Earl Marchan, of Gorse Hill, Manchester, had never heard of Dick Fuld.

And Dick Fuld, of New York City, had never heard of Earl Marchan.

Mr Fuld was the chief executive of Lehman Brothers, the giant 150-year-old American bank that collapsed on 15 September 2008.

It was an event which placed rocket boosters on an already gathering global financial crisis, the damaging waves of which are still being felt today.

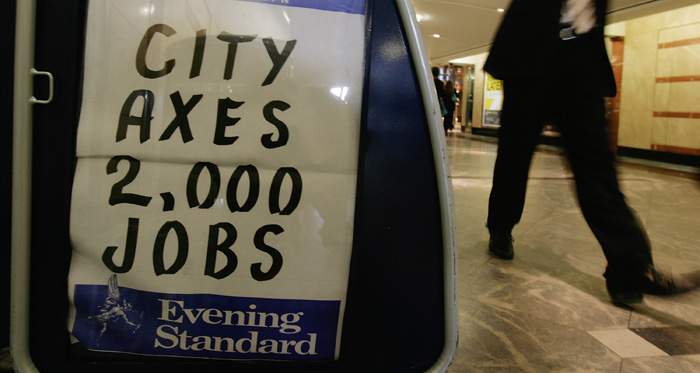

Now, if he’s honest, Mr Marchan didn’t notice very much when Lehman’s fell apart with billions of dollars of losses. The collapse saw 25,000 bankers dumped on the street with cardboard boxes full of their belongings - 4,500 left their jobs at its European headquarters in Canary Wharf, London.

The world - or the part of it which was slowly realising what all this could mean - looked on aghast as a once golden goose of the globally interconnected, hyper-financial system turned to dust.

High finance - that multi-trillion pound cloud that swirled around the world every day - was built on confidence and trust. What was to happen when that trust broke down?

Earl Marchan just got on with his job, like millions of other people unaware of the fire beginning to rage.

“If it doesn’t directly affect you, you’re oblivious to it,” he says, looking back now, 10 years on. “Which makes me feel a bit naive.

“I didn’t see it coming and I don’t think anyone would’ve thought it would have had that big an effect.

“But saying that - once you’re in a recession you’ve got to be in a recession for at least 10 years, haven't you?

“There is no quick fix in a recession, with every growth, you peak and then boom, you've got to plummet haven’t you?”

And, boy, did the world plummet.

Earl Marchan had never heard of Fred Goodwin.

And Fred Goodwin had never heard of Earl Marchan.

Mr Goodwin was the chief executive of the Royal Bank of Scotland, which collapsed on 8 October 2008. It was only saved from oblivion by the injection of tens of billions of pounds provided by millions of taxpayers - one of whom was Mr Marchan.

Fred Goodwin, former chief executive of RBS

He had never heard of collateralised mortgage obligations or any of the other fancy banking products that kept traders hunched over flickering computer screens, earning their millions in salaries and bonuses.

Nor could he have known why the collapse in the value of houses in Sarasota District, Florida, or indeed across the southern states of the US, would matter for his bank account in Britain.

And his job. And his income. For years and years.

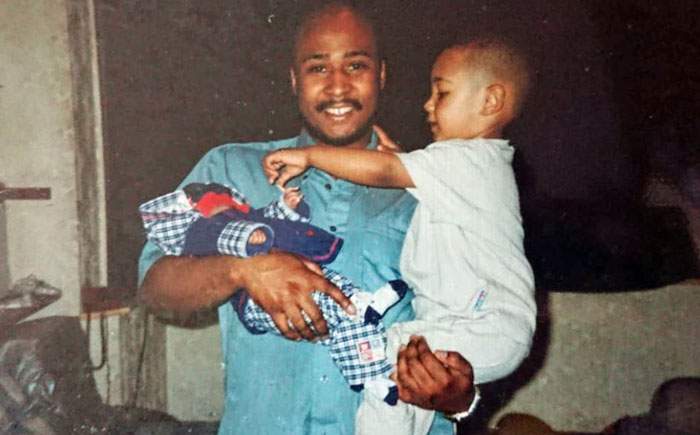

Earl Marchan lost his job shortly after the financial crisis hit and the amount he earns every year now - £20,000 - is only just back to where it was in 2008.

