The English city that wanted to 'break away' from the UK

- Published

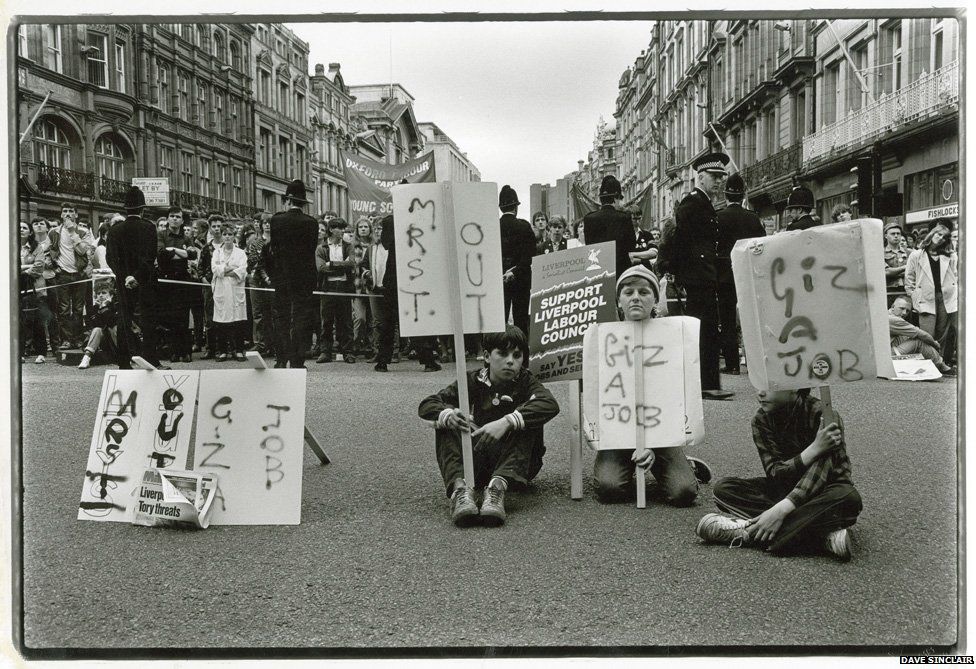

Thirty years ago left-wingers in Liverpool, bitterly opposed to Margaret Thatcher, attempted to oppose central government and go their own way.

It's not just the accent that makes Liverpool feel a bit foreign to outsiders. Geographically and politically, Liverpool is a city on the edge of Britain.

At no time was this truer than in the late 1970s and early 1980s. Once the great port of the British Empire, Liverpool lost 80,000 jobs between 1972 and 1982 as the docks closed and its manufacturing sector shrank by 50%.

Screenwriter Jimmy McGovern recalls typing a CV for his brother in the early 1980s.

"From 1976 onwards it was this litany - Birds Eye, [Fisher] Bendix, Leyland, every one of them - reason for leaving: factory closed, factory closed, factory closed."

The unemployment and poverty caused by the collapse of Liverpool's economy produced the ideal recruiting ground for an ultra-left-wing movement operating within the Labour party. Known as the Militant Tendency, it had sprung from a Trotskyist group called the Revolutionary Socialist League and its goals included widespread nationalisation and embarking on a massive programme of public works.

One of its most influential figures in Liverpool was Derek Hatton, a former fire fighter who was elected to the city council in 1979.

"There was a lot of anger around," Hatton remembers. "Thatcher had come to power and was taking more money off the local authority. So there was a mood in city, which was saying, 'Hang on a minute! What's going on here?'"

Militant supporters were elected to key positions within the Liverpool Labour Party and, in 1983, the same year that Mrs Thatcher won her second general election by a landslide, Labour won the city council elections on a radical socialist manifesto.

It immediately cancelled the 1,200 redundancies planned by the previous administration, froze council rents and launched an ambitious house-building programme targeting the city's most deprived neighbourhoods. Slums were torn down, new leisure centres and nurseries built and apprenticeships created.

