Domesday Project reborn online after 25 years

- Published

Domesday Project producer Alex Mansfield shows Rory Cellan-Jones life in the UK as recorded by the 1980s project

A good idea, combined with the right technology, can change the world.

Facebook, Wikipedia and the wheel have all shown this to be true.

25 years ago, the BBC dreamt up a similarly inspired scheme.

However, in the case of the Domesday Project, it was the tech that doomed it.

The premise was straightforward enough - create a 20th century version of William the Conqueror's 900-year-old page-turner, the Domesday Book.

Instead of land rights and livestock, it would chronicle life in 1980s Britain, based on photographs and written accounts submitted by ordinary people.

It was an incredibly ambitious undertaking and, in many ways, the Domesday Project was a success.

The BBC received more than a million contributions and the electronic version was released commercially.

There was even a TV gameshow called Domesday Detectives, hosted by the doyen of 80's TV quizzes, Paul Coia.

But the system's designers were limited by the technology of the day.

Museum pieces

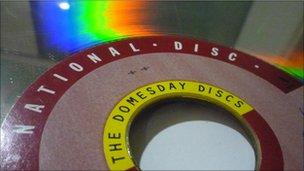

Domesday was released on two Laserdiscs - the cutting edge of video storage in a pre-CD, pre-DVD world.

Users needed a BBC Master computer running special software to access the Domesday interface.

The whole setup cost around £5,000 putting it out of the reach of ordinary people, as well as most schools and libraries.

Domesday used the now obsolete Laserdisc system

Only 1,000 Domesday systems were sold nationwide.

In the proceeding quarter century, the technology became obsolete, making the content on the discs inaccessible to all but a few enthusiasts.

Now, after a year of extracting, copying and indexing, the BBC is making the contents of the "community disc" - which details everyday life in Britain - available on the internet.

The team behind the project believe that they have finally been able to put right one of Domesday's great contradictions, namely that the fruits of this exercise in democracy were only available to a handful of people.

Domesday Reloaded producer Alex Mansfield explained that transferring the data from Laserdisc to the web was problematic because none of the data was stored in recognisable file formats.

"It was pre-digital photography, so all those pictures are analogue, even though they are on a Laserdisc. There is no compression," said Mr Mansfield.

Each individual photograph, satellite image or map page was stored as a single frame of video on the disc.

While the system appears to function like a modern-day website, with pictures loading when they are clicked on, the playback head is constantly jumping between 50,000 video stills.

Each of these images had to be digitised from the original one inch video tape.

Domesday's many written articles proved easier to recover because they were created in a digital format.

Although, with no data storage capability, the thousands of pages of text had to be encoded and stored on one of the Laserdisc's spare audio tracks.

The Domesday Project documented events like pit closures and the miners' strike. Excerpt from a promotional video with contributors and Project Editor Peter Armstrong.

Modern memories

In addition to making the entire community disc available online, the Reloaded project aims to continue Domesday's original mission.

21st century users are being encouraged to update the archive by adding their own photographs and written insights.

Through the website, contributors can upload new text entries and digital images.

Users can now access the Domesday Disk content through a standard web browser

Getting involved with Domesday in 2011 is much simpler than it was in the 1980s, according to Alex Mansfield.

"Everybody entered their data on floppy discs on a BBC micro in the classroom or library.

"They then took the disc out, put it in an envelope, put a stamp on it and sent it to the BBC," he said.

The revised Domesday archive will finally be closed to new contributions in November, at which time it will be handed over to The National Archives.

Future generations will be able to access this unique snapshot of life in Britain online for as long as the internet keeps working.