That of course means he is earning less in real terms than he was a decade ago, because prices have gone up.

Making ends meet is more expensive.

Earl Marchan is the living embodiment of the “incomes squeeze”, one of the most economically debilitating effects of the financial crisis.

And for Mr Marchan, read millions of other people in Britain who over the past decade have hardly seen their incomes rise at all.

Or the savers who have seen the returns on what they put away dwindle to almost nothing as central banks slashed interest rates to save the economy.

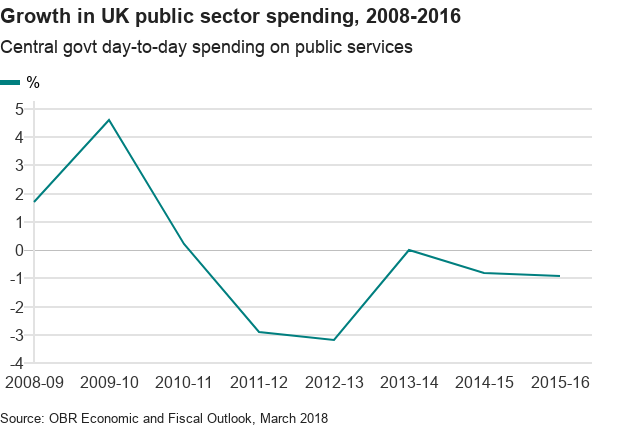

Or the public services which, after the hefty rises of the New Labour years, were suddenly pared back as the government sought to repair its own balance sheet.

The first alarms sounded well over a year before RBS collapsed - the first death rattles for a system built on straw foundations.

Bear Stearns, another US bank, had hit difficulties servicing mortgage loans early in 2007 as the housing market - including that shaky Florida market - turned down and the American economy stuttered.

Unemployment across America was rising and house prices which once may have appeared affordable, but only just, suddenly were not.

“Forced sale” notices started appearing on front lawns across the US as millions of sub-prime homeowners (code for risky borrowers with a high chance of default) fell behind on their payments.

It was often easier for them just to walk into their real estate broker and hand back the door keys, abandoning debts that were then left as “distressed assets” for the banks to deal with.

The US government-backed Federal National Mortgage Association, commonly known as Fannie Mae, was in crisis over the money that had been lent to those struggling homeowners.

Its close cousin, the Federal Home Loan Mortgage Corporation, commonly known as Freddie Mac, was on its knees. Both lost billions of dollars.

It is often said that when America sneezes, the world catches a cold.

Well, this was more than a sneeze. America had influenza. The rest of the Western world was about to catch pneumonia. British banks were closely entwined with the wheezy US economy, billions of pounds worth of assets reliant on the performance of Uncle Sam.

The UK economy started softening. Just as in America, house prices stuttered.

