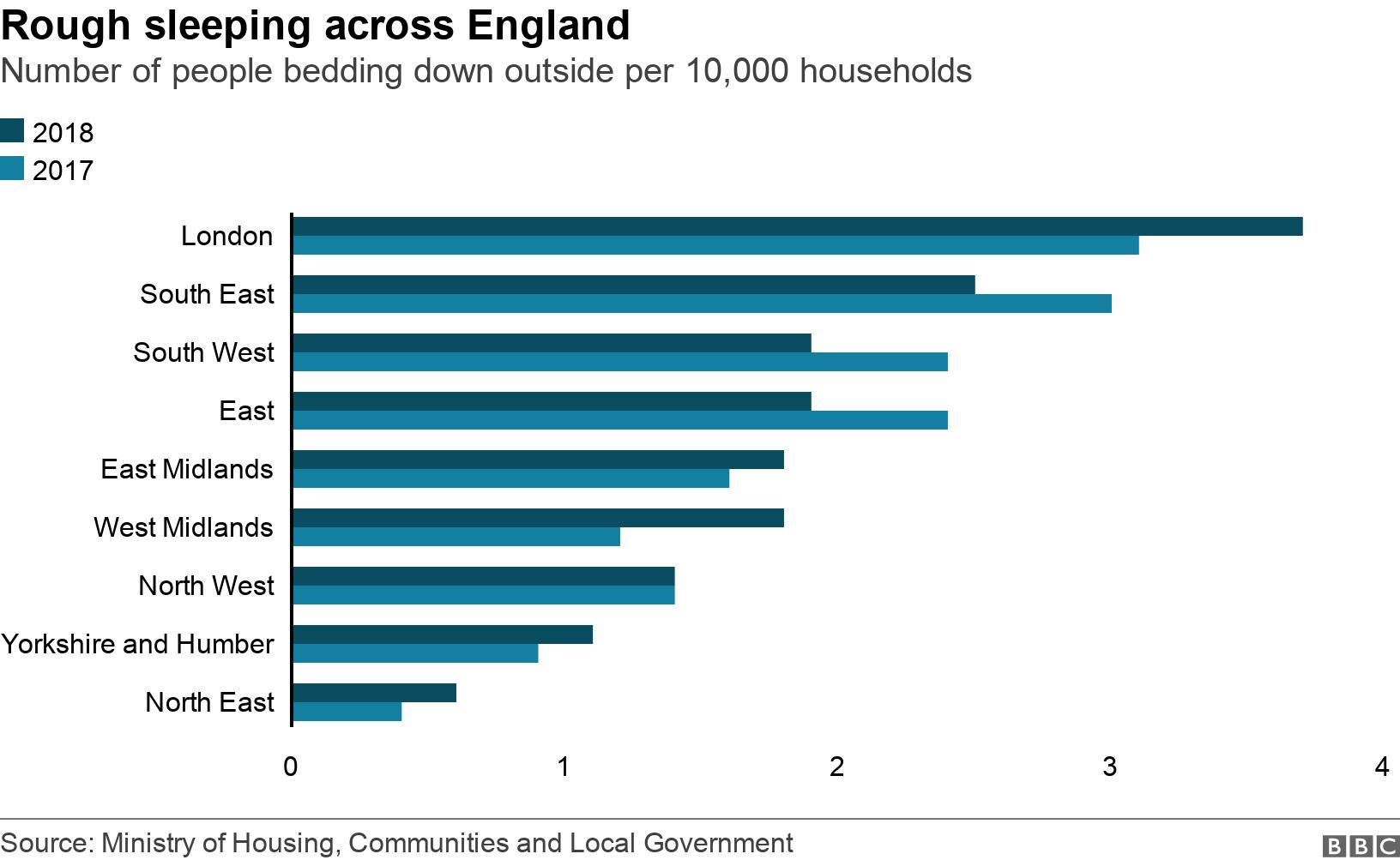

The figure represents a slight fall of 74 on 2017, however rises were recorded in London, the Midlands, north-east and Yorkshire and the Humber.

Numbers are still up 2,909 since the start of the decade, with charities calling for "fundamental action to tackle the root causes".

The government has pledged £100m over two years to tackle rough sleeping.

It will trial schemes in Greater Manchester, Merseyside and the West Midlands where people are given housing without first being required to give up drugs or alcohol, a model which has been hailed a success in Finland.

