The original emoji: Why The Scream is still an icon for today

11 April 2019

Norwegian artist Edvard Munch was the tortured genius behind one of the best-known images in history. TOM CHURCHILL looks at the enduring appeal of The Scream, now on display at the British Museum, and how it reflects the anxieties of our age.

Most of art’s iconic masterpieces are renowned for their beauty. Think Leonardo’s smiling Mona Lisa, Vermeer’s luminous Girl with a Pearl Earring and Botticelli’s nude goddess, Venus.

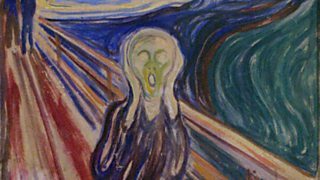

But there’s one glaring exception in the list of all-time greats: Edvard Munch's The Scream. With its pale, hairless figure holding its head in its hands, mouth agape in a tortured howl, it was perhaps an unlikely candidate to become one of the most recognisable and reproduced images of all time.

Yet this visceral, doom-laden work – a reflection of the Norwegian artist’s troubled state of mind at the end of the 19th Century – has grown to permeate every aspect of popular culture, from film and TV to memes and tattoos.

You’ll find adaptations and parodies of it on student bedroom walls, on protesters’ placards and in political cartoons. It’s the first painting to have spawned its own emoji – the ‘face screaming in fear’. It has become the ultimate image of existential crisis, the original Nordic Noir.

“One evening I was walking along a path; the city was on one side and the fjord below,” Munch wrote, describing his inspiration for the painting.

“I felt tired and ill. I stopped and looked out over the fjord — the sun was setting, and the clouds turning blood red.

“I sensed a scream passing through nature; it seemed to me that I heard the scream. I painted this picture, painted the clouds as actual blood. The colour shrieked. This became The Scream.”

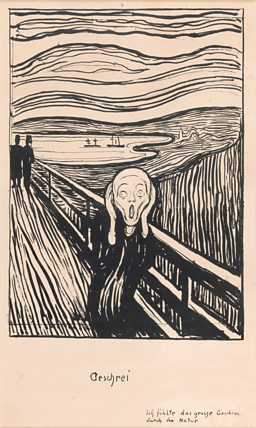

An 1895 lithograph print of the work, one of several versions Munch created, is the main draw of a new exhibition, Edvard Munch: Love and Angst, at the British Museum in April. It’s the largest show of Munch’s prints in the UK for 45 years, and will offer a revealing look into his turbulent psyche.

Born in the village of Ådalsbruk in 1863 and brought up in Kristiania (renamed Oslo in 1924), Munch’s life was shaped by a strict upbringing in an oppressively religious household, marked by tragedy and emotional stress.

His mother and older sister both died before Munch turned 14, his father died 12 years later and another sister was committed to an asylum, suffering from bipolar disorder. Munch himself also struggled with his mental health throughout his life.

“For as long as I can remember I have suffered from a deep feeling of anxiety which I have tried to express in my art,” Munch wrote. “Without this anxiety and illness I would have been like a ship without a rudder.”

He studied at the Royal School of Art and Design in Kristiania before travelling to Paris and Berlin, embracing a bohemian lifestyle, cultivating a network of fellow artists and thinkers, and developing a style that broke with artistic tradition.

Munch became increasingly preoccupied with the tensions caused by urbanisation, advances in science and the moral dilemmas of a world on the brink of great change.

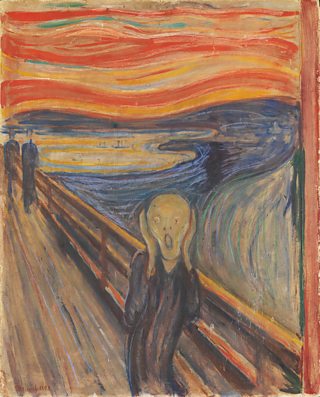

In 1893 he painted what would be the first of four versions of The Scream, which is today housed at the National Gallery of Norway in Oslo. The painting was stolen in 1994 but recovered undamaged shortly afterwards in a sting operation.

The city’s Munch Museum houses a pastel version from the same year, along with a second painted version from 1910 – which was also stolen, in 2004, and also later recovered.

A second pastel version, dating from 1895, is the only one of the four in private hands, and sold for $120 million at auction in 2012 – a record at the time. Finally, a lithograph stone was produced in 1895 – and it is a rare black-and-white print from this that the British Museum will display.

Theories abound as to the influences behind key elements of the work. The red sky has been linked to the effects of the Krakatoa volcano in 1883 which led to spectacular colouring in the skies above Europe for many months; as well as to the phenomenon of Mother of Pearl clouds.

The central figure has been linked to a Peruvian mummy Munch may have seen at the 1889 Exposition Universelle in Paris, and also to a giant Edison light bulb displayed at the same event.

Author Kelly Grovier suggests: “Given Munch’s anxieties about modern culture, it is easy to see how the newly patented symbol of science, the light bulb, may have merged in the artist’s mind with the mien of the evocative mummy, an unsettling relic of a civilization long since extinguished.”

But it is the ambiguous, unknowable nature of this strange figure which is the key to The Scream’s universal appeal, argues art critic Jonathan Jones. He writes in The Guardian: “By removing all individuality from this being, Munch allows anyone to inhabit it. He draws a glove puppet for the soul.”

And if Munch’s work is indeed an expression of his anxiety at a turning point in history, in a world increasingly cut loose from old traditions, there are clear parallels in the world of today. This is surely why The Scream retains its power despite its ubiquity: it’s a mirror of our own contemporary fears. Inside, aren’t we all screaming too?

Edvard Munch: Love and Angst is at the British Museum, London, from 11 April – 21 July 2019.

A version of this article was published in January 2019.

Tattoo artist Lucky Soul Tattoo posted this image of a Scream tattoo on Instagram - one of many examples of Munch-inspired body art.

More Munch

-

![]()

What is the meaning of The Scream?

Edvard Munch’s portrait of existential angst is the second most famous image in art history – but why?

-

![]()

Munch inspired by 'screaming clouds'

Norwegian scientists have put forward a new theory to explain the inspiration behind The Scream.

-

![]()

Munch's The Scream and the appeal of anguished art

BBC News Magazine's Jon Kelly asks why such agonised, visceral works of art are so highly sought-after.

-

![]()

Witness: The Theft of the Scream

In 1994 the painting was stolen from a Norwegian museum. It was recovered in a daring undercover operation.

More from BBC Arts

-

![]()

Picasso’s ex-factor

Who are the six women who shaped his life and work?

-

![]()

Quiz: Picasso or pixel?

Can you separate the AI fakes from genuine paintings by Pablo Picasso?

-

![]()

Frida: Fiery, fierce and passionate

The extraordinary life of Mexican artist Frida Kahlo, in her own words

-

![]()

Proms 2023: The best bits

From Yuja Wang to Northern Soul, handpicked stand-out moments from this year's Proms