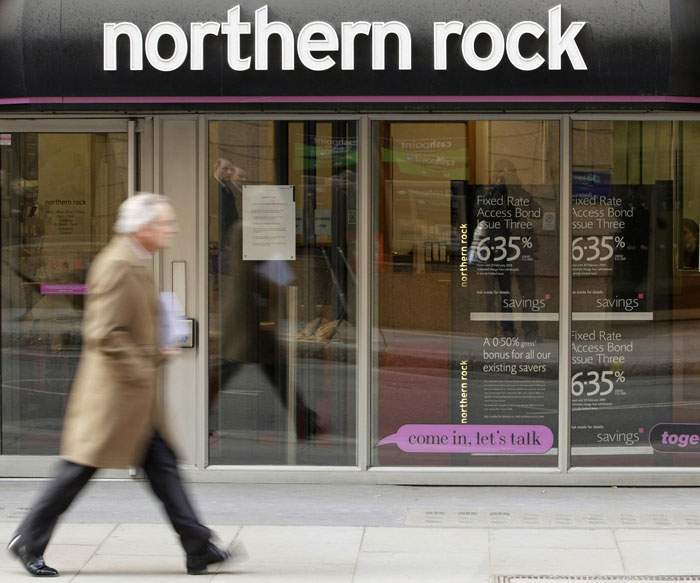

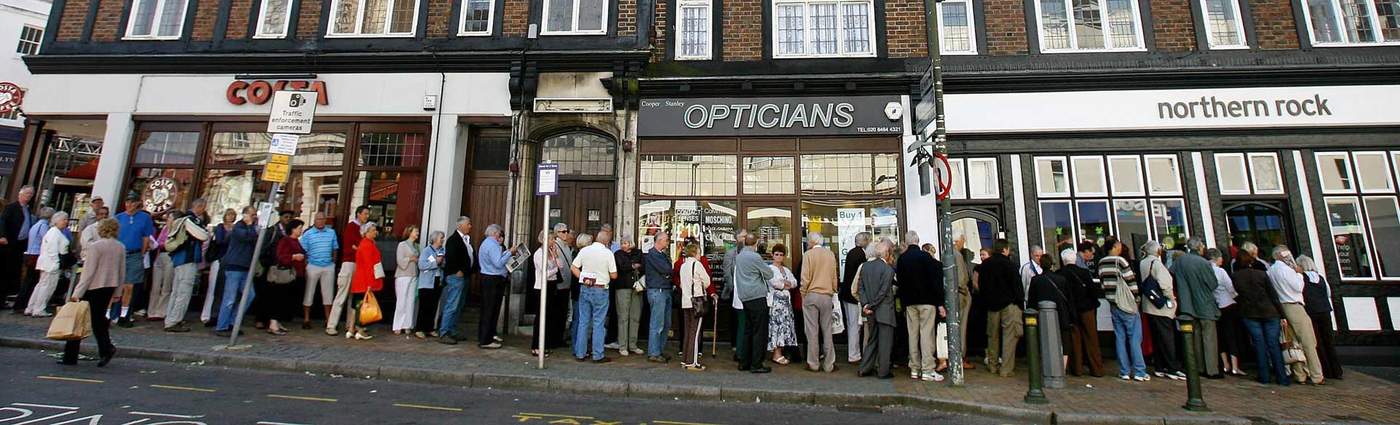

There had already been warning signs. The Northern Rock bank had run into trouble in 2007 and was nationalised early in 2008. Its short-term funding model - for issuing mortgages above the value of the homes they were for - broke down.

That had been inevitable as soon as house prices started falling in the UK, mirroring the US experience. Economic cycles - prices going up and then going down - had not been eliminated.

Northern Rock used the “overnight money markets” to fund its ever-growing loan book which had seen 23 years of record profits. But that market dried up as the value of the bank’s loans started to cause concern among twitchy lenders.

Overnight interest rates that banks use to lend to each other rose to the highest levels for nine years.

Northern Rock’s business model crumbled and the share price fell by 30%. Customers, worried about their cash, queued outside branches. Images reminiscent of a 1930s bank “run” flashed around the world.

“The severity of the recession was certainly much greater than anyone anticipated,” says Karen Ward, former economic adviser to Chancellor Philip Hammond and now chief market strategist for JP Morgan, a bank that itself used the US government’s Troubled Asset Relief Programme in 2008.

“And that is because the global financial system, how it was inter-connected, how the problems passed, and were magnified through the system, was beyond most people’s understanding.”

Alistair Darling, the then chancellor, said that he was amazed that when he asked the banks in Britain for a full inventory of the risks they faced, it was not available.

Alastair Darling, former chancellor of the exchequer

Everything had grown so fast - RBS (which bought 26 banks and other firms in just seven years), Lloyds, Barclays, HSBC, Standard Chartered, Goldman Sachs, UBS, Credit Suisse, Deutsche, Lehman, Merrill Lynch, ABN Amro, Morgan Stanley, Bank of America, JP Morgan - it was out of control.

Hundreds of banks worldwide either went bust, were bailed out or were bought as distressed assets.