The figures are only a single night snapshot, with councils either counting or estimating the number of rough sleepers.

London saw an increase from 1,137 to 1,283.

Birmingham went from 57 rough sleepers in 2017 to 91. Manchester's figure increased from 94 to 123.

However Brighton and Hove, which had one of the highest rates of rough sleeping in previous years, dropped from 178 to 64.

Sorry, your browser cannot display this map

Can't see the interactive map? Tap or click here

Charities said that despite the slight overall drop, rough sleeping had "rocketed" by 165% since 2010.

Polly Neate, chief executive of Shelter, said: "The combination of spiralling rents, a faulty benefits system and lack of social housing means the number of people forced to sleep rough has risen dramatically since 2010.

"We welcome many of the things which the government has been doing to seek to improve services for rough sleepers, and numbers do now seem to be stabilising which is a rare piece of good news, but without fundamental action to tackle the root causes of homelessness these measures will only achieve so much."

Chief executive of Crisis, Jon Sparkes said: "It's a damning reflection of our society that night after night, so many people are forced to sleep rough on our streets, with numbers soaring in the capital."

'My girlfriend is worried about me every day'

While the overall number of rough sleepers in England has fallen slightly, in Birmingham it increased 60% in the past year.

A homeless man, Kane Walker, died on the street at the weekend.

James Turner, 41, from Sheldon has been on the streets since June 2018.

He became homeless after he was released from prison, where he had served nine months for assault, and found he was £5,000 in arrears on his house. The day after he returned home from prison, bailiffs came round. He was evicted a short time later.

"They took two grand's worth of leather sofas, my TV, everything.

"I tried to get into a hostel yesterday but they had no space, it was completely packed. They said I could sleep on the floor by the door, I said 'no thanks, I'd rather be on the street'.

"So that's why I'm out here.

"I was found a place in Erdington but when me and my girlfriend got there, there were men there who thought we were someone else and beat us both up, so we left.

"My girlfriend is worried about me every day. She's staying with friends but there's only a single bed and no room for me.

"I don't want to go into hostels. They're full of drug addicts. I'm not on drugs anymore, I don't want to be around all that."

Lewis, aged 29, said he was kicked out of his family home six years ago due to crime and a drug-related lifestyle.

"I just messed up", he said.

"People in Birmingham are really helpful," he said. "I get a lot of hot drinks and that. At the end of the day, Greggs give all of their stuff they haven't sold to outreach workers who give it to us.

"For the life I want to live, I just need money, I need a nine to five, I'm looking for work.

"The number of people on the streets has definitely increased. This time of year it goes up."

When you can't see inside a tent, it makes counting homeless numbers that bit harder, Michael Buchanan explains

Analysis by BBC Reality Check

The official number of rough sleepers published each year by the government does not tell the whole story.

It comes from information collected once a year by local councils. In England councils choose one night in October or November to carry out a street count - they will physically go out and count the people they see sleeping rough on streets in tents or doorways.

Some councils choose instead to make an estimate based on how many people are known to local services like homelessness charities - for example, in rural areas where it may be more difficult to physically count people.

That means anyone who they don't spot - and many homeless people choose to hide themselves for their own safety - or anyone who spends that night walking around, on a night bus or sofa surfing won't be counted.

It also doesn't include anyone staying that night in a hostel or shelter.

There are many more people who are homeless but don't sleep rough, staying instead in temporary accommodation like bed and breakfasts.

Despite the slight drop in the official estimate, Local Government Association housing spokesman councillor Martin Tett, said it was becoming "increasingly difficult" for councils to prevent homelessness and rough sleeping from happening as they faced a "funding gap" of more than £100m in 2019-20.

Communities Secretary James Brokenshire said the figures were "a step in the right direction" but the government was aiming to eliminate rough sleeping by 2027.

"I am clear we need to go further than ever before to build upon today's results and sustain momentum as we move towards ending rough sleeping," he said.

Of the £100m promised by the government to tackle rough sleeping, about £30m will go on mental health help and treatment for substance misuse. The government is putting £50m towards homes outside London for people ready to move on from hostels or refuges.

Councils have so far used new funding to create an additional 1,750 shelter beds and provide 500 rough sleeping support staff, Mr Brokenshire said.

- Published31 January 2019

- Published2 January 2019

- Published30 January 2019