India election 2019: The looming water crisis politicians ignore

- Published

With voting now over in India's election, one issue that received little attention in the campaign is the country's growing water crisis.

The ruling BJP party says it will provide piped water to every household by 2024 and the opposition Congress party has committed to providing universal access to drinking water.

But there have been warnings of a growing national crisis - one estimate says as much as 42% of the land is currently affected by drought.

So can promises for access to water for everyone really be met?

'Suffering crisis'

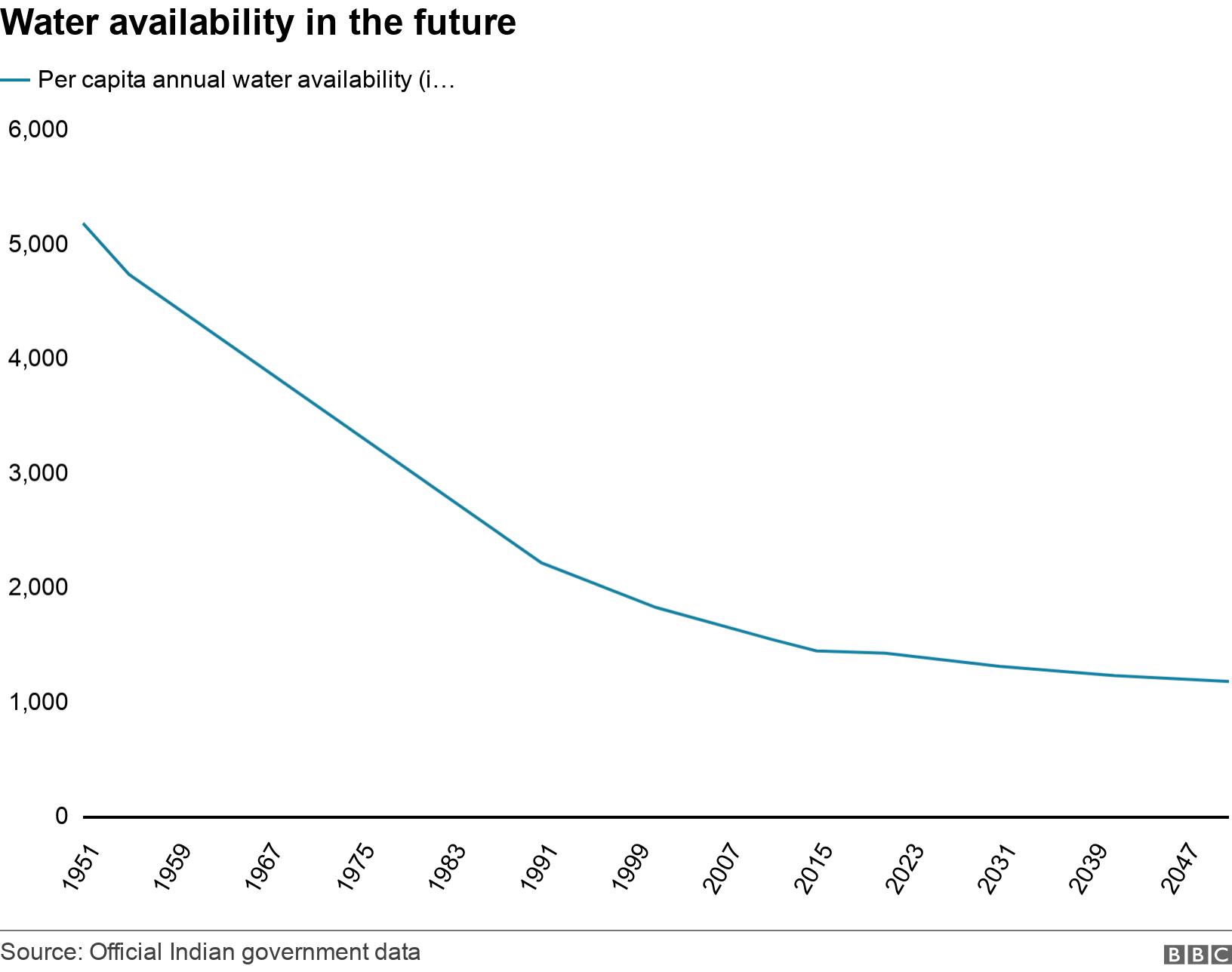

India has over 18% of the world's population but just 4% of its freshwater resources.

The country is "suffering from the worst water crisis in its history", according to a recent government-sponsored report.

Voting for water in a drought-hit state

It warned that 21 cities, including Delhi, Bangalore, Hyderabad and Chennai (Madras), were likely to run out of groundwater by 2020.

Across the country, the report estimates that by 2030, 40% of Indians could be without supplies of fresh drinking water.

Cities growing

The water problem is different for urban and rural India, says Dr Veena Srinivasan, a fellow at Ashoka Trust for Research in Ecology and the Environment.

"Cities are growing so fast that there's no infrastructure that can deliver available water," she says.

By 2030, the country's urban population is expected to reach 600 million.

The long-term concern, however, is the overuse of groundwater in rural India, according to Dr Srinivasan.