Trillions of pounds worth of wealth was destroyed.

“Never before, not even in the 1930s, had such a large and interconnected system come so close to total implosion,” wrote Adam Tooze in his new book How a Decade of Financial Crises Changed the World.

In the dock were the regulators whose “light touch” approach had allowed unsustainable lending to go unchecked and complication and obfuscation in financial products to flourish.

Bad behaviour went unpunished. Rule books were non-existent. The old saying - that the job of central banks (the key financial rule makers) was to take away the punch bowl before the party gets into full swing - had been discarded.

Politicians convinced themselves growth was never-ending and that boom and bust was merely economic history.

The shareholders who craved short-term profits urged bank executives onwards, building bigger businesses through aggressive buyout deals and ever more exotic and risky lending.

At the heart of it all there were the bankers themselves, the financial market men and women who borrowed money short-term, often only for a few days, bought assets, packaged them up and sold them on in an ever more complex series of transactions.

It was all so labyrinthine that not even the bankers really knew where those “golden threads” started. Or cared very much, as long as they were making a margin on every sale and the money kept rolling in.

And when those underlying assets started losing value - like the houses in America that were mortgaged to people who could not afford the repayments - the banks started haemorrhaging money.

Other banks across the world became nervous and started charging more for that lending. Some stopped lending altogether.

That meant “liquidity” dried up, the essential oil of the interconnected system - readily available finance to support the multi-trillion pound cloud of money.

Banks realised that a decade of being nimble - but with very little actual cash on the balance sheet - and voracious for growth, left them naked.

Unemployment rose and suddenly this all became very relevant for millions of people like Earl Marchan who ran shops which served consumers who were starting to feel the pain of contraction.

You check your sales every day and year on year, you notice the decline.

“With the banking issue, it did affect us - in distribution and buying power,” he says.

“Approaching the recession - it affects your sales on a day-to-day basis. You notice the decline.”

With the banking industry on the verge of collapse, finance suddenly disappeared. And companies which employed millions started to struggle.

You may not be able to draw a direct line between the collapse of the banking sector and the failure of a single business.

But a recession of this particular, financial type - very different from the industrial recessions of the 1980s - certainly exposed the weak spots.

And one of those was a High Street chain called Woolworths.

Earl Marchan started as a Saturday worker for Woolworths when he was 15. He earned £2.52 an hour. It was 1993 and Britain was just coming out of two years of recession.

He liked it as a career and was good, rising up through the ranks to full-time staff member, then team leader, assistant manager and manager.

Earl worked for Woolworths for 15 years

The autumn of 2008 seemed to be just like any other. There was the Christmas conference to pick the best-selling toys and ensure the right amount of stock was ready for delivery. Across the country, 25,000 staff were preparing for the busiest time of the year.

Marchan went home feeling pretty good about the weeks ahead. But then texts from anxious colleagues started arriving. There were television news reports that Woolworths, carrying £385m of debts built up in the good times, could be going out of business.

Woolworths was in trouble. The share price had been sinking for a year and as the financial crisis hit, any companies that looked less than 100% solid were quickly washed up in the sense of panic.

2007: Woolworths in Clapham, south London

Consumer confidence fell. Sales fell. Business models soon turned sour.

And in a leveraged, over-borrowed world, problems are magnified and feed through the system very quickly. Trust and faith in a company is built up over decades. But where finance is involved it can drain away at blinding speed.

Suppliers demanded up-front payments in cash. Woolworths struggled to get insurance on the stock it was buying.

Woolworths in Dorking closes for the last time

On 26 November 2008, the shop chain that had opened its first store in Liverpool in 1909 went into administration, unable to pay its ongoing bills and with no willing buyers for the whole company.

In January 2009 the last of its 815 stores closed. Earl Marchan, who had stayed on after Christmas to clear the shop of the last bits of pick and mix and stuffed bears, was out of a job for the first time in his life.

He wouldn’t find another one for a year and eight months.

“It was grim, I'm not going to lie,” he says. “It was a very family-orientated store. People were gutted.”

