Arthur Hurst: The Man Who Filmed Shell Shock

Martin Hurst has always known he had a famous grandfather called Sir Arthur Hurst but only recently has he found out why his father’s father had the reputation he did.

A “precociously successful” doctor, Hurst started his career at Guy’s Hospital in 1906. He went on to found The British Society of Gastroenterology (their annual dinner is named after him), but it is the lasting record of his work during World War One (WW1) that truly sets Dr Hurst apart. Marking the centenary of this seminal work, Home Front dramatizes Arthur Hurst and his achievements at Seale Hayne Military Hospital.

In April 1918, under Hurst’s command, Seale Hayne opened as a military hospital dedicated to treating soldiers with neurological problems that were categorised as shell shock. Built as an agricultural college, Seale Hayne’s quiet, rural location near to Newton Abbot was thought to be ideal for convalescing soldiers suffering with shell shock. Its patients had problems with using their bodies even though there was nothing physically wrong with them. Their symptoms included disrupted gaits, paralysis, mutism and uncontrollable spasms or tremors.

Unprecedented casualties

By this time, shell shock had become a medical emergency. Not only was the number of casualties unprecedented but little was known about how to treat them. Many different methods were tried, from electric shock therapy to putting patients in different coloured rooms, and success rates varied considerably. For some patients it was thought that nothing could be done. Archivist Tim Whiteaway, who has researched Hurst’s WW1 work, said, “In worst case scenarios a lot of these people were just left. They decided there was no treatment for this type of incident. In some cases some of these soldiers had been languishing in wards for anything up to three or four years.”

Eager to improve understanding of shell shock and promote successful treatments, the Medical Research Committee provided funding for Hurst to make a film of his work. Hurst called it War Neuroses, the term he preferred to "shell shock".

Hurst recorded his patients before and after treatment with intertitles stating their diagnosis, symptoms and, most importantly, the speed of cure. For example, Private Richards had a “hysterical gait following shell-shock” and was “cured by persuasion and re-education on the day of admission”. In August 1918 Hurst declared, “We are now disappointed if complete recovery does not occur within 24 hours of commencing treatment, even in cases which have been in other hospitals for over a year”.

A maverick approach

Hurst’s bold claims took his professional contemporaries by surprise. Other doctors treating shell shock, who had expertise in psychology, could not believe that Hurst, a general physician, was having more success than them. Perhaps Hurst’s personality also rubbed his peers up the wrong way. He is said to have had a deep distrust of tradition and a maverick approach to treating his patients. Mr Whiteaway said, “He didn’t (have) much truck with the general militaristic aspect of following orders. In fact, the first hundred patients he brought here [Seale Hayne], he brought without permission… And he was paying the staff out of his own pocket for the first month.”

There is another aspect of Hurst’s film that could be further evidence of his pioneering attitude. Clearly inspired by Geoffrey Malins and John McDowell's widely seen 1916 film The Battle of the Somme, Hurst includes a final sequence titled The Battle of Seale Hayne. Filmed on Dartmoor, convalescing shell shock patients re-enact ‘going over the top’. Some feign injury or death and are then collected by stretcher bearers.

Viewed 100 years on from its production, this section of Hurst’s film can sit uncomfortably with the viewer – should traumatised soldiers be made to pretend to be back at the Front? Mr Hurst, Arthur’s grandson, suggests an alternative view likening the mock battle to “modern day drama therapy” where patients can “re-experience a traumatic event in a safe environment”. No definite conclusions can be drawn as it cannot be known how the soldiers were prepared for the re-enactment, how they felt about taking part or if it had any effect on them afterwards.

Apparent trickery

More recently doubt has been cast over the authenticity of Hurst’s reporting of his success. One of his case studies, Sergeant Bissett is presented as being filmed before treatment in September 1917 and after treatment in November 1917. However, Professor Edgar Jones has identified that in the September sequence and the November sequence the same group of nurses and smoking chimneys can be seen in the background. Professor Jones says this demonstrates that both sequences were filmed at the same time after treatment and Sergeant Bissett was re-enacting his original condition.

Mr Hurst thinks focusing on this apparent trickery in Hurst’s film does not do justice to his grandfather’s work. “It should be treated properly and not sensationalised. It might have been reconstructed; they might have lost the original footage”. The actor Mark Heap, who plays Hurst in Home Front, added, “The danger is to say he was a bit of a charlatan but I don’t think that’s fair. I think he was very genuine, clearly very medically qualified and he just tried a different way with his patients.”

Dramatising a real life character

Actor Mark Heap discusses his role in Home Front; the pioneering doctor, Arthur Hurst.

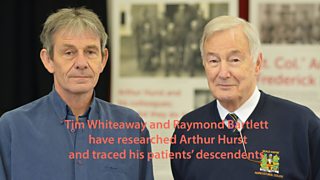

Hurst and his colleagues at Seale Hayne claimed their cures were permanent but no follow up studies were ever done. One hundred years on, often only starting with a surname, Mr Whiteaway and Raymond Bartlett, the chairman of the Seale Haynian Alumni Club, profiled a number of Hurst’s patients and made contact with their relatives. “Particularly with his [Hurst’s] critics in mind, we thought we must try to trace the descendant relatives to find out what happened to those men”, said Mr Bartlett.

Their research, which details the lives of about a dozen Seale Hayne patients, was presented as an exhibition at Seale Hayne, which is now owned and run by the Dame Hannah Roger’s Trust. Mr Bartlett said, “Those patients we have discovered so far, they did all lead able-bodied lives afterwards. There were one or two who were nervy but they did a job of work afterwards and some of them lived to quite an age as well.”

The exhibition included letters from patients which all express considerable gratitude to Hurst and illustrate the relationships he developed with his patients. One says, “I don’t want to gush, but I do realise the immense amount of trouble and skill spent on pulling me back into rational working order.” Hurst’s grandson, Martin, added that when Hurst died (before Martin was born) there were loads of letters of sympathy from patients. While Hurst’s professional life is well-documented, he has remained a mystery to his own family. Martin said, “You can see he was a very warm person as well as being very skilled, he related to his patients very well. As far as family was concerned he didn’t really have time for them.”