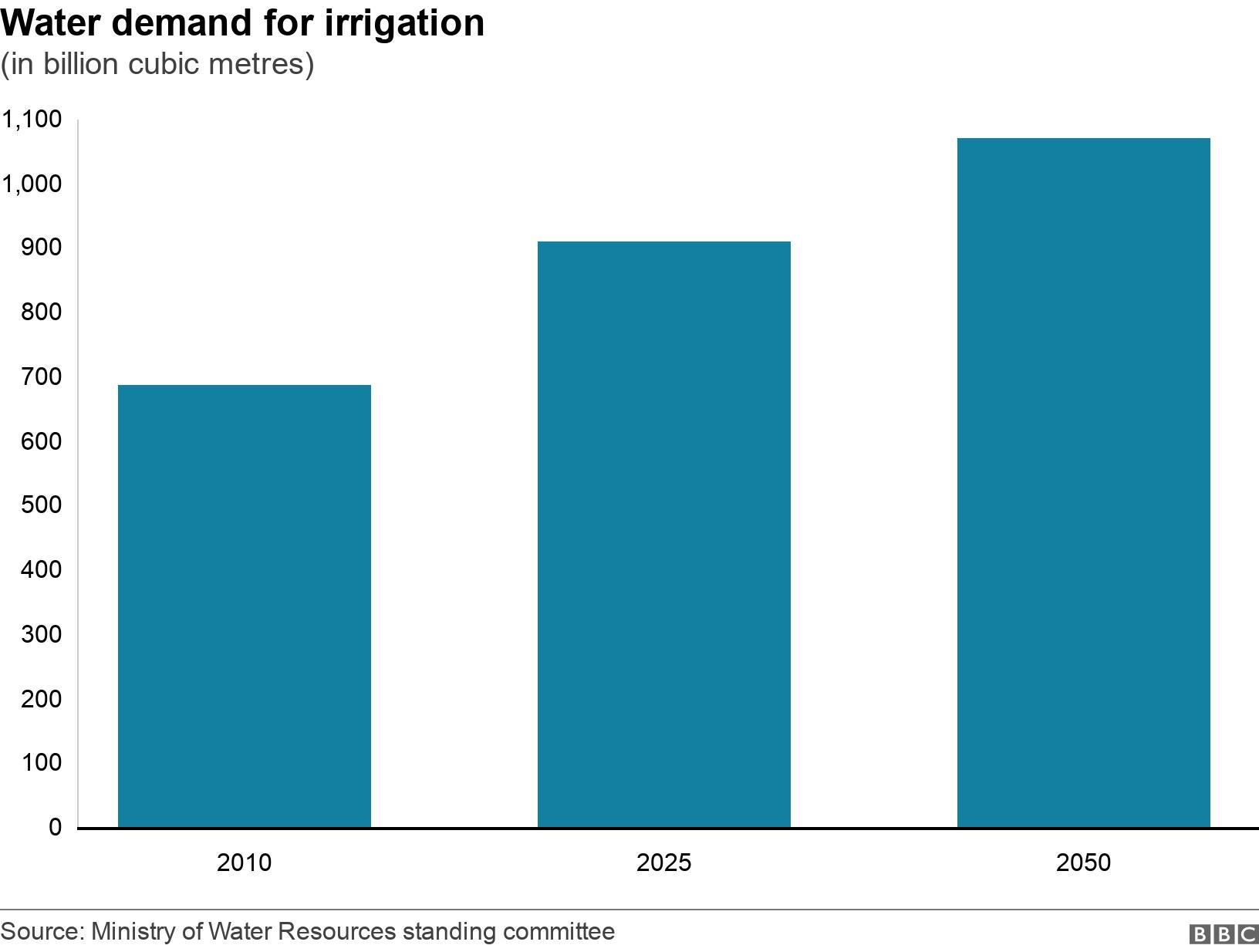

About 80% of water in India goes on agriculture, most of it taken from groundwater stored in rock and soil.

"It's a problem when extraction is more than the recharge," says VK Madhavan, chief executive of WaterAid India.

Major crops such as wheat, rice, sugarcane and cotton are also water-intensive - and water isn't used that efficiently.

Producing 1kg (2lb) of cotton takes 22,500 litres (5,000 gallons) of water in India but just 8,100 litres in the US, according to the Water Footprint Network.

And the water table has reduced by 13% in 30 years, according to India's official Economic Survey for 2017-18.

One important benchmark is the ratio of annual groundwater extraction to net availability.

In 2013, India overall was within the ratio regarded as safe, although, even then, there was more groundwater consumed than replenished in some parts of the country.

By 2018, water levels had declined in about 66% of wells monitored across all regions, when comparing the 2018 pre-monsoon level with the average level for the previous 10 years.

Per capita availability of water was expected to fall from 1,545 cubic metres (400,000 gallons) in 2011 to 1,140 cubic metres in 2050, said a parliament statement in February.

Climate change is also a factor.

Fewer but more intense spells of rainfall cause water to run off the earth rather than soak through to replenish groundwater, says Mridula Ramesh, of the Sundaram Climate Institute.

And droughts can become more common with global warming curbing rainfall in dry regions.

Funding cut

Water use is a state issue in India, but there has been a federal scheme for some years to encourage states to supply safe drinking water to rural areas.

However, funding was cut in the past five years, as the current government prioritised other schemes, such as sanitation.

As of May this year, just over 18% of rural households had a piped water supply, which is only 6% more than five years earlier.

India will start charging industry a water conservation fee from June but some view the proposed fee structure as insufficient.

Has Prime Minister Narendra Modi lived up to his promise of cleaning up the Ganges?

Dr Srinivasan says the key to resolving the problem is focusing on farmers' need for an income, rather than their need for water.

"We need to rethink what is grown, where and how," she said.

Also important are steps to recycle water, and harvest and store rainfall to recharge groundwater.

- Published19 March 2019

- Published6 December 2018