Trips away stopped for Marchan, his wife and two children. They had to ask for a mortgage “holiday” and hung onto their house by swapping to interest-only - paying off just the interest, not the loan itself.

“I've got three sisters luckily, and all had jobs. So, you know there was a lot of relying on family, and it wasn’t the happiest time for us. We didn't do much, we didn't go many places - the furthest I'd go is up to my sisters in Old Trafford.”

You learn to adapt and you cut back on things

A year before they had been to Barbados to see family and friends. It was to be their last holiday abroad.

His then wife, Miriam Chin, said that the family had to economise.

“You don’t go and buy extravagant things from Tesco,” she says. “You shop around, and you go to places where there’s less choice because you can’t indulge in other things. You go to the Aldis and the Lidls, where you get your basic fruit and veg.

“But you learn to adapt and you cut back on things.”

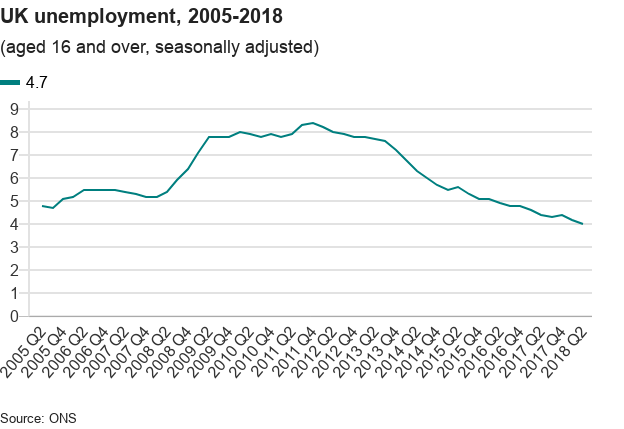

By the end of 2011, almost 2.7 million people were looking for work as the recession bit. Some firms, like Woolworths, went bust. Others contracted as consumer demand waned. The quarterly unemployment rate grew to 8.4%, the highest since 1995.

But after the initial shock, a surprising thing happened. Unemployment fell as jobs started to be created - the UK’s labour market flexibility acted as a shock absorber.

Mr Marchan found work - well-paid work - running service station forecourt shops. Plentiful employment is not the normal path of events following a recession and a subsequent period of low growth. And the explanation for it lies in two trends that were apparent in the economy - one to do with the financial crisis and one that wasn’t.

The first was the flood of cheap money that was created by the Bank of England to shore up the financial system.

The impact of the crash was felt across the UK's high streets

This was “quantitative easing” - the Bank creating billions of pounds worth of “new money” (not literally printing it - this was done digitally) to buy assets, such as government and company debt, and allow firms to borrow cheaply. Some described it as a necessary drug to keep the patient - the UK economy - alive.

The Bank also slashed interest rates to record lows. At the beginning of November 2008 rates were at 4.5%. By March 2009 they were down to 0.5%. They wouldn’t rise again for eight years.

Ultra-low interest rates made borrowing money for companies very cheap, as well as boosting anyone with a variable mortgage who found their monthly repayments slashed. People had a little more money to spend in the shops.

There are positives, but no doubt for the average UK worker it’s been a struggle in the last 10 years.

The effect was to make the recession more shallow than expected. It allowed companies which would otherwise have gone under or certainly stopped investing, to keep going and - to an extent - keep expanding.

People were kept in post, helped by employees regularly offering to work fewer hours for a period or accept pay cuts. By May 2018, the unemployment rate stood at 4.2%, the lowest since the mid-1970s.

“People have essentially priced themselves into work, so employment has actually held up remarkably well,” says Ms Ward.

“The employment statistics suggest the economy is doing fantastically well.

