The Art of Innovation – the secrets behind the pictures

In The Art of Innovation Sir Ian Blatchford, Director of the Science Museum Group, and the Science Museum’s Head of Collections, Dr Tilly Blyth (pictured), explore how art and science have inspired each other.

Some of the objects and artworks in the 20-part series have rarely been seen, and all of them have fascinating backstories.

Here, series producer Adrian Washbourne reveals some of the hidden histories behind five of the subjects.

Photo © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

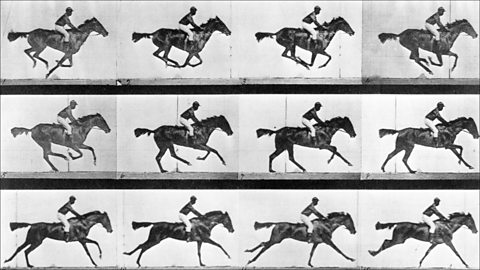

1. Eadward Muybridge: Horse in Motion

Capturing a horse in motion

How Eadweard Muybridge revealed a horse's true running gait for the first time.

It was a rumoured $25,000 bet that secured flamboyant photographer Eadweard Muybridge’s fame in capturing a horse’s movement. Muybridge's instantaneous photography made motion visible and from the late 1870s he took thousands of images studying humans and animal movement.

But the horse was the source of all transport of importance, so to understand its movement was critical: does it have all four feet off the ground in a gallop? One person with a stake in the debate was the ambitious Leland Stanford – founder of Stanford University, and owner of champion racehorses – with an obsession to breed yet faster champions.

To settle a bet he’s said to have made with the San Francisco Chronicle, Stanford commissioned Muybridge, armed with rows of cameras and trip wires, to capture split-second movements from his stock farm in Palo Alto. The horse did indeed lift all four legs off the ground during its stride. However, this was not in the front-and-rear extended posture some had expected, but with all four feet tucked under the horse.

Painters such as Edgar Degas and Thomas Eakins loved the realism and used Muybridge's photos to move their own work closer to reality.

2. Nasmyth's Moon

Looking at the Moon

How James Nasmyth's moon observations and photographs foreshadowed the Apollo missions.

Stanley Kubrick may have been among the first artists to create convincingly realistic images of outer space for the movies, but in the world of still photography, even in the 19th century, he had many predecessors.

The most extraordinary was James Nasmyth, a retired engineer from Edinburgh and inventor of the steam hammer, who meticulously re-created the lunar surface using plaster, modelled from his nightly moon observations through his 20 inch telescope.

His book, The Moon, is one of the true classics of astronomy – containing photographs of his cleverly-lit plaster casts with all their scientific detail of shadowy craters and mountains. Intriguingly, in anticipation of Apollo 8’s famous Earthrise photo, Nasmyth’s book ends with a similar view of the Earth as if seen from the moon. It kick-started a market for artworks depicting how planet Earth would look from near and distant planets, to reinforce the popular late 19th century notion that there are beings like us on other worlds in this and other solar systems.

3. Stopping time on camera

The instant camera revolution

The many variants of the instant camera and the impact of the colour palette on art.

The ability to freeze time has intrigued artists for decades. Capturing things too quick for us to see, it offered a window into our world beyond what we knew it to be. For those caught adrift in the accelerating speed of the early 20th century, fleeting time felt more understandable and safe by breaking it into manageable chunks.

Photographs appeared to stop time and unlike a painting, had an immediacy. The arrival of Edwin Land’s instant Polaroid camera which packs all the operations of a darkroom inside the film itself, opened this window up to all, and by 1956, one million people were snapping instant memories – both planned and accidental.

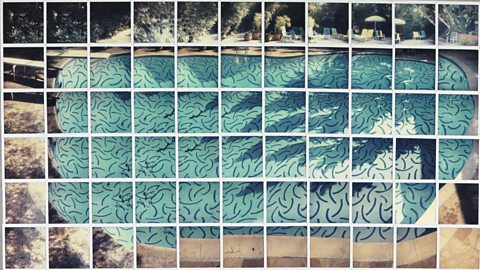

Artists were also drawn to Polaroid snaps as a new art form. For Andy Warhol the Polaroid picture, with its strict size and white borders, was inherently Pop. David Hockney overcame his ambivalence to photography, taking a series of Polaroid snapshots of a single scene from multiple perspectives and at different times, and recomposed them into grids. He was effectively “drawing with a camera”. It was, he believed, much closer to how we see a scene in real life.

4. Supersonic

Pushing the outside of the envelope

How a picture revealed the physics of objects travelling at supersonic speed.

It’s not just a work of imagination, it’s also one of science: this is the first abstract image ever to be commissioned by the aviation industry and shows how, as an object approaches the speed of sound, the air ahead of a bullet or aeroplane becomes compressed and there isn’t enough time for the squeezed air to get out of the way. There’s no “barrier” as such, but as the object reaches supersonic speed, it passes through this zone of compression leading to shockwaves in the form of concentric cones diverging from its nose, causing a startling sonic boom.

When the sound barrier was officially broken by the American Bell X-1 aeroplane in 1947, the demand to convey supersonic travel to a now curious public needed the hybrid of an artistic image and a technical diagram. Roy Nockolds was the man to do it. He’d become a propaganda artist for the RAF during WW2 with access to the highly secretive world of test flying at the Royal Aeronautical Establishment in Farnborough. The picture symbolised the hopes and ambitions of the post war nation, when technology will push the very bounds of physical laws.

5. Coalbrookdale by Night

Coalbrookdale by Night

How a controversial painting acquisition forged new ways for art and science to connect.

An art collection at the Science Museum may come as a surprise, but images have been part of the Museum’s history since the beginning. In the 1950s, the purchase of one painting led to stern words between the director and curators over what purpose art played in the museum.

The director Frank Sherwood-Taylor bought Coalbrookdale by Night in 1952, a vivid scene of raging furnaces in Shropshire, the birthplace of the industrial revolution. He was opposed by Fred Lebeter from the Metallurgy department who complained that the painting was "of little value in illustrating the actual progress of metallurgy." Sherwood Taylor’s view that "this kind of representation is … what is required to … fire the imagination of the spectator" luckily won the day.

The painting is all about fire and imagination. Philippe-Jacques de Loutherbourg, the artist, was also famous for his set designs at Drury Lane, and this vibrant image of Coalbrookdale makes the most of his theatrical training. You can almost see the flames flickering under the billowing smoke as workers toil to feed the furnace at the heart of the gorge. Those same furnaces produced the vast ribs for the Iron Bridge, which now makes the area famous.

Photos 1, 2, 4, 5 © The Board of Trustees of the Science Museum

Photo 3 © David Hockney Studios

You can explore other treasures of the Science Museum Art collections online.

-

![]()

The Art of Innovation

The Art of Innovation is a partnership between Radio 4 and the Science Museum exploring art and science. Sir Ian Blatchford, Director of the Science Museum Group, and the Science Museum’s Head of Collections, Dr Tilly Blyth, present a series exploring how art and science have inspired each other.

Art and Science on Radio 4

-

![]()

The Art of Innovation

Ian Blatchford and Tilly Blyth explore how art and science have inspired each other.

-

![]()

The Infinite Monkey Cage

A witty, irreverent look at the world through scientists' eyes. With Brian Cox and Robin Ince.

-

![]()

The Life Scientific

Professor Jim Al-Khalili talks to leading scientists about their life and work.

-

![]()

Moving Pictures

A series looking look at great artworks, photographed in incredible detail.