The only problem was that the council did not have the cash to fund its projects. But one of Labour's election pledges had been to campaign for more money from central government. And Roy Gladden, a non-Militant Labour councillor both then and now, says the council was confident it could secure the funds it needed.

"In those days, you could negotiate more with government than councils can today. Then we thought we had a case because of the deprivation in the city. We hoped even the Thatcher government would see the need to protect its citizens and that Liverpool, whether they liked it or not, was part of the UK."

At first, the Liverpool Labour council's strategy worked. The Secretary of State for the Environment, Patrick Jenkin, visited Liverpool and was so shocked by the poor housing he saw, he awarded the city an extra £20m. But when the council asked the government for more money the following year, the answer was no.

"They didn't seem to have the right kind of feeling," says Gladden. "They were happy for us to have the factories and make the money that then got shifted to the south, to London. But when it came for that to be returned it didn't happen."

The decision confirmed the "outsider" status that many in the city already felt - among them the musician Peter Hooton, who was then a youth worker on one of Liverpool's poorest estates, Cantrill Farm. "When Thatcher was in power, we felt that she looked at Liverpool and thought: 'Well, they're not really English, are they?'

"Liverpool has always seen itself as separate from the rest of the country. As a city, it has more in common with Belfast and Glasgow than it does with London. There was the big influx of Irish and, because it's a port, it's always been international. We look to America and Ireland - to New York and Dublin - more than we look to London."

In an attempt to balance its books, the council borrowed £100m from foreign banks. It had been part of a coalition of local authorities, including Sheffield, Lambeth and Birmingham, which were campaigning against government cuts. But, one by one, the other councils dropped out and Liverpool was left.

"The mood was very similar to what it was during the Scottish referendum," says Hooton. "People were so politicised - including young people - they were discussing council policy in pubs. They knew the names of the chair of education and the chair of finance. There was no other city like it in that period."

But not everyone in Liverpool supported the council and its confrontational approach to the Thatcher government. In October 1985, thousands of people gathered at the city's Pier Head for a Liverpool Against Militant demonstration. They even released an anti-Militant record.

Meanwhile, Thatcher was so worried that Liverpool was about to go bankrupt that the cabinet considered appointing commissioners to run the city.

Earlier that year, in a last-ditch attempt to force the government to compromise, Liverpool City Council issued 31,000 council workers with redundancy notices. It was meant to be a tactic - a way of buying time and meeting its legal obligation to stay within its budget, says Hatton, who was then deputy leader of the council.

"We sent out a letter to everyone who received a redundancy notice, which virtually said 'don't take any notice of this, we've got to do this, not one of you will lose your jobs.'"

But Labour leader Neil Kinnock was outraged by the tactic.

"If you talk to representatives from the council workers, they were petrified at the possibility of losing their jobs or even temporary redundancy," he says. "You cannot engage in these infantile tactics in order to try to impress government or public opinion if you're going to inflict desperate worry on the people who are going to be most directly affected. You can't play games in those circumstances."

Kinnock made the redundancy notices the centrepiece of his attack on the Militant Tendency at the 1985 party conference. And shortly after, the party started a purge of the Liverpool Militants and the district auditor banned the Liverpool Labour councillors from public office for five years.

Thirty years on, Gladden is once again a city councillor - at a time when what the Liverpool Labour council was trying to achieve may now be within reach.

"What we were trying to say at the time was: 'You can't sit in London telling us what's good for us. Give us the tools to sort our own problems out because we know what's best for our city.' What we were talking about then is what people have been talking about in Scotland."

"The Scots are saying, 'Never mind government deciding what's good for us, we want to decide for ourselves.' Now that devolution argument has spread to England and you've got people in Manchester, Liverpool, Newcastle, Leeds that are ready to make their own decisions. That's what we were saying 30 years ago."

Archive on 4's The Mersey Militants will be broadcast on Saturday 8 November on BBC Radio 4. or you could catch up on iPlayer.

Subscribe to the BBC News Magazine's email newsletter to get articles sent to your inbox.