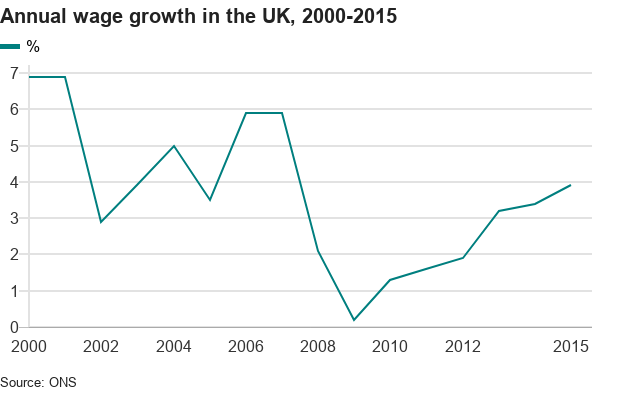

“But if we look at what has happened to guarantee that, it’s people accepting real wage declines.

“The upside to that is of course people have maintained their jobs, and our housing market has been more stable than would have otherwise been the case.

“So there are positives, but no doubt for the average UK worker it’s been a struggle in the last 10 years.”

When Mr Marchan’s job running petrol service stations ended - the petrol firm he was working for was taken over - he ended up at the NHS as a receptionist, earning less than he had been a decade earlier. Again he had to give things up, being forced to sell his Audi car just a year after buying it.

“Each time I lost a job, I’d say it cost me five years. I’m still 10 years behind what I’d like to be.”

That was common for many millions of people as real earnings rose slower than prices (inflation).

In 2018, at the age of 41, and after four years working for the NHS, does he have any disposable income?

“No! With two children at university?” Mr Marchan answers with a laugh.

And if he was to get an unexpected bill at the end of the month of £50, how would he pay it?

“On my emergency credit card, pay it off a little bit each time,” Mr Marchan answers.

He pauses. “I did that just last month. Got a speeding ticket.” It will take the rest of the year to clear it.

It was a warm April day at Cheltenham Racecourse and David Cameron, who had made a bit of a name for himself striding around with no notes when delivering speeches, decided on a different approach for that year’s Conservative Spring Conference.

The Leader of the Opposition spoke for 35 minutes behind a lectern. There was nothing flash this time, just a sober assessment.

“The age of irresponsibility is giving way to the age of austerity,” he told that assembled audience of Tory faithful in 2009.

“The money has run out. The alternative to dealing with the debt crisis now is mounting debt, higher interest rates and a weaker economy. Unless we deal with this debt crisis, we risk becoming once again the sick man of Europe.

“Our recovery will be held back, and our children will be weighed down, by a millstone of debt. So this is no time for business as usual.”

Four days earlier, Alistair Darling, the Chancellor, had revealed that the government deficit - that is the difference between what the government receives in taxes and spends on public services - had ballooned to £175bn.

It was the largest deficit in history.

Greece found this to its cost with multiple multi-billion euro bailouts from the European Union and the International Monetary Fund.

International creditors - those firms which had previously been so keen to buy up state debt - were charging more for their money or had disappeared altogether, leaving the Greek government with bills it could not pay.

Each bailout came with stringent austerity measures attached, including sharp cuts in public service provision. There were riots in the streets.

In Britain there were plenty of demonstrations as the public sector cuts bit.

“The new Budget forecasts suggest that the financial crisis and the economic damage associated with it opened an additional structural hole in the public finances of around 5.8% of national income or £86bn a year in today’s terms,” said Robert Chote, head of the Institute for Fiscal Studies, at the time.

There was a public sector pay freeze followed by a 1% pay cap which has only been lifted in the past 12 months.

The government announced £11bn of cuts to welfare spending.

Outside the protected departments of health and overseas aid, cuts of 25% were planned over five years.

“We are looking at the longest, deepest sustained period of cuts to public services spending at least since World War Two,” Chote said.

Taxes also rose, by £8bn, for individuals and businesses by 2014-15.

“Balancing the books” became the government’s mantra - setting targets for itself to match the amount it spent on public services to the amount it collected in revenues from taxes and investments.

The targets to eliminate what is called the deficit were continually missed. The economy performed more poorly than expected, the government failed to make the planned cuts and global events - such as the eurozone crisis - knocked Britain off course.

Some economists blamed austerity itself for taking so much spending power out of the economy that it had a depressive effect.

For the Conservatives, on the terms they had set themselves, the medicine did work.

The public finances were in surplus by £2bn for the month of July, the largest in 18 years. At the same time, borrowing in the April-to-July period fell to its lowest level since 2002.

The effects of the financial crisis are still deep. Overall, government debt is still huge - £1.8tn. Growth is still low by historic standards.

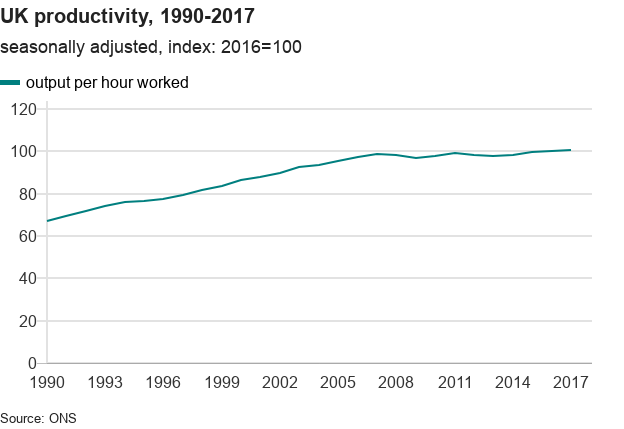

Incomes are rising only just above the rate of inflation. Productivity is poor.

The average percentage of British disposable income that is saved is 4.1%, the third lowest since records began in 1963. In the 1990s, it was as high as 14.7%. “Putting money away” remains relatively unattractive.

And it is clear why. A lump sum of £1,000 saved for a decade from 1997 at the interest base rate would have paid back £1,653 by 2006, according to figures compiled for the BBC by Savings Champion.

A lump sum of £1,000 saved for a decade from 2007 would have paid back £1,150 by the end of 2016.

Savings have not been paying back very much for an awfully long time.

Those low interest rates - coupled with the vast expansion of monetary support from the Bank of England - also contributed to rocketing house prices in some parts of the UK. Over the past decade, the average house price has increased by 25% (ONS). In London and the south-east, and also in Manchester and other cities, the increase was much higher.

The Marchan family may have had to switch to an interest-only mortgage during the hard times, but they have at least seen the price of their house in Manchester rise.

“On my street, when we bought my house it was £42,000,” says Mr Marchan. “They’re going for £180,000 on this street.”

Even that apparent good fortune leaves Mr Marchan worried for his sons, who are studying architecture and biomedical sciences at university. Even in professional jobs they may struggle to raise the kinds of deposits now needed to buy a house in many parts of Manchester.

“I say it to them, once they finish university, I don’t know how they’re going to get on the property ladder anyway.”

The Bank of England insists that regulations covering the banks and the wider financial services sector are now far more robust.

Never say never but it appears a similar crisis could not happen again.

The government has signalled the end of austerity as the public finances look in a better state.

The American economy is strengthening. Global growth is stronger.

There are reasons for optimism.

But the effects of the financial crisis still persist, a decade after Dick Fuld became the face of all that was wrong in the interconnected, high-rolling financial world.

There are still the structural issues. What is the correct role of government in supporting growth and managing risk? How might an industrial strategy help that? And how can the rules of globalisation and international trade be changed to ensure that no groups are left behind?

But there are also rather less tangible strands that are no less important for the economic health of us as individuals, for the UK itself and for the world economy.

Those strands are around sentiment, confidence and the return of sensible risk-taking. Emotions - because so much of economics is about emotions and human behaviour - have been so damaged, destroyed by the events of that crazy autumn of 2008.

At the beginning of this year I interviewed Larry Fink, the head of the world’s largest investment fund BlackRock, which invests trillions of dollars in governments and businesses. What he says moves markets and makes prime ministers sweat.

I asked him what was holding back economies, if we think about economies being fundamentally the millions of decisions made every day by people like Earl Marchan who might have an extra pound at the end of the week. Or might not.

“Fear,” he said. “Fear of running out of money.” Ten years after the world nearly did just that.